Longtime Cheapskate readers, brace yourselves (or y’all’s selves) and check the temperature in hell: I’ve got a smartphone. An IPhone 7, safely encased in a red LifeProof jacket with a dorsal stripe of turquoise (exactly like my front door; the flash of haint blue, I hope, similarly protecting my goings out and comings in.) I’ve owned it now for a month and a half. And while my beliefs about smartphones are fundamentally unchanged — they’re fiendishly insidious, and will bend your awareness around themselves until they have altered the temperature inside your brain, and talking on the thing means braving that icky, sticky screen-to-cheek contact — I can’t deny it’s eased my life more than a bit. While I’ve not become a creature of the phone as much as I feared (and don’t see Twitter or Instagram in my future), I can detect distinctly pre- and post-iPhone varieties of consciousness. And that feels significant.

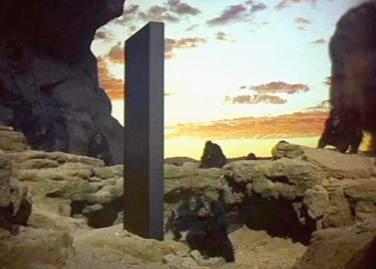

The spark? Two big study-abroad teaching assignments coming up in the next couple years and the shorter trip last month to prepare for them. I stalled and stalled and kept relying on my trusty old pay-as-you-go flipphone and finally made the decision late this April. In three days, I had my new phone in my hand, sleek and black and mysterious as the monolith in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” with me as the curious beast poking at it and hurling legbones in the air.

At one level, I’m very much safer, able to get maps and have a disembodied voice read directions to me on the admittedly rare occasions I drive somewhere I don’t already know. (And of course students overseas will be able to contact me more easily.) But much of that safety is really the great Let Me Float on My Assumptions button we are always hoping the world will hit, a portal to a kind of Huxleyan corporate/intellectual soma. Everything about its design is designed to slide us thoughtlessly into its mental and commercial world. A brand-new iPhone comes with no instruction manual. Turn it on and it sets itself up. Google setup and it takes you right to Apple’s own site, where you still can’t find exactly what you need. But that doesn’t matter. You are in the grip of that faintly dry-mouthed, itchy-palmed consumer excitement that switches off any common-sense tech-skepticism you might ever have possessed or (ahem) written about in your (ahem) forthcoming book. “Recognize my location/upload to the cloud?” Sure! Buy a new waterproof case? Absolutely! (How like a small fragile animal this thing is, how slippery, how costly if I drop it.)

And, just in that one flash, and thankfully only for that instant, how weird — even to me, who wrote about them and lived within them until a month and a half ago — the anti-smartphone, data-wary viewpoints of tech-skeptics seem. Now I understand as never before what my students, digital natives (just less than) half my age, are up against. In their lives as reasonably aware persons, and now as young adults, they have never been without this constant, vaguely self-monitoring presence, like a parent, like a personal shopper, like a security camera you could train on others or that could be trained on you, usually both. Immediately I noticed my eyes were having trouble adjusting to my new toy, as they never had to, say, a new laptop, although they’ve added this new lens calibration to their repertoire now. When you look up from the screen, something has changed. A level of freshness and immediacy is gone. (Where is it fled, the glory and the dream?). The thing that chases it away follows you, lives in your pocket or bag, nestles smugly, and snugly, against the surface of your attention. You have it. It has you.

It is good for a few big things. Photos, videos, the text systems by which you can share those photos instantly with someone you wish was with you. Capturing 30 seconds in the woods around my favorite writers conference. (Alongside the words in my notebook, those images and sounds will always take me there.) Dialing up music while unpacking in a hotel (I still hate television, especially in hotels). London Review of Books podcasts. The pedometer, which has tilted me down a dismal slide toward the purchase of one of those watches that tracks and barks commands at you like the wiry woman on Winston Smith’s telescreen in Nineteen Eighty-four. But I am walking more since I’ve had this thing, even bought one of those armholders like a blood-pressure cuff. The screen showers green confetti when you surpass 10,000 steps! How small our rewards with which we are content. How weirdly accountable to a machine. And yet. I’ll still strive to keep myself in control of this experiment, swimming warily in this estuarial zone of consciousness and technology, listening through skin and brain for the undertow.

…and it adjusts my hearing aids 🙂