Lately I’ve been feeling challenged to keep mindful about spending. Three things have helped:

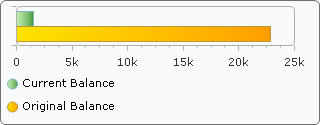

One, I consulted my credit-counseling service’s client website, where my progress chart looks like this:

What a great feeling. That’s just a little more than $1,500 on one card to go, compared to what was $22,000 on seven cards four years ago. Best of all will be when the green bar disappears.

Two, I attended the Nobel Peace Prize Forum this weekend, surrounded by colleagues, students, and friends – seeing so many students there and hearing their thoughtful, impassioned voices was a great delight. Vivid in my memory is Shirin Ebadi on stage in front of a huge, rapt crowd, no-nonsense in a simple gray pantsuit, her feet in their black lace-up shoes just brushing the floor (she is a small lady with a large presence, and even larger moral authority). Her face is warm and flashes with humor, candor, and passion. “The victory of women,” she declared through her translator, hands jabbing the air for emphasis, “will be the victory of democracy. Because women’s rights are the forerunner of democracy, everywhere.” Only when asked did she describe her incarceration by the Iranian government for her legal work on behalf of women and children. “A little cell,” she said, pausing for the translator to render her words. “If I had been a little taller – and you can see, I am not tall – I would not have been able to stretch out in it to sleep. Dirty carpet in the floor. A light that was always on. But I was only there for twenty-five days. I have had clients who have lived under these conditions for over a year.” She scooted forward in her chair, hands outflung, sweeping the whole audience with her gaze. “You have to fight to defend the freedoms you have gained,” she said. “Democracy is like a flower, in a pot in your house. You have to water it, care for it. You cannot water the flower with a big bucket once, and then forget about it for a month.”

Yep, it was inspiring, all right. And full of little moments of self-examination. Had I known I would be photographed with Dr. Geir Lundestad, eminent historian and director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute – a reporter from the local paper snapped a picture as I stood talking with him after his lecture – I might have taken a bit more trouble with my hair and clothes. I might not have ridden my bike, which can be a bit tough (especially in winter) on snazzy arrangements of hair and clothes. But didn’t I walk to and from school yesterday, and ride my bike today, because I believe in what the Peace Prize Forum teaches so powerfully – that in Gandhi’s words, I have to be the change I wish to see in the world, and that change begins with small actions, every day? Wasn’t I so absorbed in conversation with the man who picks the prizewinners – and who had just described, from the stage, friction with the Chinese Vice Foreign Minister over Liu Xiaobo – that my hair was not the most important thing on my mind? Hadn’t I just come from Alisa Gravitz’s great talk on “Daily Actions for Building a Green Economy?”

And hasn’t “my appearance” too often been just an excuse for firing up a ton of metal and glass and rubber and lighting some dinosaur bones on fire to drive a mile and a half to work, even as I bemoan winter weight gain, lack of time to exercise, et cetera? To wear non-walking shoes, preserve the hair I too-often artificially smooth (I’ll have to save the full curly-hair angst meditation for another time), paper over the fact that I am not managing my time well enough to get up early enough to pack an extra pair of shoes and equip myself to walk? I can still look good if I think ahead and take the time. Aren’t I just seizing on what Pema Chodron would call the habit of scratching the itch of non-mindfulness, the habit of habit itself, leaping into what Tobias Wolff has called “the sweetness of that voice in each of us that sings the delight of not being responsible, of refusing the labor of choice by which we create ourselves?” And isn’t that, like, wrong?

Come on, I tell myself, as gently as I can. I think it’s time for you to get real. This bit of carelessness with money, these little re-eruptions of some bad habits, the midweek binge on jellybeans, are signs that non-mindfulness is creeping in. It’s time to put some ground back under your feet, to feel some actual wind – and even, this morning, a little flicker of snow – on your face, to sense the joyful squish of the wakening thawing ground under your boot-soles. It’s time to do what it takes to bring the world back to life in your mind. As Hannah Arendt would say, it’s time to give physical reality and the consequences of your being in it “a claim on [your] thinking attention.”

So I went back to a favorite technique connected to the third thing that has been helping me lately: reading Your Money Or Your Life by Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez. (Yeah, I know – I can’t believe it’s taken me so long, either. This book is great.) They urge you – gently but firmly – to calculate your real salary and the real cost of what you buy in “life-units” – all the time you actually spend at, and getting ready for, and decompressing from, your job divided by the money you actually make from it, or your “real hourly wage.” The amount of hours you may reasonably be expected to live goes into the equation too. Dollars spent on something divided by your “real hourly wage” = hours of life energy. What you end up with is a sobering but transformative tool for evaluating how you are really spending – in every way – what Mary Oliver calls “your one wild and precious life.” Then you have the best possible tool to examine impulse purchases, or even those you argue with yourself aren’t really “impulse purchases” but “needs” – is this worth spending one hour, two hours, three hours of your precious life energy for? Do you really get that value back? Because you’ll never get that life energy back. It’s gone. And knowing that its dignity and endless possibility have been squandered on what Robin and Dominguez call “gazingus pins” gives you a sick little twist in the gut that just might help you make the change, because it makes the consequences of your actions real. “The key,” they write, “is remembering that anything you buy and don’t use, anything you throw away, anything you consume and don’t enjoy is money down the drain, wasting your life energy and wasting the finite resources of the planet.”

So as I am trying to wean myself back into walking or biking rather than driving, I have developed a new tool to keep it real: dinosaur bones. Think about it. Fossil fuel = dinosaur bones. And this is where I get to do a writing exercise in my head: how specific can I be about the bones? How can I imagine their original owners, what brought them to the spot where they died and were pressed into the ground and became, slowly, slowly, petroleum? When I slam out of the house, running late, and fire up the car, who’s paying for it – a juvenile Stegosaurus, hooting in distress as he sinks into the tar pit? A ridgy-backed Iguanadon, the so-called dinosaur of “questionable class?” (I think I’ve dated a couple of those. Or maybe that would be the current leadership of Iran….) A little light-footed Compsognathus, Edmontosaurus with his droopy Churchill jowls? (Wouldn’t an elderly English statesman be named Edmontosaurus, if he were a dinosaur?) What irreplaceable chunk of vertebrae, what liquefied lumbering animal selves so irretrievably lost, are disappearing into my tank, forever, burned away as if they’d never been, because I hit the snooze button one too many times?

The eastern cougar went extinct this week. The radio news reached me on the morning of March 3, between the hiss of my hot shower and my hairdryer’s buzz.

Oh, how many creatures die because of what we humans think we “need.”

I carried my (reusable) bag of groceries into the house and unpacked them tonight. Ah, luscious Greek yogurt. Mozzarella cheese made by Beth, right in our co-op. And a bag of oranges. Shaking them out into the bowl on my dining room table – so bright, so beautiful and sweet — I realized what I still held in my hand: a red plastic net. The vision paralyzed me: this net floating in the ocean on its long path from the house in which I Throw It Away, drifting — perhaps on the surface, perhaps lower – browsed by a curious creature I could only hope would be small enough not to get caught. I balled the net up and put it in my Useful Containers for Something bag. You can hang a ball of garden twine from this net in your garage. Poke the free end through the mesh and unspool at will.

And you can buy things next time that don’t come in nets. Six-pack rings: everyone knows they choke turtles. But who thinks about the nets? I guess I do, now. It’s all connected. So are we.

So I try to make it real. Pedaling home tonight, I savored the light and unmistakable tang of spring, of melting snow and evening sun. And I imagined I held in my right hand a chunk of bone – a million-year-old vertebrae or a crumb of jaw, maybe, with just one tooth still attached. In my mind’s eye, I held it, I looked at it. And then I put it back into the ground.