“[We must think of fungi] not as a thing but as a process: an exploratory, irregular tendency.” – Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures

Fungi burst borders and boundaries. Of matter, of thought, of mental categories. They tendril between previously discrete things and knit them together in a web of life that is always becoming, always questing outward, downward, and sideways in 360 directions of curious, businesslike survival. They made it possible for single-celled organisms to develop into plants by showing them how to make roots. And this week – in one of the sudden flushes of growth they’re famous for, strong enough to lift asphalt and crack rock – they knit me a whole new set of fresh ideas about teaching, writing, and mentoring students in a world where building capacities for curiosity, resilience, and joy matters more than ever.

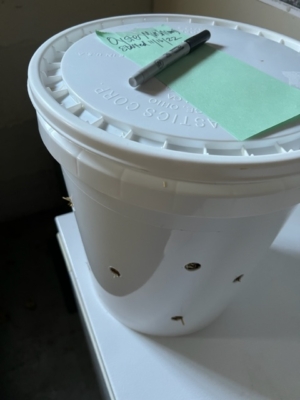

Thursday night, I traveled through a blustery wind to the warm basement of the public library, where about twenty community members had come to learn how to grow mushrooms in a bucket. Luther alum, farmer, and high school biology teacher Adam Bohach hauled out supplies: bags of spawn (a born teacher of adolescents, he could repeat this word without cracking a smile) and old pillowcases full of straw he’d sterilized by soaking them in barrels of water mixed with pickling salt (still bearing traces of ice from the sudden freeze we’ve just had). He taught us the basic microbiology involved: with our buckets, we’re replicating the trunk of a tree, where a mycelial body can feed on the interior matter and then flower toward the light through cracks in the bark. Sterilizing the straw with the salt water helped kill off organisms that could outcompete the oyster spawn inside the bucket: “and oysters are good for beginners,” he said, “because they’re aggressive. Shiitakes are slow, take more practice.” And then we set to work. With a drill, we made holes in the bucket, then rubbed the whole bucket, inside and out, with alcohol and donned gloves and a mask “to protect the mushrooms,” Adam explained, “from us.” With a layer of straw in the bottom, we were ready to gather a small chunk of spawn from the specialized bags and sprinkle it over the straw. Pale brown and crumbly, a mix of mushroom spores and specially prepared growing matter, it smelled sweet and earthy, with a savory tang. Another layer of straw went on top, packed down to ease the mycelial growth: “even a centimeter between one piece of straw and another,” Adam explained, “is like Decorah to LA for a cell. You want to reduce that distance.” And we continued all the way to the top in alternating layers, then put the lid on and sealed it down tight. Now each bucket is ready to become a harbor for a mycelial network that should fruit in a few weeks, then again, in two or three flushes (cycles of mushroom growth) until the mushrooms slow and stop and you can empty the straw as compost into your garden. (Worms love it, Adam notes – which made me wonder if it’s time to bring back my vermicomposting bin.) You can mist the holes to mimic rain as the mushrooms begin to appear, but mostly you can let them be to do their own thing in the dark.

(The video below, from Merlin Sheldrake’s website, is “Oyster mushrooms sprouting from a copy of Entangled Life with song by Cosmo Sheldrake. All sounds apart from voice and double bass are recordings of the fungus devouring the book (more info).”

Until I found myself excitedly describing this process two days later to a student who is developing an original manuscript over the course of a year – and the patience to keep writing, exploring, sitting with it, writing some more, letting it tell him what it is trying to be – I didn’t realize how deeply mycelia as metaphor and structure of thinking had grown in me. It helped that I had been listening to Merlin Sheldrake’s wonderful Entangled Life walking to and from school – a book worth buying to read and underline as well as hear. Now I remembered my childhood fascination with fungi: the giant shelves of spongy rosy golden-brown flesh I’d haul down from the woods and into my junior-high science fair to display on paper plates; the humming, patient, not-quite-animal presence they seemed to emanate, so like what I’d later name with Wordsworth’s line “There is a spirit in the woods;” my constant desire, only barely suppressed, to break off a crumb from their leathery frilled edge and take a bite. And as I cooked mushrooms and peppers and onions and melted down a pumpkin into sweet golden pudding in my own kitchen last night, cold wind howling outside, I was stopped by Sheldrake telling an anecdote: when Haddon Hall in Derbyshire was renovated, a fruiting fungal body was found in an oven that was then traced all the way back to – and helped the owners to detect – a case of dry rot in a room some distance away. That anecdote was there when I sat down this morning to write a scene for my next novel – and the network of stubborn, gentle, nameless life, the constant growth-ward and 360-exploring tendency, that mycelia embody has become a structural engine for the whole evolving book. (Thank you, Merlin Sheldrake!!) If reading, thinking, dreaming, notetaking, walking, and all the invisible idea-growings writers do are the mycelial body, then the words on the page are the fruit – which may, once readers pick them up, seed themselves anywhere.

But even more, mushrooms – and the place I stand on the shore of all the learning I want to do, all the geeking-out any teacher and any human must never stop being able to do – are turning me back toward my deepest mission: living more fully in this world as it is and might be, and helping students build their own capacites to do the same.

Recently in my first-year course, Paideia, we’ve been reading together George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four and the graphic edition of Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny, with Nora Krug’s wonderful designs enriching both. Students were struck by how Big Brother creates a climate of paranoia and fear by turning people against themselves, and against the mycelial-spore of self deep inside each of us that it’s Big Brother’s ultimate goal to hunt down and eradicate. “In principle a Party member had no spare time, and was never alone except in bed,” Orwell writes.” It was assumed that when he was not working, eating or sleeping he would be taking part in some kind of communal recreation: to do anything that suggested a taste for solitude, even to go for a walk by yourself, was always slightly dangerous. There was a word for it in Newspeak: ownlife, it was called, meaning individualism and eccentricity.” In Sheldrake’s terms, ownlife is also the growing space for entangled life — the deep network of questions about and relationships with human and nonhuman others that teaches, feeds, corrects, draws out, and creates our own selves and ideas and words and dreams every day. Anything that expresses this entanglement is a crime. “So,” I asked, “what’s your favorite crime? And why, in this novel, is it something Big Brother will get you for?” Students dug deeply and brilliantly into the idea that curiosity, sensuality, wonder, joy, geeking out, privacy for pondering and not-being-responsible-to-anyone, love — all those outward-questing, 360-degree-radiating tendencies that fall under the heading of pleasure — are such a threat to Big Brother because they build a self that is entangled with the 360-degree-radiating, outward-questing tendencies of all of life in the world. In the novel, a fictional Asian version of Big Brother is called by a name that means “death cult.” To isolate the self and focus it only on the central figure of Big Brother, to un-entangle it, is to kill it. To deny multiplicity, beauty, everything not reducible to a singularity and an “efficiency” – this is to deny the very nature and reality of biological and spiritual life itself. It is, at every level, to die.

In a time when rebukes to cults of aridity and death are springing up, even on the verge of another savage and dizzying season of climate change, mycelia as metaphor and fact are teaching me new, matter-of-fact routes and pathways of hope. Election-denying and conspiracies (and the notion that we can’t “afford” support for Ukraine) were rebuked across America on Nov. 8, as a “red wave” was more like a pink trickle. Crypto-currency (“yield-farming all the way down,” with no actual roots that build anything) and Twitter (revealed, with $7.99 authenticity stamps and dumpster-fire “management,” as the fake community it always was) are collapsing. (Surprise, surprise!) I hope and pray we are learning anew to ask that vital question: “Is it life-giving or death-dealing?” Hope lies in growing, doing, reaching out, putting your body in the new place and letting it feed you. Work with what you have. Keep questing. Entangle your life, and your art, with the world.