This is the book – and this is the writer – to whom I owe everything.

When did The Giant, O’Brien cross my path? Sometime around my transition from 20th c. MA to 21st c. Ph.D student, when I was devising scholarly research topics and writing and publishing short stories on the side and groping my way toward the question I now talk about with my own students all the time: what do I actually think, what do I actually know, and what do I actually want to say? Romantic women’s writing, Southern literature – those had been real interests of mine since my undergraduate days. But I pursued them, I see now, into graduate school with a bit of hesitancy: what do I really want to say about these things? Not sure I can tell you. Where’s the intrigue, the weirdness, the spark I have learned to trust and follow when writing fiction? Not sure I can tell you that either. And anyway, is scholarship supposed to have that spark? I wasn’t sure. In a variety of ways, I was absorbing the perhaps-inadvertent but always-unfortunate message from my professional elders that intellectual seriousness and sparkiness, fervor, hunches, geeker-outery, and just-because-it’s-cool-ness are not compatible. Creative writing and literary study are not compatible – especially since creative writers just make stuff up, really, while scholars work systematically. Right?

But when I read The Giant, O’Brien, I felt – Frankenstein’s-creature-style – a jolt of electricity, a pure thrill, jump between the creative and scholarly hemispheres of my brain. Here was a lean, nervy novel based on real figures from the past that felt alive – so much more than the increasingly labored twentieth-century-Southern-set fiction I was wresting from my own experience. Here was John Hunter, a surgeon like my own father (but more extreme), who transformed medicine by transgressing the boundaries between discovery and crime. Here was a vivid, scrappy cast of imagined eighteenth-century urbanites. And here at the center was another real man: Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant, courtly and melancholy and ill at ease, whose bones rustle and crackle like growing trees, whose bones – I couldn’t have known then – I’d look upon with my own students as we stood in London’s Hunterian Museum, more than ten years later. Then and now, he and his world are illuminated by the light of Hilary Mantel’s prose: faintly greenish-whitish, like the light of a cold moon, mercilessly clear, and yet, in that clarity and lack of sentimentality, eternal.

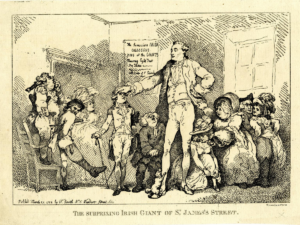

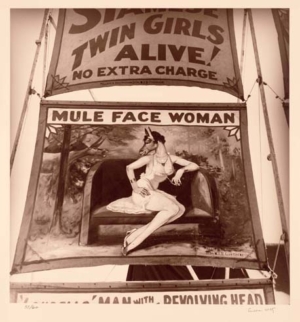

When Charles Byrne entered my dissertation, the whole project came to life – particularly deep in my brain where Mary Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Frankenstein’s Creature had already taken up residence, where the novel I didn’t know I’d someday write was perhaps stirring. I had been writing diligently, albeit with real interest, about the figure of the woman intellectual in the late eighteenth century, the bookish girl considered odd and distasteful by much of the world around her (where could I have gotten that idea?) But Charles Byrne (via Hilary Mantel) gave me a new, charged, endlessly rich and troubling word: the freak. In political cartoons and public discourse of that time, anomalously bodied individuals (to give them another name) stood in for all kinds of social anxieties. Daniel Lambert (1770-1809), the 700-pound Leicester farmer, became proof of British strength against a tiny Napoleon. Caroline Crachami, “the Sicilian Dwarf” (1815-1824), became an exaggerated model of delicacy and femininity to be fawned over as she stood on a table, surrounded by male journalists. “Monstrosity” – the term “monster” was used as a relatively neutral medical term by Percy Shelley’s doctor, William Lawrence – was used satirically as well to “normal” people who “deformed” their bodies with fashion, fads, or – in the case of bluestocking women – too much reading. As Paul Youngquist reminds us, this was indeed an elastic category: Lord Byron, caricatured and scrutinized and adored as a Regency celebrity, walked with a limp and wore a painful corrective boot as a child.

At my dissertation defense, my bemused professors remarked on the interesting bits of information they’d learned from Chapter Two, on women and other anomalous bodies, in particular (they also liked the stuff about Mary Wollstonecraft and corsets in Ch. 1). “This reads like a collection of short stories,” they said. “Thank you!” I beamed. Even at the time, I realized that in scholarly terms, this wasn’t quite a compliment. But down in the brainstem-base where fiction’s best impulses lived, I rejoiced, because I knew that somehow I’d come back to this material. Now – in novels and in my next nonfiction book – I am.

So what can I (and more importantly, my students) learn from all this – and Hilary Mantel?

* Greater distance between you and your subject can impel an imaginative leap that brings your writing alive – especially if it leads you to learn something new. In my Advanced Fiction textbook, I write about “psychic distance,” the place you have to “stand” in relation to your characters to be able to imagine them as characters, not merely as projections of yourself. This may require research to root them in their world with what you also share: the common language of the senses, of the human body. Then you can ventriloquize and imagine any character as a distinct character, as Mantel does here with John Hunter himself, moving from third person in Ch. 2…

Scotland, day: the child is alone in the field, the black ruts rising around him: flat on his belly on the damp ground, a vast sky swirling. His chin is on the earth, his body is blue in bits, where he has got his clothes wrong. It is his own task to dress himself, cover himself decently, and if he’s cold that’s his fault. He has been sent out to scare crows. In other places they have a doll to do it, made of sticks and old clothes. He has heard of it: English luxury. Here old clothes are not wasted.

…to first person in Ch. 3, with a periodic sentence that swirls the reader into Hunter’s own clinical fascination with his task:

I can tell you that there are no ghosts. If there were, they’d haunt Wullie, would they not?

And haunt me. But don’t think it. It’s a slab of butcher’s meat you have to haul, head waddling and hands flapping; the rigor’s passed by the time their keepers knock at the door, and they’ve once again a semblance of flexible life, yet they’re heavy, they don’t help you, you have to drag them, and their faces are fallen in, their noses are rims, sharp edges of falling flesh, and their lips are invisible already, shrunk back against the gum.

* There can be a particular magic to the forbidden, the strange, the weird – in a word, to the transgressive – and while you shouldn’t abuse that magic, you can and should trust it. I found this in fellow Southerners – Faulkner (As I Lay Dying, which I read for the first time at 15), Flannery O’Connor (ditto), and my former teacher Barry Hannah – and in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, from a book-review blurb in the old Seventeen magazine. I found it in Stephen King, my high-school addiction (I’d still put The Shining next to Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom, and Beloved as great works of American gothic.) And I found it in the rural Southern world around me, where accident and danger jostled with wonder and beauty. Mantel doesn’t shy away from violence or heartbreak . But she also reminds the reader: these are people, too. Here. the Giant travels through a starving Ireland toward London, offering a woman and her dying child the only thing he has to give:

The Giant and his train enjoyed nettle soup, and before the craving became acute Vance appeared with his flasks of the good stuff. Squatting in the cabin of the woman, the Giant told these stories: the earl of Desmond’s wedding night, and how St. Declan swallowed a pirate. All the town had come in, some bringing a light and others a turf for the fire, listening to the tales and praying in between them. When the death agony arrived, O’Brien took the child onto his knee, so that the rattle in his throat was interlaced and sometimes overlaid by his light, mellifluous tones, that tenor which surprised the hearers, coming as it did from a man so grossly huge. He tried to fit the cadence of his tale to the child’s suffering, but because he was a fallible person there were moments when it was necessary for him to pause for thought; at these times, the mud walls enclosed the horror of laboring silence, the scraping suspension of breath before the rasping cry which brought the babby back to life for another minute, and another. His body sleek with hair, his bones thick as wire, he looked like a mouse under O’Brien’s hand.

* Imagination keeps the “strange,” “supernatural,” and even “historical” from being just another path carved out for you in advance. As we read Nineteen Eighty-four, my first-year students and I are re-reminded by George Orwell to “choose – not simply accept” the language and thoughts with which we’re presented in composing our own. Monstrous Gothiness can (and often does) so easily become a cool dress-up disguise for our own predetermined opinions rather than a challenge to match their own wild strangeness on something like their own terms. (Kind of like conservative Mormonism delays the action and bloats the text of the Twilight series.) “I have endeavoured as nearly as possible to represent the characters as they probably were,” wrote Percy Shelley in his preface to his historical drama The Cenci (1820), “and have sought to avoid the error of making them actuated by my own conceptions of right and wrong, false or true; thus under a thin veil converting names and actions of the sixteenth century into cold impersonations of my own mind.” Mantel’s imaginative generosity and curiosity – what is it really like to be you? – lets her enter the wild sadness of the Giant’s final days, when he declares, “Everything fails, sir. Reason, and harvests, and the human heart.” But the Giant’s ultimate plea comes in a voice like Mantel’s own, utterly original and true to him as well as to herself:

Unless we plead on our knees with history, we are done for, we are lost. We must step sideways, into that country where space plaits and knots, where time folds and twists: where the years pass in a day.

In other words, the country of fiction to which Hilary Mantel welcomed me.