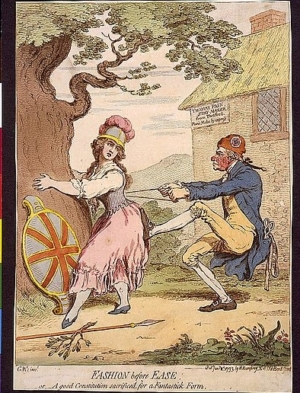

Left: The great writer. Right: Her tinfoil avatar.

“I was hoping for a great memorial to Mary Wollstonecraft…this isn’t it.” – Historian Simon Schama

I’m sure everyone involved meant well. I can’t wait to see how my next crop of “In Frankenstein’s Footsteps” study-abroad students will react to it [in a post-COVID J-term 2022 — from my lips to God’s ears!] But I’ve got to join the chorus declaring the new statue “for Mary Wollstonecraft” on Newington Green, near the site of her girls’ school, a missed opportunity. From its tinfoil finish to its protruding pudendum, it’s gratingly literal and jarringly bad. (“Like Metropolis meets the Birth of Venus!” someone tweeted, apparently intending this as a compliment. I think I’ll call it Tinfoil Mary.) But why? Can it be that, as people happy to call ourselves “feminists” without actually having read Wollstonecraft’s work, we’re more comfortable with Twitter-ready cliché than with the reality of messy, contradictory, refusing-to-suffer-fools lived experience that Wollstonecraft’s life exemplified? Can it be that we still equate nakedness, far too easily, with “female empowerment,” in a way Wollstonecraft herself never did? (See Rhiannon Lucy Coslett’s instructive comparison to Millicent Fawcett.) Can it be that we’d rather wave a presentist girl-power flag than consider a great thinker on her own terms and read her actual words and familiarize ourselves with her intellectual foremothers and have ideas about her and ourselves that develop over time? Why, I’m shocked. Shocked, to find that [simplistic thinking about public art and feminism] is going on in this establishment!

Ah, where to start. As someone who wrote a dissertation chapter on this – and is getting ready to tackle it again in my next book, fifteen years and a lot more experience [a very Wollstonecraftian word!] later – I’ll start where Wollstonecraft herself did: with what, exactly, we’re talking about when we talk about beauty, strength, and the female form. “Clothes define people and restrict people,” says Maggi Hambling, the sculptor of her silvery avatar, “they restrict people’s reaction. She’s naked and she’s every woman.” To be sure, on the face of it (ha!) there’s little to object to in that idea. Aren’t we supposed to be Proud of Our Bodies? Isn’t not hating your boobs and your tummy and all the rest of it generally acknowledged to be a Good Thing? Well, yeah. Wollstonecraft thought so too. But, as with so many things, her mindset about women’s bodies, including her own, is more complex and much more interesting than the social-media-ready form into which we boil it down. Our own often-tacit, seldom-unproblematic 21st-century assumption that nudity = power is simply not one Wollstonecraft shared. And we can get richly into it via what seems an antithetical object – the corset, or stays, as eighteenth-century women called them, the item of clothing Wollstonecraft laced around her ribs every day. Because clothes, like bodies, are complicated. And “restriction” – despite everything we might think we know about stays – is not the whole story.

Stays and Wollstonecraft seem an odd match – especially given how corsets (as we’d now call them) seem to promote the same simpering, wasp-waisted fashion-plate ideal Wollstonecraft overtly scorned. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), her general complaints about the “mischief of trimmings” adorning frivolous women include two possible references to corseting: a complaint about the “barbarous ligatures” which “deform” the body and her statement that “To preserve personal beauty, women’s glory! the limbs and faculties are cramped with worse than Chinese bands, and the sedentary life which they are condemned to live.” As governess and school-founder and mother, she’s vocal about women’s physical, intellectual, and moral education. “In the name of truth and common sense,” she writes irritably, “why should one woman not acknowledge that she can take more exercise than another?” A political radical and a Christian of a deeply Nonconformist stripe, she never wavered from her belief that men and women, as fellow creatures of God, are equally entitled to rights as creatures capable of moral virtue; mind has no gender and its capabilities no ceiling. Yet she’s also a realist: “I dread to unfold her mind,” she wrote gloomily of her first infant daughter, Fanny Imlay, “lest it render her unfit for the world she is to inhabit.” (Luckily, Wollstonecraft’s second daughter, Mary Shelley, was able to bend the world [of fiction, at least] around herself.) And despite presentist risk, everything in my research suggested to me that Wollstonecraft’s idealism and her realism meet in that ordinary object under her clothing: her stays, as much a part of her daily life as a bra is to a woman right now.

As a woman who wanted to be more comfortable in her body than she often was – and who had to go out and buy the groceries and meet her publisher and argue over dinner with the man who’d become her husband and do all the ordinary things any of us might do now without wobbling embarrassingly and uncomfortably all over the place — Wollstonecraft may have experienced her wearing of stays not only as an irritant but as a stabilizing, physically and socially supportive presence. At the time, stays were the closest thing to a bra women had: to get dressed, you’d put on your chemise (a nightgown-like undergarment), then fasten the stays over that, creating a kind of cradle and undergirding for your breasts through this combination of fabric and stays. If you didn’t have a maid to lace up your back, you could get stays that laced up the front. Therefore, stays helped tidy your body into a shape that was socially acceptable in prejudical ways, sure, but also in positive ones (how many of us would go braless to work, or out for a run?) Stays were also believed by some to help strengthen the muscles of the spine – helping a woman, literally, to stand upright. And the stays themselves were sturdy things, lasting for years. Heartbreakingly, when Wollstonecraft’s first daughter, Fanny Imlay, committed suicide in an inn in Wales, she was wearing Wollstonecraft’s own handed-down stays, still marked with the initials M W in thread.

Why do I think stays are an unexpected key to this woman who’s my own intellectual role model? Because images of strong bodies, and uprightness, and stays, and things that strengthen and stabilize women’s bodies (from outside and inside) and return them to women’s own control are all over Wollstonecraft’s work, particularly Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) and Vindication. To Wollstonecraft, the approval of men is a sort of sexual corset surrounding – and confining – a female body too weak to possess its own means of support and self-sustenance. “The woman who has only been taught to please,” Wollstonecraft writes, “will soon find that her charms are oblique sunbeams, and they cannot have much effect on her husband’s heart when they are seen every day, when the summer is passed and gone. Will she then have sufficient native energy to look into herself for comfort, and cultivate her dormant faculties? or, is it not more rational to expect that she will try to please other men [?]” As Jane Austen would write of Anne Elliot in Persuasion a generation later, sometimes a woman’s principles and her self-respect are all she has to sustain her in the world. Not coincidentally, these are the years when Wollstonecraft’s trying to establish herself as a professional and public intellectual in a world where asking for women’s rights was mocked as an endeavor as inherently ridiculous as asking for the rights of “brutes.” “In a comfortable situation,” Wollstonecraft writes, “a cultivated mind is necessary to render a woman contented; and in a miserable one, it is her only consolation. A sensible, delicate woman, who by some strange accident, or mistake, is joined to a fool or a brute, must be wretched beyond all names of wretchedness, if her views are confined to the present scene. Of what importance, then, is intellectual improvement, when our comfort here, and happiness hereafter, depends upon it.”

And this is where Wollstonecraft and girl-power cliche part ways, in a big way, in trying to think very hard about declaring human personhood in a world that limits personhood to your visible, sexual female body. Because getting naked might not be only declaring that you are Not Ashamed of Your Body. It might also be exposing yourself to the view of people (in Wollstonecraft’s world, men) who might flatter your body as “beautiful” and “sexy” and, by doing so, keep you in a neat closed box, firmly under themselves in multiple senses of that word, because sexy is all they think you can or should be. (A writer for the Gentleman’s Magazine of 1737 asserts: “Women are not form’d for great cares themselves, but to sooth and soften ours. They are confined within the narrow Limits of Domestick [sic] Offices, and when they stray beyond them, they move eccentrically, and consequently without Grace.” ) Being clothed might also be a means of power, a means of asserting mind as well as body, a means of asserting that the sexual identity with which female body is automatically identified in public is not a woman’s only identity, or even, in the circumstances, her primary identity. It might be a means of asserting that a woman’s body, in not being completely exposed to any controlling or exploiting gaze, is under her control, just like the words coming from her non-gendered brain. The pitfalls here are many, most involving the inherent hypocrisy of “modesty”-proscribing religious fundamentalism (Caesar’s wife — or “Mother” — must be above reproach, but Caesar himself will do as he damn well likes.) Wollstonecraft works through this conundrum over and over, again and again — what is the relationship between a woman’s mind, her body, and her soul? — and doesn’t really have a final answer, any more than we do. But, like us, she lives it.

Which brings me back to naked, six-packed Tinfoil Mary. In The Corset: A Cultural History, Valerie Steele theorizes that today, we’ve replaced the idea of the external corset with an internal one – the “muscular corset,” developed through yoga, Pilates, “core strength” building, and exercise to create a torso that looks trim and shapely all on its own. Like so many other women’s-bodies talk, this is positive and not. Sure, it’s an ideal of strength Wollstonecraft promoted in moral and physical terms – holding yourself upright, on your own, from inside, with no need for external help. And as bodies age and stasis and osteoporosis threaten, building strength is a good idea in all kinds of ways. Yet as disappointed commenters on Tinfoil Mary have pointed out, it also risks replacing one limiting standard of beauty with another. (Both are rebuked, to some degree, by Lizzo’s album cover.) This little nude figure does not work as a “metaphor for Wollstonecraft’s vision of personal authenticity” – which, again, should not be confused with our own too-frequent confusion of nudity with “authenticity.” Neither her work nor her biography support such a claim.

In my research, I found myself thinking a lot of the old phrase “stay against confusion,” a double meaning Wollstonecraft would certainly also have known. “To have in this uncertain world some stay, which cannot be undermined,” Wollstonecraft writes in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, “is of the utmost consequence; and this stay it is, which gives that dignity to the manners, which shews that a person does not depend on mere human applause for comfort and satisfaction.” Stay against confusion: a model of integrity. What do you rely on to keep yourself upright in the world, to reorient yourself and bring yourself back to what you know to be good and right and true and keep on working and writing for good? Is this the external support of customs, habits, friends, social networks, or the inward support of your own values, or both? And what does it look like to move strongly, actively, maturely, and compassionately through the world? We’re not lacking models of grown-woman-hood who can occupy multiple identities at once (like their suits) in the present – or in the past – if we only know how to read them with the care they deserve. Thinking about Mary Wollstonecraft as an eager young intellectual in the city – lacing herself into her stays, brushing her hair, gathering her papers, and setting out down the bustling morning street – knits me into a continuum of working, striving women eager to be considered for their brains, not (only) their visible bodies. And isn’t that where we all live, in one way or another?

And I’m left thinking, now, of lost opportunities. A statue that invites us to consider a generic, weirdly proportioned naked body rather than Wollstonecraft’s actual eager, searching face? Or to consider the words from her last, unfinished novel, Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman: “Gain experience – ah! gain it – while experience is worth having, and acquire sufficient fortitude to pursue your own happiness; it includes your utility, by a direct path.” Or to reflect on the heart-stopping musing from Letters from Norway (1796): “It appears to me impossible that I shall cease to exist, or that this active, restless spirit, equally alive to joy and sorrow, should only be organized dust…. Surely something resides in this heart that is not perishable – and life is more than a dream.” A lost opportunity, indeed. Luckily, we don’t need a lump of metal to remember Mary Wollstonecraft. We have her words, coming to new life with every beat of our own hearts. And we always will.