Every year, fresh from days away at my family home where there are friendly differences about — shall we say — organizing styles, I return to my own little house and see the place with fresh eyes. Somehow, as good as I usually am about filing and purging, the place just looks full. The line of various cooking-and-gardening-how-to books on the counter is longer than ever (with some stacked on top), the coffee-table stacks of books are deep, the drying peppers still hanging from their nail in the kitchen need to be put away, the refrigerator is now completely covered with photos and with drawings by my niece and nephew and other special children friends. The urge to clean and purge seizes me again, and I remember some organizing guru’s words that if you fill your house with stuff – no matter how beautifully organized it is – there is no room for more stuff to enter in. You are blocking the flow.

There’s some truth to that. You can stave off, at least for a little while, feelings of emptiness, loneliness, inadequacy, or scarcity by stockpiling whatever it is you fear being without, but those feelings always come back – they come from a place deeper than your checkbook can really touch. And keeping yourself open to the new — remaining expectant, waiting for whatever might come into empty spaces in your life, literal or figurative — is hard. It can feel an awful lot like just plain lacking, like whatever state of “being without” triggers your worst feelings or fears. So keeping yourself busy building up the illusion of plenty, surrounding yourself with stuff, can be not only about keeping those fears away but asserting your identity: I am this because I have this or do this. I am not that, not anymore.

Buddhists, of course, would call this attachment: the error of relying on the temporary things of this world to give an illusory definition to the immortal and containerless self. (Plato, as in “The Allegory of the Cave,” would say something similar.) Christians, as I was reminded during a visit to my hometown church this holiday, might also call this the Mary-and-Martha syndrome: in the gospel of Luke, Jesus visits two sisters, Mary and Martha. Mary stops work to sit at his feet. Martha keeps bustling around, staying busy (“cumbered about much serving,” in the King James Version, and isn’t that just how it feels?), and then she complains to him, “Lord, dost thou not care that my sister hath left me to serve alone? Bid her therefore that she help me.” Jesus replies, “Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things, but one thing is needful, and Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her.”

Thinking about this, I thought: maybe this is the sorting device I need to help purge, again. What is going to help me get closer to what is real and enduring, and what am I clinging to not only because it may be superficially useful but because it shores up an illusory “identity” I only think I want to have? (I have let subscriptions to, say, decorating magazines lapse over the years for this reason; $500 for a sofa pillow will never be reasonable, in my world.) Why not let go of things or processes that make me feel like Martha at her worst: clinging to an ultimately self-aggrandizing illusion of “busyness” that isn’t really going to matter in a year, and just makes me tired and whiny now? (The Mary and Martha story has more applications to college-professor life than any of us want to admit.) But then I found myself back at my familiar place of riddling discernment when it comes to all this: books, and things that I think will help me write them.

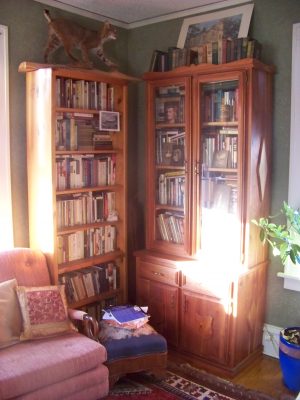

Let this corner of the Cheapskate Intellectual abode stand for the rest of it – and for its organizing challenges. Yes, there are a lot of books. And there are objects each with a story: the cedar-wood glass-fronted case, made by a patient of my father’s, used to be a gun cabinet (you can still see the gun-barrel rests behind the fitted-in shelves), the Oriental rug came out of my parents’ house in a situation that still causes us a certain rueful hilarity, the little footstool with books upended on it was embroidered by a great-aunt, the pillow on the chair (recovered from my late grandmother’s house) is made from a genuine Indian sari and came from my globetrotting friend Kim, and the lemon tree, which just produced its first crop of lemons, was waiting for me with fresh blooms when I got home. The photograph on top of the cabinet was taken and hand-tinted by a friend of an old Victorian house in my near-hometown that’s gone. The stuffed bobcat is real. She has a story too.

Let this corner of the Cheapskate Intellectual abode stand for the rest of it – and for its organizing challenges. Yes, there are a lot of books. And there are objects each with a story: the cedar-wood glass-fronted case, made by a patient of my father’s, used to be a gun cabinet (you can still see the gun-barrel rests behind the fitted-in shelves), the Oriental rug came out of my parents’ house in a situation that still causes us a certain rueful hilarity, the little footstool with books upended on it was embroidered by a great-aunt, the pillow on the chair (recovered from my late grandmother’s house) is made from a genuine Indian sari and came from my globetrotting friend Kim, and the lemon tree, which just produced its first crop of lemons, was waiting for me with fresh blooms when I got home. The photograph on top of the cabinet was taken and hand-tinted by a friend of an old Victorian house in my near-hometown that’s gone. The stuffed bobcat is real. She has a story too.

This is essentially the aesthetic with which I grew up, and which will always be my favored one: layered, historical, Southern-rural, favoring the hand-me-down and storied and repurposed over the bought. But I have one big challenge here: books. As any working writer or intellectual (cheapskate or otherwise) knows, books are truly a unique organizing challenge because of their relationship to ideas and to the moving, shifting, organic life of thought itself, which gets prompted and spurred by random sights, juxtapositions, objects, reminders. These moments come not just from physical objects (like my antique cardboard Thomas Edison phonograph-cylinder container, or hundred-year-old photographs of Norwegian immigrant couples on their wedding day, scavenged for a dollar apiece from local antique shops, or my great-aunt‘s college diploma with her ex-husband’s last name razored out), but from the books themselves. To get ideas for courses, I scan my own shelves. To keep a project “alive” in my mind, I keep some books related to it on my desk, even if I am not working on it at that time. Over and over, I’ll be writing something and remember not just a line or passage but a visual flash of the note I wrote in my own copy of that book, next to that passage, and then when I go get it, the whole structure of the original thought will be there, dangling like one of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s straw mobiles in my mind, swaying gently back and forth and reflecting the light. I rip out and file magazine articles, too, for this reason. In fact, while I was writing this, I remembered James Wood’s great essay on his father-in-law’s library a few New Yorkers back, with one of the best explanations ever of why we collect more books than we can read: “The acquisition of a book signalled not just the potential acquisition of knowledge but also something like the property rights to a piece of ground: the knowledge became a visitable place.” Yet Wood also describes, as he helps his grieving wife sort that library, “how … I began to resent his avariciousness, which resembled, in death, any other kind of avariciousness for objects.” And that’s a perhaps-troubling contradiction at the heart of book-stockpiling, of which I’ve always been guilty, signaled by the perpetual question any book-hoarder gets (“Don’t they have libraries for that?”) or by Wood’s own question: “Isn’t a private library simply a universal legacy pretending to be an individual one?”

True enough. Yet as I look around at my own busy and happy little house with all its stuff, I remember (from my own copy, of course) what Shannon Hayes says in Radical Homemakers about how a home where people are living and doing and making things is going to be a natural ecosystem, with its own type of “happy entropy:” bread dough rising on the counter, piles of books to read, “chicken poop on the porch furniture.” Demolishing the myth of perfection, Hayes quotes Emerson: “a house kept to the end of display is impossible to all but a few women [“and men!” Hayes adds] and their success is dearly bought.” The books are signs of projects in progress, new frontiers into which to expand and grow, tangible signs of mental life. And I guess this is the key to maintaining peace with the objects in our own home ecosystems: toss what gets in the way of that real, true life or is only a clinging to an old, false habit or self-image, but be aware that ultimately, your home has to please, primarily, you.

Can so relate to this – the beloved layering of a life, as well as the zeal of the purge. As long as both of them are in harmony, a “full” house does help you feel full in your life. And one thought, I love using paperbackswap.com for those books I enjoyed but don’t need to keep–and then I get to get new ones in their place :). Love, A

Thanks so much! “The beloved layering of life.” That is awesome – typically! 🙂 xxoooo A

🙂 – and I love your reference to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s straw mobiles, love that passage from her book about the airy golden structures . . .

Thanks! I used to always wonder what those looked like… I developed a picture in my head that might or might not have looked like the real thing, but that made me happy anyway.

I felt so at home reading this! Cozy, yet challenged. Like a book laying beside, say…a Kindle. Thank you, Amy, yet again–you capture moments with keen reflections that illumine gently, with faithfully observed shadowing-giving dimension, gifting recognition, gleaning wisdom.

Thanks, Mike, for reading, as always!

Your piece reminded me of the days when I go searching for a book or a passage somewhere, and I get sidetracked…….off to another book or paper I’ve saved somewhere. Sometime it goes on and the things I had on my to-do list are left undone…….but what a wonderful trip along the way…….getting a bit lost if often the best adventure!

Thanks, Sue! (This happens to me a lot as well. 🙂

Every few months, Eric and I attempt to purge our bookshelf…we live in a tiny apartment, and our bookshelf is at capacity and then some, not to mention the giant stack (no exaggeration, I promise) next to my nightstand, and the ever-present–and enormous–pile of library books on our “entryway table.” …in quotes because it’s pretty much just another ikea-like bookshelf upon which we happen to stash our keys and bags. I really do feel comforted by the close proximity of the books I’ve read, and those I mean to read. I am often reminded by my husband that the library will be around for awhile, and that I absolutely do not have to check out every single book I might want to read RIGHT NOW. 🙂

beautiful post, as always – much love, and Happy New Year!

kh

ah, yes, i see your english-major career trained you well…. 🙂 welcome to the club! hugs, a

I see myself in your words about books, history and layering. It does seem that the physical often holds or triggers the memory of our histories. Beautifully written, heartfelt and true. Thanks for your kitchen table wisdom. kas

Thank you so much!!! Hope y’all are well and enjoying the winter! I have really been enjoying your blog too.