From the introduction-in-progress to my book-in-progress A Thing of Beauty: Reading the Romantics in a World on Fire. All photos by me.

–

A glittering blue day at the top of the world: Montenvers in the Alps above Chamonix, France. January 15, 2020. Elevation 6276 feet. Everything here is ice and rock and sky. Look up and there are mountains, jagged gray peaks from which wind whirls snow upward like smoke. Look down, and there’s the Mer de Glace, the million-year-old Sea of Ice, a glacier winding among the peaks, its surface rutted, its flanks gleaming turquoise-blue through swathes of grayish snow. Tiny dots move on that river: skiiers, finishing the ski route down “La Vallee Blanche,” a course that began at Aguille de Midi, about 12 miles away. Down there: that’s where we’re going, sixteen Midwestern college students and a young assistant, Ismail, and me. We zip coats, clutch notebooks, don sunglasses against the bright, warm glare. First there will be a cable car – little red-roofed glass pods, trundling on two wires through the void – and then a zigzag metal staircase, 500 steps bolted to the rock. Down, and down, onto the sea of ice. Somewhere, down there, a monster’s waiting too.

Two hundred and two years ago, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her not-yet-husband Percy Shelley climbed to this spot on mule-back. She was nineteen, he was twenty-five. “A vast river of ice,” she was later to write of it, “winding among the etherial mountains…” Yet at this point neither of them had written much worth speaking of, unlike the famous friend they’d followed from London to this place: Lord Byron, who’d fled England in the wake of a notorious divorce and sudden literary celebrity. On the shores of Lake Geneva, about an hour’s drive from Chamonix, they gathered (with some significant others) in Byron’s majestically gloomy rented house, the Villa Diodati, for bouts of drinking and tale-telling and competitive poeticizing that were heightened not just by their social cocktail of youth, brilliance, and instability but by the worst climate disaster Europe had seen in five hundred years.

In 1815, the year before Shelley, Mary, and Byron arrived in Geneva, the volcano Mt. Tambora had erupted in Indonesia, covering half the world with sun-choking clouds of ash. The sky went dark. Temperatures dropped. Harvests failed. Chinese peasants starved. So did Irish peasants. So did anyone without the resources to ride out food shortages. Europe became the cold, dark ground zero of a newly cold, dark world. 1816 was later to be named as the “year without a summer.” But at the time, it must have seemed as nameless and terrifying as any crisis, especially since it intensified an existing one: the Napoleonic Wars, when England and France, Wellington and Napoleon, had split Europe’s known world between them and ordinary soldiers and civilians were left to deal with the chaos in any way they could. On his way to Geneva, Byron stopped to tour the wreckage of the battlefield at Waterloo, where, like many Continental tourists of the time, he picked up souvenirs, including splinters of the Waterloo Elm (which had marked Wellington’s command post, becoming a sort of True Cross for veterans and vicarious warmongering) and human and equine skulls. Later that summer, he would write a poem called “Darkness” – “I had a dream,” it begins, “that was not all a dream” – that illustrates a post-apocalyptic nightmare of disease and cold and death. Later that summer, Mary Godwin would return to this spot in her imagination, on the page. It is across this sea of ice that the Creature comes striding “with more than usual speed” to debate with the man who made him, here on this glacier among the peaks that in 1816 were believed to be inhabited by demons. The girl still carrying, at that point, her mother’s name – Mary Wollstonecraft – and her father’s name – Godwin – wrote something for which “nightmare” is an inadequate word. From nightmares, you wake up. We haven’t wakened from Mary Shelley’s dream. We never will.

Inside the glass pods, my students and I clutch the rails and chatter nervously. Then the cables shudder and the cars start down. Above the rim of mountains, a sliver of blue sky narrows and sails up, away above our heads. Rock walls thicken at our backs and the light dims, even as the void before us opens, wondrous and terrifying. Borne downward and outward into nothing but air and rock and sky. No walls. The sun is dazzling. Do you dare to look. How can you not. This is what the Shelleys and Byron knew as the sublime, the stomach-clenching, brain-and-soul-electrifying tingle of being very nearly overwhelmed by the matter-of-factness of nature, its bigger-than-you-ness, its indifference. “Power dwells apart in its tranquillity,” Shelley wrote of this spot in his poem “Mont Blanc,” “remote, serene, and inaccessible.” Perhaps he could have scrambled onto the glacier’s surface – in 1816, it would still have reached up to the present lookout point, halfway up the valley’s sides – and looked down and around and up at what would have been the same sun-glare, the same untouched fields of snow around the same bare peaks of granite: “a desert,” he called them, “peopled by the storms alone.” The words come spontaneously to life in my own mouth now, lighting my own blood. That’s just what to call those blank untouchable plains, those curls of snow dashed by the wind into the air, right off the peaks, like smoke from a chimney-fire. Alone – he lands you on the word, at the end of the line and the stanza, on purpose.

The cable car ends at what used to be the glacier’s surface. Now the stairs continue down: relatively new, with twenty more steps added, supposedly, every year. They’re a relief, although they too are only metal over air: look through the mesh and see the rock slant away below your feet, shiny with snowmelt running down, water tumbling in fast little streams, right over the precipice as if it were no big deal. Focused on planting my feet and counting students ahead of me (please, God, don’t let anyone fall), I don’t notice exactly when the plaques start showing up, red letters on beige rectangles: Niveau de Glacier / Level of the Glacier 1985. Niveau de Glacier / Level of the Glacier 1990. As we descend, the dates go up. Without noticing, I pass from the twentieth century into the twenty-first. Suddenly, there’s 2015. That was the last time I was able to bring students to this place, when the train was running to this spot but the cable car was not, because of high winds. It is my own teaching, of course – packing myself and seventeen other people onto planes for what is now the fifth time – that is destroying the things I believe I am also celebrating and teaching to love. Venice. The Sistine Chapel. This glacier. The planet. Now it is 2020. And the steps – twenty more added, every year – are going down, deeper into paradox. As we descend, the dates climb closer to our present but the exposed surfaces of the glacier itself rise up to us from depths of time that grow deeper every year. The pearly blue surface of the ice – shy, dignified, naked – that is exposed to our eyes right now was never meant for us to see. And were it not for our own choices and habits and (dreaded word) conveniences, we never would.

Almost, now, as low as we can go. At least for now. And a cave’s mouth opens in the glacier itself. A blue astroturf carpet points the way in, covering cables of a generator: there must, after all, be light for us to see what we have made. The glacier’s surface is dirty, gray, lava-jagged; inside and underneath, though, it’s a cool deep electric blue. Remote. Alive. And we walk inside the glacier on a slight uphill grade, into a tunnel almost perfectly round, carved by who knows what machine, walls rippling and smooth from the touch of a thousand human hands and the subtle, subtle, subtle warming air.

Inside: intense presence, intense wordless paradox. It is blue in here, a dark that is not dark, a cold that is not cold. Other people are here, so are occasional electric lights and voices and from overhead some idiotically piped electro-mood music I remember from high school. The path leads in and around a loop and suddenly the entrance is out of sight. I’m in the heart of something massive that is also growing small, surrounded by the curved rippling walls of corridors that mimic veins in a beast of flesh and blood although no animal could survive here as anything but a limp trapped carcass lifted into light by the last hundred years of Anthropocene melt. It is dark in here. It’s not so dark. The ice glows with light and flickering spaces in which bits of rock or debris are visible but like water cannot be seen through more than three feet away. I have to be here to realize the gravity of what is happening, but my being here is the problem. My own breath is melting these walls right now. So is my touch. I can’t take my hand from a spot on the wall where a bit of what looks like brown moss floats suspended in ice that is melting even as I touch it. In five more seconds, maybe six, I will have brought that secret time-suspended thing, that silent innocent trace of who-knows-when past world, into the roaring mortal Anthropocene with me, the cause, the author and finisher of its undoing, the human stain. I lift my hand and turn my face away and weep. Students’ voices bob around me, our breaths lifting in vapor in the cold blue tunnel light. Water, we all are, all our mortal bodies, inside this glacier-beast that we have made mortal against its will. Water: the element at once of the present and deep time.

My assistant, Ismail, is silent. He’s a native of the Maldives, whose former president (currently speaker of the parliament) has staged underwater cabinet meetings to dramatize what will be the literal loss of his country to climate change. He’s twenty-four years old. Later he will tell me he’s thinking the same thing I am – his own body heat is melting the glacier – except he carries it to its logical conclusion: that water will make its way into the River Arve, splashing back down the mountain to Geneva, and thence into the oceans and higher and higher against the retaining walls of the capital city, Male, in which he grew up, where his parents and four of his six siblings and their friends still live, where as a rebellious teenager he smoked cigarettes and read history books and zoomed around the city on a motorbike, haunted and enchanted as any of us are by the soft sunset air of the beloved places in which we are simply and wordlessly glad to be alive. Later, he will tell me that before this trip he has tried not to think about what he and everyone in the Maldives knows is happening, the snuffing-out of the bright points of land and home in rising blue. My own grief, which I’ll share with him, is that my own childhood home – my literal and figurative inheritance, land in east Alabama – is slated by one measure to reach highs of 120 degrees for 60 days at a time in summers by the time I have told my family I plan to retire there, in twenty more years. “In one way or another,” the memorist Sarah Broom has reflected about the era of climate change, “we’re all living with an inheritance of soft ground.” Sinking, heating, rising, swamping, disappearing – it’s my Alabama, it’s Broom’s New Orleans, it’s Ismail’s Maldives, it’s the cool blue heart of the Sea of Ice that is now returning to the sea itself.

Wrecked and wordless, I scramble without knowing why for my journal to press a blank page to the ice – writ in water, John Keats’ gravestone reads, write in water, it commands – and two little pink-tipped white daisies tumble out of the spine. I picked them yesterday from the meadow next to Villa Diodati, where a fiery sunset like I’ve never seen lit up that most Gothic of haunts in Gothic, apocalyptic, glorious red. And now here these little flowers are, innocent riders-along from the upper world down into into the heart of this entirely different and equally blameless/innocent being. A glacier is a being. Beings die: Iceland held a funeral for a glacier last year. Innocent is not a sentimental world. My hand is on the ice. It burns. And I am walloped with a grief so intense I lean against the ice and howl, silent, face turned away to keep the students from seeing, although why shouldn’t they, this is the world we are foisting on them. My palm can’t come away. It burns. It should. Here in the heart of this great being, in its blue veined light, I repent, I rededicate, I grieve, and I recommit, all in an instant. If what I do in the upper world does not build a capacity for this, it is not worthy of my time or anyone’s. What is this? I can’t name it yet. I only know it’s real.

Eventually students and I gather in the dim underwater light and I read aloud the Creature’s plea to Victor Frankenstein: “Be calm! I entreat you to hear me before you give vent to your hatred on my devoted head. Have I not suffered enough, that you seek to increase my misery? Life, although it may only be an accumulation of anguish, is dear to me, and I will defend it. Remember, thou hast made me more powerful than thyself; my height is superior to thine, my joints more supple. But I will not be tempted to set myself in opposition to thee. I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.” We are feeling a lot of things here, I say, and I’ll not trespass on them. I’ll say only this: Here in the glacier’s heart, hear the plea from nonhuman to the human that made it. Duty. Justice. We ascend the 500 steps and then the cable car to the world above, tears drying behind my sunglasses. For another hour or so, I can’t say much of anything at all.

Two nights later, in the gorgeous sinking city of Venice – Lord Byron’s playground, setting for Childe Harold IV and Julian and Maddalo, and the death-city of Mary Shelley’s third child – one student goes right for the question. Here we are enjoying this incredible opportunity, she says, but it’s our plane ride, our consumption, that’s melting that glacier. Yet until I touched it I never got it. Climate change. I get it now. How do I live in this paradox? What do I do with my grief?

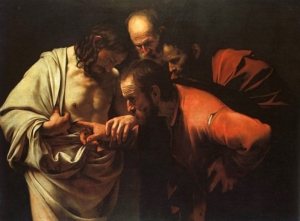

As much as a copout as this might at first seem, I respond, let me tell you a story. The disciple called Doubting Thomas – who we’ll see in a lot of artworks in Italy – could more accurately be translated as Touching Thomas. He has to put his hands on it, into the wounds, to be struck with the wonder and renewed loss half-salved that makes him cry out My Lord and My God to his beloved master who has suddently come back and will be gone again, ripping the wounds open in them both. The touch convinces him it’s real and gives him something to stand on, to go forward with, to live with. To touch is to know and to love and to find courage. Which makes him human Thomas. We need to use our bodies and our minds, all our human capacities, to feel and believe and know. We can’t act for or save what we don’t love, and what we don’t feel that sense of inner conviction and story and meaning about.

So how do we act, in this? First, admit the grief because you also bear the love and history from which it springs. Ours is a world that pathologizes emotion, hurries for a salve for any state of feeling beyond a social-media-ready rictus of cheer. Yet it is literally psychotic not to feel grief when faced with what we saw yesterday. Feeling strongly is not wrong, or inherently “problematic.” It’s a compass. It’s a map. It’s a guide and a means of truth, especially if it leads to questioning, and self-questioning.

Second, about that social media. Another student says she’s bewildered and saddened by the disconnect between sharing pictures of this trip and having friends and family see the same meaning she does. “These pictures mean a lot to me now,” she says, “and so do the words for these experiences even if I can’t get them right, and my mom just responds, ‘hey, great pix, smiley face.’” That’s the mismatch between medium and meaning that social media’s built on yet also tries its damndest to conceal from you – especially heartbreaking when the meaning is profoundly human and the medium is not. Maybe inhuman is the term to reach for: generated to spin corporate gold out of the straw of our desires and lonelinesses and ego-needs, to convert our own selves willingly into clicks. Data is the new oil, says Jaron Lanier. And oil – the unjust extraction, alienation, isolation, and creation of systems reliant on it – is what got us into this mess.

Social media and all its works are inherently inhuman. Identify and resist the anti-/inhuman – even though its very nature makes us unable to evaluate it and separate ourselves from it. And even though it is going to be hard, and annoying, and people like me telling you to do it will be annoying. Like giving up sugar or smoking. Harder but more important with every passing year. Because we will need all our human capacities, not to be numbed by the inhuman, for what’s coming. No one denies the internet is a useful tool. The problem is that it is becoming so much more than a way to check email, keep up with loved ones, or look up a course resource on the fly – it’s becoming a way of being, and of being conscious, in the world that subsumes and crowds out every other. “Technology has become the infrastructure for every aspect of our social world,” the founders of the Center for Humane Technology say on their podcast. “It is the now-genuine extension of how you wake up in the morning, how you go to bed at night, how you open your mouth to say something to someone. … The problem is that there’s a commercializing interest on intimate infrastructure that’s become the way you communicate. So now the very meaning of communication has a commercial interest. There’s no way basically for you to send a message from Person A to Person B without it being paid for by Person C, who has a commercial interest in what they want that context to be.” More than twenty years of college teaching has allowed me to watch that reality unfold in a population that has now (stay with me here) not only never not known the internet but never not known social media. And it isn’t good.

Third, find the thing you can do. Take nonviolent Extinction Rebellion protests; take this oped. For me, this is my mission, the thing I can do: keep alive memory, that most human thing. That is always what reading and being in the world have been about for me: keeping alive beloved and endangered things that may be forgotten and thus lost, but shouldn’t be, because there is something in them that can sustain us in our lives as good humans. A student pointed out that social media blows things up, then forgets about them. But books, paintings, buildings, and the spaces they build in our heads, hearts, and bones – those things remember.

Overall: we’ve got to build capacity. I’m still thinking of all this means, and will mean. But I’m committed to it. I looked students in eyes around that table in Venice and said: this past year, I realized that building your capacities is my mission in life, my professional reason for being. If my teaching doesn’t build your capacity for this future, then I’m not doing my job.

Building our capacities. This will mean each of us also has to challenge ourselves – including letting ourselves be challenged and touched by a variety of emotions, not all of which can/should be numbed out from, not all of which can/should feel good. Social media and infotainment only feel as if they build up your abilities – they actually erode the very things you’ll need to discover and build meaning, including meaningful contact with other people. Books and ideas and his/stories and experiences out in the world, with people and things that aren’t you or tailored in advance to you, can give you what I’m talking about. They can help you not be alone in your life and your own head. They can give you some gripping surfaces for your life in the world. They can help you grow into comfort with mystery, with complexity, with that which isn’t you or corporately tailored to you.

And that’s why I’m writing this book. To bring the Romantics, those great companions, alongside us in a time we need them to help us build our capacities for what’s coming next.

Read part two of the introduction draft here.

–

Thanks to Ismail Hamid for his companionship in this moment, for his excellent assistance on our January-term course, and his willingness to be a part of this blog post and the book-in-progress.