Easter Sunday, 2019. Westminster Abbey and Parliament Square. Extinction Rebellion and Brexit and Eucharist. Two hundred years on from Shelley’s “Mask of Anarchy” and Keats’ Odes.

What if this is the site of Incarnation, here and now?

parliament square easter sunday

Carn, the root: meat, flesh. Incarnation: the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. The Word, the ultimate verb, is the divine voice speaking life into and making happen. It’s also the lever we wield to shift something in our present moments right now. I love you. I wonder if – Say it now because there is no other time than this.

I ate the day / deliberately, writes Seamus Heaney, that its tang / might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

“This is the day that the Lord has made,” speaks the priest. His words rise to the ceiling on this bright Easter morning that settles gently on thousands of others like soft linens stacked in a chest; the deepest ones settle deeper still, unraveling and softening, receding into an unknowable dark. “Let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

Be glad in it. Be present. Be among the hands in every shade of brown and beige and pink lifted to receive. It takes some time. The Abbey is entirely full. The line for entrance stretched all the way around the block. But that’s all right. It takes as long as it takes. The choir sings a Taverner motet, voices rising and twining in the sunbeams etched in incense-dust. When the Sabbath was over Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James and Salome bought spices so that they might come and anoint Jesus. Alleluia! And very early on the first day of the week they came to the tomb when the sun had risen, so they might come and anoint Jesus. Alleluia!

They were early. They were prepared. We celebrate, now, what they did not find.

Relationships to time can enslave or free people and societies and millions of nonhuman creatures who never look at clocks. Take our favorite words, convenience and efficiency. Following Hannah Arendt, I’ve written that efficiency – especially as preached and engineered by the corporate infotainment complex beamed at us from screens in Piccadilly Circus and our pockets – has the potential to be a totalitarian force. It knows one value: conversion of anything, no matter what, into ones and zeroes and dollar signs. What cannot be converted is not valued and, therefore, according to “efficiency’s” pernicious gospel, not worth saving.

Therefore, to assert the pricelessness of our planet, which our drive for “efficiency” is actively destroying, you create inefficiency and inconvenience. You come in peace. But you rupture the flow of business as usual, bucking the tide of habitual time to crack open a reflective space in life, a space in which you can see what’s really going on. This is the logic of worship. It is the logic of meditation. It is the logic of the creation of art or the decision to put your phone away when you’re with actual people you say you love. It’s the logic of nonviolent protest. Put your body here, right here, at the lunch counter, dressed in a jacket and tie. Stick up like a rock in the flow of time so that the rest of us, caught up in it, have to stop and look and double back and look again, and think again, about what we are actually looking at.

This is the logic of Extinction Rebellion, the movement unfolding here in London in these weeks. It’s blocked bridges and disrupted Underground lines and camped in Parliament Square. It’s drawn every response from scorn (the Daily Mail: ECO PLOT TO RUIN EASTER) to understanding (yes, we are out of time, and no, the governments, plural, are not listening, and how else can we get their attention?) to a mixture of both from people worried about the planet and worried how they’ll get to work on time so they can keep clinging to the precarious security (too scary even for me to add the scare quotes that in the twenty-first century do belong around that word) that those of us under 45 in particular are scrapping for and were promised if we were good and did our work and now just don’t seem to be finding, no matter how hard we work. At some point, without any of us really noticing, the door between us and a Prosperous Future began swinging shut, its hinges rusting in place at each new stage. Humans aren’t the only victims, of course: we’re just the only ones that can trace this state of things back to our own decisions. We know there are too many of us. We know we buy too much plastic stuff. We know that hard choices must be made and will change things including our own daily lives, which is where we balk: do we really have to go that far? We know that future generations are behind us in this line, trying to squeeze through that door too. What will oil those hinges so we can nudge that door back open now?

One row in front of me, a white-haired woman waits to receive the Eucharist. CHRISTIAN CLIMATE ACTIVIST and the Extinction Rebellion logo, the X-marked hourglass, float in white on the back of her black sweatshirt. She stands for the hymns, then lowers herself into her seat again with both hands. She receives. At the end of the service she shoulders her backpack and sleeping roll and walks with the rest of us back into the world. So many of the Extinction Rebellion protesters are elderly people, carrying signs that say things like I’m Here For My Grandchildren. Or the one I can’t forget: Where is Our Wisdom?

Parliament Square is alive with voices and laughter and the blip, blip of police vans coming through. Priests stand in the churchyard under the stone carvings of Oscar Romero and Martin Luther King on the Abbey’s east face, smiling and shaking hands. The crowd is huge. The mood is jubilant, Easter Festival Day and something more. Right beyond the gates, an Extinction Rebellion tent camp blocks the street. The air is alive with a chorus of bells from the great tower. Overwhelming and joyous, it goes on and on and on. Leaning on the fence, I lose myself. When I turn around, a protestor is being loaded into a police van, right in front of me. She’s limp, obedient to the code of nonviolent civil disobedience: put your body there as a resisting weight. The police are gentle. The bells chorus on and on. I see only a spill of graying brown hair like my own, a fleshy pale underarm. “Is she sick?” someone asks. No. Like the gray-haired man in spectacles who’s already sitting quietly inside the van, seatbelt buckled, she’s being arrested on purpose. The police are gentle, doing their job. According to the ads that cycled through the Underground this spring, their starting salaries are thirty thousand pounds a year. I remember the good policewoman (in manner much like brilliant Sarah Lancashire on “Happy Valley”) who helped me and my students once, and I remember her name. Like teachers, cops are now among the public servants whose jobs – but not their resources – keep stretching to include what used to be someone else’s brief. Mental health. Hunger and homelessness. Frustration at governments who say they’re listening.

The fewer resources you have, the more inconvenienced you will be by what comes next.

Last Sunday, we Methodists blocked some traffic too. From John Wesley’s little church on City Road, we set out in a loop around the block to celebrate Palm Sunday, waving palm crosses and singing hymns. At the head of the line was a donkey named Danny, shaggy-coated and soft-nosed. We had a donkey like this named Jenny once, companion of imaginary treks into the woods and down to the creek, big enough for even a six-year-old to climb up on by herself. When Jesus comes into the city, he sends someone ahead to get a “colt” he knows is tied there for him to ride on. In some translations and in tradition this has become a donkey, foreshadowing a long symbolism of stubborn humility and sly reversal. Cosimo de Medici, the Warren Buffett of the Renaissance, rode a mule. In Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston grants mean Matt Bonner’s yellow mule a heavenly resurrection where he’s the one behind the plow, and Matt Bonner is the one in front. Before the Emperor Constantine decided otherwise, the Romans thought Christians (or the “Jesus Movement,” as they are perhaps more accurately called) were losers: why would anybody worship a god who’d taken human form on purpose and then to compound the insult let himself be arrested and put to death in the most humiliating and criminal way? But of course, says the Jesus Movement, that’s the point. Ever since, empire has understood either not at all or a little bit too well how stubborn Jesus is, and what kinds of stubbornness He inspires. He’s the descendant, after all, of old trickster Jacob, the big-talking wrestler, latching on to that angel and hollering I will not let you go until you bless me.

Following Danny the donkey and the adoring children around him, we toted our banners and big wooden cross and little handheld palm-frond crosses across City Road into Bunhill Fields, the Nonconformist cemetery. Susannah Wesley and John Bunyan and Daniel Defoe and William Blake are buried there, among daffodils and bluebells and blossoming trees. Congregation members in high-vis vests sprinted ahead to wave down traffic. Bus drivers and pedestrians looked on with bemusement or recognition. We went on, singing. At Islington High Street a burbling of music joined us, a jaunty melody playing from an RV labeled The Mitzvah Tank: Your Source for Everything Jewish. Can you make this up? Nope, not in London. Turning for home, we crossed in front of the Old Street tube station, donkeys and preachers and banners and cross and elders and children and all. A rich young ruler – I mean, some dude in a BMW – began to honk. “Sonofabitch,” I muttered. (Yes, this is why I need to go to church.) Guess we’re inconvenient.

And in the Underground, on the way to see some art, I saw a tree of life. It’s a cherry tree, they told me, going home to be planted.

The British sculptor Henry Moore served in World War I as a bayonet instructor: no wonder, as Geoff Dyer has written, that he became known for exploring the possibilities of the human body, and the hole.

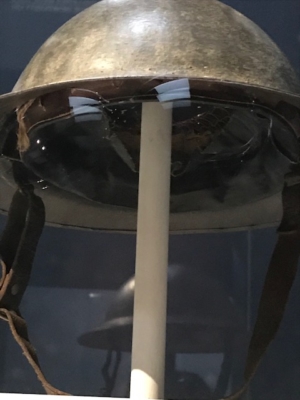

At the Wallace Collection, a brilliant exhibition pairs Moore’s “Helmet Heads” series with the actual medieval and Renaissance helmets that fascinated Moore when he came here, as an art student, to draw them. Look at his sculptures and you see the way that art deliberately interrupts space and rebuilds that space around itself. Moore makes helmets that are also heads, with delicate shapes inside that could be spinal cords or cerebella or even consciousness. In metal and in the spaces that metal surrounds but does not contain, he has made something that did not exist before. Something that looks like helmets and like the fragile skulls – and unknown worlds within – that we hope those helmets will protect. (The holes in the “Helmet Heads,” borrowed, as the exhibition suggests, from the ventilation holes in German helmets, suggest that hope and its precariousness in a heartbreaking way.) Protection always also acknowledges the fragility of what you hope to protect. The world gets through.

And change begins inside that space: the stubborn and delicate mind.

Protect our fragile earth, prays the priest. Your fragile creation.

Surrounded by Westminster Abbey’s bells two women walk forward carrying a giant red banner that pleads for this too. It uses the words wonder and fragile and miraculous. They are pleading, with anyone who will listen. Protect.

To love the fragile and endangered thing you have to see it clear. What better time than now. What better season than this, as lilacs froth over garden walls and train-line barriers and people flock to any available patch of grass to lounge and picnic and tilt their faces to the sky and even curl up in one another’s arms and fall asleep.

This is what the women did at Jesus’ tomb: they slipped up there in grief, with armloads of fresh linens, to get the body of their beloved criminal and treat it properly, according to the habits dignified as custom, like the rebel Antigone with her brother’s body. And they did not find what they expected to be there.

Tears in your eyes: let them come. It is spirit, looking for a place to land.

What will we find if we look, right now?

What if the Incarnation is right here? Waiting to be seen?