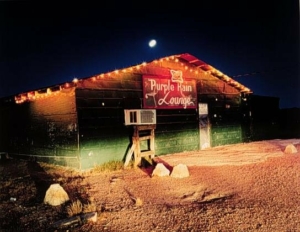

Madwoman: Alabama

In "Live from the Elks: An ArtHaus Anthology," 2023. (Image: "Purple Rain Lounge," Birney Imes, 1989).

The madwoman rattles around town in her filthy black car and nobody stands in her way. The car has fins and teeth, long and fanged as a crocodile – it’s a Cadillac, of course – except one bumper is torn off and dangling just above the street as if a dog had seized and fought it, snarling. We see her sometimes striding around to the trunk and popping it open. But somehow none of us are ever close enough to see what’s inside. Puffs of red road dust fly off when she slams it with the sort of heavy thud that means the trunk’s not empty. The underside of the lid is hitting something in there. A bundle of twigs for a broom. A roadkilled deer she’ll gut and drain for her dinner. The body – trussed and bound, eyes pleading up – of the last man who got too close. What we imagine is always worse than what is there.

Because men do approach her, and not always strangers, in the juke joint on the red-dirt country road just past the hanging tree and the graveyard with slave names scratched into the concrete slabs (HENRY died 1833) and the clapboard houses with their lush gardens of collard and okra and watermelon. There are warnings stenciled in black paint on the side of that cinderblock building with its door as narrow as a bad man’s mouth: NO GUN, HERE TO HAVE FUN. She parks the filthy black Cadillac at the end of the long line of cars tilted half-over in the ditch, one wheel down in the tangle of grass where the snakes curl, and she strides into the parking lot under the single sodium spotlight and slips through that door like a bad thought into someone’s mind. The men throwing knives under the light outside turn their heads to watch her go in. Nobody moves till she’s gone in and the door shuts behind her. Crazy girl back again, one of the young men volunteers, lifting his beer can from where it leaves a wet red ring in the dirt. One of the old men looks at him and shakes his head. That ain’t no girl.

What happens when she gets up in there is hard to say. Seeing her on the street of town – although it’s really just a wide place in the road now that the lumber mill’s gone and the Koreans seem to want to make their cars everywhere else in Alabama but here – you’d never think she’d draw a man. Skinny, scrawny even, with her skin so road-dust-ashy its in-between color is harder than it ought to be to name. Her hair’s patchy in places where the long hanks hang and her scalp shows through. Her eyes never meet yours or anyone’s and you’re afraid to look at her anyway so all of her is kind of a blur. Yet in that dark juke joint she sheds some kind of skin, eases and curls up next to some man on the bar stool till he doesn’t know what he’s feeling, only that it’s good. Her eyes are wide and inviting, her hair suddenly sprung out from its patchy dustiness in giant dark curls, long as moss from a tree, and softer. Whatever man touches her then feels one of those curls reach out to twine around his wrist and not let go. At first it’s only playing, like the pet garter snake he had when he was a boy. Lands, she laughs, I never heard such things before. But then she isn’t playing anymore, although when the game stopped the man would never, thereafter, know for sure.

The madwoman has been known to slip her shirt off and dance on the bar. The barmaid – who disapproves, as all the women do – reports a purple lace bra and skin that looks much younger than her face. The madwoman likes the old stuff best, the blues, all stomp and gutbucket and oh, baby, yeah, I’ll die. Sometimes the barmaid (who never tells the rest of us this part) thinks she sees the witch’s mark her oldest grandma talked about, the warts or veiny marks spread through the skin like rot, the nipples that turn, whenever you look at them, to eyes that blink and narrow in a sneer. You’re just afraid, they say. You stupid bitch. Behind your glasses and your keyring and your invoice pad. You’re just afraid to be like me.

The madwoman dances on the bar and all the men are watching, even the ones who know they shouldn’t. Those men will be the first ones through the doors of the church on Sunday and work themselves up to fling themselves out of the pew and down the aisle and holler help me Jesus, save me, help me right here, now. They’ll be first in line at the next baptizing down in the river, even if they’ve been baptized before, even if they’ve let the Lord take over for real, and they’ll look into the preacher’s eyes before he clamps his hand over their noses and bends them backwards, and they’ll plead silently help me. Save me. Please. Their wives and mamas looking on from the river bank, slapping mosquitoes and sliding a little in the mud, will smile. They won’t know what’s going on. But the little girl, the smallest one, holding to the pink-streaked rock she picked up at the water’s edge, will know. She’ll understand. Help my daddy, she’ll ask silently, inside her head. Help my daddy. He’s going down. She’s out there moving in the world. She’s out there in her car. There’s nowhere she can’t go.

It’s no use calling the police because they don’t know how to name the thing they’re looking at any more than the rest of us do. That hank of hair and piece of bone that fell out in the street one time – tied with a red ribbon – when the madwoman opened her car door looks like just a piece of trash to them. The scuffed place in the woods, with branches broken and the ground all clawed – just some bucks in rut, says the sheriff, scratching his big stomach, fightin like they do. The times she brushes against you on the sidewalk and looks into your eyes and snarls like a cat, and you wake up screaming every night for a week until your wife or husband soothes you down and leans against you and strokes you till you fall back asleep, repeating it isn’t real, it isn’t real. You keep repeating this although you know what you saw. What you see. That long black Cadillac cruising the back roads past your house and raising dust. The red lights getting smaller and smaller till the witch’s car is out of sight.

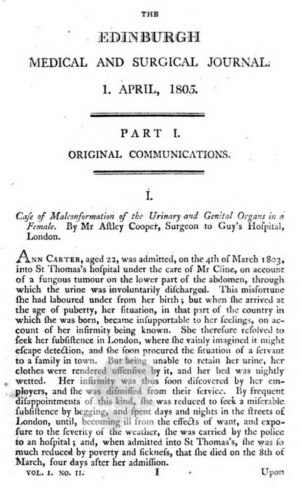

Malconformation: Ann Carter (1781?-1803)

Cutleaf (May 2023)

Based on the real-life, unknown woman in the medical history above.

Opening excerpt:

Along the dark street Ann hurries toward a place to hide. Another cold night is coming on here in the hinge between winter and spring, the first week of March although she’s lost track of the day. Beyond the wall of Parliament to her right, with cold bronze Cromwell on his horse, the Thames rushes past in its stinking bed. Frost rims the air like fur on a rich woman’s coat. A glitter of late snowflakes catches and swirls in the wind.

Between her legs the bale of sodden rag is cold. She carries it always: her curse, her shame, slung about her hips like a stillborn child bound to her as penace. To leak and leak, to run and run, to make her howl with pain when it’s touched. And, now, again, to lose her her place. “My God,” said Mrs. Macready last week in her velvet parlor, lifting her nose when Ann entered with the ash-bucket and broom. “What’s that horrid smell?” And Ann stood still, dumb as a mule, waiting for the eyes to land on her. They always did. And then Mrs. Pullen, the housekeeper, sat her down at the kitchen table, firm and dismally kind, the braids of onion and the chicken on its hook to be dinner that night for everyone in the house but her. “Oh, Ann, girl, the mistress says ye’ve got to go. Here’s a reference for ye, a good character. Ye’ve earned it.” There are so many things she can never say in this situation. Good thing Mrs. Macready can’t hear her guests calling her a jumped-up Scots merchant’s wife, getting above her station. Good thing character’s not of the body but of the soul. Because it’s my body, again. Isn’t it. The thing you can’t stand to see.

Ever since she left the village there’s been house after lady’s house, inn after inn after tavern with its pallet of straw in the back. And now, whatever hiding hole she can find. But there is always the body and the thing between its legs to haul from pillar to post, from doorway to bridge-arch to square of yellow light falling from window through which she can see the normal people drinking, eating, warming themselves, sitting still for as long as they like. Like a dumb child that’s the cause of shame yet unknowing of wrong, her body begs her: What’d I do to be so hungry, so wet and raw? So cold? Oh, why am I not fit to look upon?

The weight of rags around her hips is familiar now. Even the chafe of the reddened skin is known. She’d bathed the thing between her legs when she was in work at Mrs. Macready’s and could haul a kettle up to the garret she shared with the other maids. “Oh, Ann,” jested Irish Bridget, “don’t ye find it a trial to bath so often?” But then Bridget saw her legs, and the thing between them, and went white, even crossed herself. “Oh, Ann. I’ll pray for ye.”

“Yes, well,” Ann said. That was the third house in a year or maybe fourth and she was tired of prayers. “It ain’t exactly suited God to take this from me, has it?”

All those Christians. Comfort the afflicted. That’s what they are taught.

Here it is now, the great arch of Westminster. On nights like this all the hiding holes are full. The crevices up under Blackfriars and London Bridge and Westminster Bridge as well, the broken-open cellar near the Swan and Hoop where the fire started and has never been repaired, the lean-tos behind the breweries, where you can find old wicked Sal and all the rest, sucking on the barrel-dregs. The word’s got out among them that Lord Mayor’s decreed the Abbey door be opened on such nights. “Tell us another,” says Ann. “Every time I’ve tried it’s locked. And anyway, who’d let us in?” With all that gold, and all the famous tombs. All that splendor and illustriousness. Against old wicked Sal, and Will, and Mary Jane, and her. But even if the door isn’t open there will be the arch, the nooks in all the walls. Some place to get out of the wind at least. A hole for her against the river and the stars and all this city.

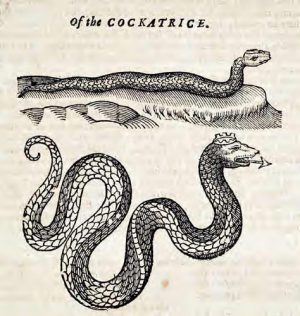

The Serpent

“The Serpent,” in The Hopper (Summer 2018), Issue III * Nominated for a Pushcart Prize

Genesis / Proverbs 31

He left her alone in what used to be their garden, with blackberry brambles clotting the fencerows and all the animals bawling to be fed. All winter he’d drunk and raged and watched her. She’d spent whole days hunkered there next to his sleeping couch, her hand limp in his fists. The jars on the pantry shelves and the smokehouse hams diminished: three, then two, then one. When February dawned, bright and cold, he wobbled away down the red dirt road with his knapsack on his back, his clay-colored hair bristling. You’ll never survive here without me, he shouted back at her. Every move you make will be in pain. Never, once, could she have dreamed that she’d be glad to see him go. But left alone, she could put the garden back the way it was.

So she took stock. The tin roof on the house: still good. The well still drew;the fig tree and the plum and peach trees were setting bloom and leaf. The vegetable patch, however, had that sunken, scraggly look a garden gets when a woman has her mind on something else. Rickety wooden winter-bleached tomato frames still cradled brittle white vines, where a few cold-leathered orange fruits still clung. Blue-gray collards burst up into yellow flower. Pepper plants were smashed flat where some creature had rummaged through. A possum had laid waste one last melon over by the fence, its striped hull cracked and teeth-raked, its faded heart laid bare. At least the deer fence, ten feet high, was still intact. The metal discs he had cut for scaring still shimmered and bounced in the wind. An evil little face was etched into each one; they’d done that together, laughing, charming a protection for their food against the crows and deer and dangers threatening this garden that would surely feed them both together for all time.

Without him, the milk cow lost a tendency to kick. The chickens clustered back around the house. The big yellow cat came out from under the porch. She replanted the seeds, upright in their twists of brown paper. Ole Timey Blue. Cow Horn. Cherokee Purple. Trail of Tears. Arkansas Traveler. Mortgage Lifter. Hill Country Red. Yellow Gold. Moon and Stars. She ripped out the old tomato vines and the tall fierce weeds and hauled them to the place where the other garden skeletons were melting down to next year’s food. She stropped the razor and sharpened the scythe and swung it through the high grass to cut it all around the house, the garden, the fig tree. Because in the warm weather coming on, snakes would be moving.

He had hated snakes beyond reason, ever since he opened the chicken coop and found a brown-and-gold rat snake stretching its mouth open around a fresh white egg. Don’t bother them and they won’t bother you, she’d argued. They keep the mice away. She’d stopped up every hole in the coop and reburied the fence wire and thought that was the end of it.But in his bad time, as the grass feathered high and the garden grew wild and then withered and the chickens got feral and experienced, she came to fear what might be out there: the panicked muscle writhing to life under her foot, the hot needle to her calf. Overgrown and wild and forlorn, this was not the happy garden they’d been given anymore. She’d die out here, no one to bury or to mourn.

But now, on a summer morning, the first tomato-ripening heat just taking hold, she lets herself release those fears. The garden is hers again. The seeds are up and flourishing. The melon-hills are crowned with glory, the beans climbing their cornstalks right on time. Green baby crabgrass bristles between the new collards and the lettuces. If she lets crabgrass go, she’s in for a war, gripping giant clumps of it and heaving it out. Gripping is a problem for her now. At night her hands ache, down in the joints. So big-knuckled and rough they are, so different from the slender fingers she held up before her own eyes as a girl, marveling This is my body, all of this is me. Deep in her hip is a grinding of bone on bone that freezes her in place, howling, if she catches it wrong. So she stretches and she takes a rest and she tries to ignore the way her body is no longer fully hers. Traitorous and tired, it’s been swelled and split by both her sons. The one son’s dead. The other—she doesn’t know where he is. It’s a pain worse than her swollen hands to think on them. So she chooses the pain that feeds her. She rubs the pig fat against her joints at night to keep them as supple as they can be for the next day in the garden. For a woman, keeping herself fed in this world is a full-time job. And now there’s only her, out here at the end of the world, to see to it.

She chops the young crabgrass with her hoe, turning the roots over to bake in the sun. Then something rustles in the squash vines, slow, low against the ground. She freezes. There’s only one thing that sound can be. But she can’t just back away or it’ll find her sometime she’s less ready for it, like when she’s barefoot on the porch steps, walking out into the yard at night to see the stars. This is her garden. She has to be free to move in it.

She steps back and slams the hoe into the soil. I tell you to come out. The air thickens with a heavy liquid hush of skin on skin. She chops the dirt. Come out. Slowly a rattlesnake unfurls itself into the light. Black birdwing shapes on its back, bird after bird after bird, loop toward her in the dirt. Its thick midsection is as wide as her right arm. Its black tail ends in a long cluster of rattle-beads. Its head is as big as her own outstretched hand, fingertip to wrist. And its lidless eyes are open, watching her.

Cold fear shoots down her spine, locking her to the dirt. Words scramble in her head: be still, it’ll strike, oh why oh why did— She stares at the flat spade-shaped head and marshals her lost man’s counseling words: big snake is less to be feared than a small one, big snake knows what to use his venom on, little snake’s just like a shirttail boy, lash out at anything he can. Wild shirttail boy. Lost son. So much fear and grief now all undone in her. Why, oh, why did she command this beast out into the light?

The black eyes watch her. Snake venom takes away the joint pain. Whose voice is this? Sure it does. Longing rises in her chest, coloring the fear like wine in water. No more pain. Dizzily she pictures it. Step forward. Grasp this rope of muscle around its throat. Slip her right hand underneath the belly scales—it will be heavy—and lift it toward her heart. The flat eyes stare through her at nothing. I’ll be still. Where is that voice coming from? You’ll pick me up and I’ll be quick. Just one little bite. You won’t hardly feel it. And all your pain will then be gone.

Inside a pure cold emptiness opens, waiting, humming like her lost sons in their sleep. It is the place from which fear reaches for her in the night. The space in which her thoughts chased around and around as her lost man gripped her hand between his own. It is not-knowing. It is intolerable. It is inescapable. It is where she must live now, on her own. She cannot run. And the doing and the caretaking of each day—the clothespins on the line, the sharp edge of the blade against the dirt,and the red skin of the fruit her own hands have brought forth—is the sturdy warm force that sends the fear back into its hole.

She lifts the blade and swings it down. The big snake bunches backward in a self-protective coil, rattle-buzz slicing the air. It’s not a hiss, it’s a harder sound, silver-edged and mean. Mean? Afraid. All down its neck is a split in the black-and-tan scales her blade has opened. It’s bleeding. It is red meat and nerve and hunger. Just like any other thing.

She steps back and the rattlesnake whips away under the wide sunlit leaves. The fence quivers as it hits what must be a hidden hole, back there, in the wire. It’s out in the pasture now, seedheads swaying as it passes. With her hoe upright in her hand, she stands and watches it. Rustle, rustle, away and out of sight.

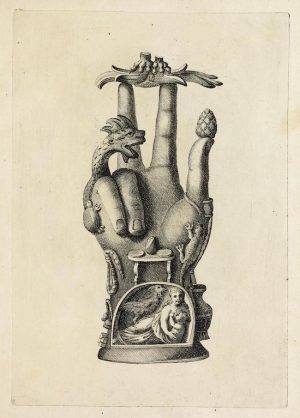

Wrestling the Angel

“Wrestling the Angel” from Inch (Bull City Press, Spring 2015), Issue 28

Genesis 32:22-32

He woke up when it smacked him with its wing and rolled him down the hill until he fetched up in the stream. Son of a bitch, he sputtered. What the—

He turned his head and there it was, smiling at him. How had he known it was a wing that hit him? No wings here that he could see. This was nothing but a man, big-legged, spraddle-footed, in a thick gray tunic like you’d cut out of two prison blankets and lash together with a string. No belt. Toes in the dirt and big arms folded and that smile.

He lunged up and bulleted his head straight into the gray-wool-coated ribs. The arms snapped around his neck and squeezed. He choked and the air around his eyes went red. Goddammit, he gasped. His legs wheeled in the dirt and one heel caught and he pushed up and got his elbow in the gut. Oof. It was a man after all: he felt the cushion of the muscle rip and swell as he worked his fingers in, his teeth. He’d go for the eyes if he could, but the big arms had his head tight, still twisting.

He shoved backward and straightened up and looked. The man stood there, grinning. And something stilled him. He’d heard the stories. Something like this didn’t come to you without there was a reason.Angel wasn’t quite the word – that was for some fragile thing, all robes and feathers, that only the oldest folks had seen. This was some bandit man, some murderer. But yet – that gray robe, still unstained. The clear eyes, the shining skin. That mocking smile. There was no blood. You had to try real hard and not let a creature like this go, if it came to you. You had to hang on. You had to try to be a man.

He hurled himself at those big red-dirt-dusted feet and tried to drop the angel – angel?—that way, but suddenly those feet were gone, slipped right upward out of his grasp like a girl’s hand leaving his in the dark. I will not let you go, he muttered. Then he was crying, so damn angry he could hardly breathe. You bastard, he sobbed, you get back here. I need a blessing. I’m not gonna let you go.