At first they look like sites of human sacrifice, some kind of Victorian Thunderdome-meets-Coliseum on the banks of the sweet Regents Canal with its houseboats and its ducks – round rings of iron columns, enclosing a space somehow charged, vaguely menacing. Step inside the circle and do battle! But they’re actually called gas holders, or gasometers. They work kind of like a coffee press, with a central cylinder that can move up and down to push fuel through the city’s pipes, lighting streetlamps in Sherlock-Holmes-ian fog and houselights of the sort Charles Boyer used to herd Ingrid Bergman into a little corner of domestic hell and brightening rooms for artists and clerks and ordinary folks. You can see them on the Thames river shuttle from Greenwich back through Docklands into the city, too. This cluster’s now clad in gleaming ironwork, striking and modern yet also still themselves. And now they’ve been given new life.

On the glass windows of each new tower’s ground floor is a sleek decal: N1C MARKETING SUITE. Apartments ready to move in today, from *£825,000. *Prices correct at time of printing. Beyond the glass, the walls and floors are bare, the ductwork is exposed, and the sunlight slants unbroken through space. Primed by walks through this palimpsest city, Brexit economics, and Anna Minton’s Big Capital, students and I crane our necks toward the apartment windows but can’t tell whether anybody’s living here. Are those a real person’s books and photos on a shelf or a model-apartment staging? Students observe astutely that “flat” sounds British and rental-ish, but “apartment” sounds international and owner-based, reflecting the reality (reported by Minton and the international press) that many expensive properties like this are bought by foreign investors, not Londoners, and often stand empty. Ben Judah’s This is London has a chapter on the Filipina maids who cycle through hollow mansions in Mayfair, cleaning already-spotless floors, changing un-slept-in sheets, and leaving again, obeying the directives of invisible voices on the phone. Rough-sleeping in the city is epidemic. New ads for the Metropolitan Police have appeared on the Tube, inviting prospective applicants to make a difference (and these officers do make a bigger and better difference, more often, than anybody knows). Starting salary, as listed in the ads: £30,000 a year. A television ad for The Economist shows an inquisitive young woman growing into a teacher, a profession regarding which I feel the same sense of downright holy mission and responsibility as my late father, a surgeon, felt about medicine. Starting salary – well, we all know what teachers make.

This city I love is one of so many places where realities are striving for balance, all over the world. Nice things cost money. Saving worthy historical structures doesn’t come cheap. Entrepreneurs need the freedom to build on good ideas and the responsibility to do so wisely in a world where “indefinite, unlimited growth” is being exposed as the myth it always was. Schools need teachers with good training and support, updated and plentiful books and equipment (books still accomplish more for students’ long-term development than computers ever can), and physical safety, given how fear can cripple curiosity, investigation, and ingenuity. This is true in life beyond school, too. No one should have to fear the financial ruin of a health crisis or old age (which comes for all of us, eventually.) Homelessness is higher than I’ve ever seen it, and this is my eighth visit in the last twenty years. Fossil fuels, once apparently so limitless, are dwindling in supply but swelling in catastrophic effect (George Orwell grasped the tail of this truth, just slithering into view, in 1936.) All these things are true.

As ever, the question is: how to power a good society, with energy and money, so it’s available for us and those alive when we are gone. Because energy and money in the right places can do real good. I’m not a fan of 825,000-pound flats in an era of housing crises and rough sleepers. I am a fan of repurposing and saving buildings into public spaces that, on this warm late-February day, are drawing people into the sun to lounge and walk and be together. Here at Kings Cross, a complex of Victorian brick coal warehouses, renovated and repurposed as The Coal Drops, are busy, happy, alive. Food trucks stand in inviting lines and art students cluster and smoke and three lithe acrobats in bowler hats and bowties, with prosthetic blades attached like stilts to their feet, flip and leap to the screeching delight of children, without cushions or a net.

Power. Sustainability. What are sources of power available to us, within us, that actually sustain? That build our capacities to live as better people in a better world?

*

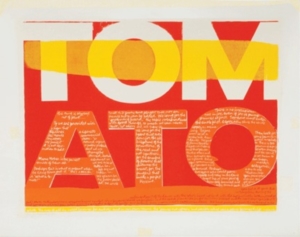

Corita Kent (1918-1986) was a nun who loved Pop Art and advertising. She did prints and silkscreens in Day-Glo colors with words rippled or blown up or distorted: COME ALIVE. SEE THE MAN WHO SAVES. WONDER BREAD. Sister Corita’s work helps you see even our ordinary commercial landscapes as she saw them: the word as the Word, the divine immanent in the ordinary. Which is after all the nature of the entire faith. Bread, wine. The Word became flesh and dwelt among us. Meaning and mystery are always already here, between birth and death, in this place. And so is joy.

Corita Kent followed Virginia Woolf’s advice to aspiring novelist “Mary Carmichael” in A Room of One’s Own: look into the shop and write about what you find there, without dismissing it as unworthy of concern. She was genuinely puzzled by people (like me) who’d campaign against billboards. “I hate to judge people,” she said, “but I think [the people who want signs removed from countryside] might not enjoy those trees and hills as much as those who can delight in both.” She called her art “illuminations,” as in the illuminated capitals in a medieval copy of the Gospel: “taking a word and joining it with something that is visually exciting,” she said, “shows a kind of reverence for what the world says, a kind of excitement about it.”

In the London Review of Books, James Meek (describing the TV show “Mad Men”) writes, pointedly, “If you don’t have a product, what do you have? Nameless things, unlabelled things, things without brands and logos, generic things, free things, things without margin: love, death, loss, disappointment, unpossessed beauty.” This is my own view of what commercialism [I once worked in advertising, to be fair] and social media do to the soul. Yet Sister Corita is turning me around, educating me in the Socratic sense (“for education is not the facility of putting sight into blind eyes,” his student Plato records him saying in The Allegory of the Cave, “but the turning of the soul to recognize the good.”) As a man is, wrote William Blake, so he sees. Therefore, in order to see different, you might have to be different. Keep your eye on the shifting dot on the map where these two vectors meet – especially as you travel – and you may yet figure out something of how to live.

Corita Kent’s work is on view now at the House of Illustration in a repurposed Coal Drops building, and it’s a marvel: a wash of color and spirit and grace and light that makes me feel irradiated, rinsed, brightened and cleansed inside and out. In two great towers in the gallery are broadsides of Corita Kent’s studio rules, free for anyone to take:

RULE ONE: Find a place you trust, and then try trusting it for a while.

RULE TWO: General duties of a student: Pull everything out of your teacher; pull everything out of your fellow students.

RULE THREE: General duties of a teacher: Pull everything out of your students.

RULE FOUR: Consider everything an experiment.

RULE FIVE: Be self-disciplined: this means finding someone wise or smart and choosing to follow them. To be disciplined is to follow in a good way. To be self-disciplined is to follow in a better way.

RULE SIX: Nothing is a mistake. There’s no win and no fail, there’s only make.

RULE SEVEN: The only rule is work. If you work it will lead to something. It’s the people who do all of the work all of the time who eventually catch on to things.

RULE EIGHT: Don’t try to create and analyze at the same time. They’re different processes.

RULE NINE: Be happy whenever you can manage it. Enjoy yourself. It’s lighter than you think.

RULE TEN: We’re breaking all the rules. Even our own rules. And how do we do that? By leaving plenty of room for X quantities.

HINTS: Always be around. Come or go to everything. Always go to classes. Read anything you can get your hands on. Look at movies carefully, often. Save everything. It might come in handy later.

There will be new rules next week.

Be here, be around, show up for things – that helps you do the work and the work is what moves you forward. Work is discipline but discipline is also – that vital, Virginia-Woolf-ian word – liberty, and it enables liberty. The liberty of artists doing their thing opens that space of liberty all around them, into the unspecified future where we stand and touch hands with him, and where we, too, are free – only ourselves, only creatures moved by sensations and by words and by that within ourselves which must be spirit, that which cannot be sold or commodified and often cannot even be named and is all the more valuable for that.

Corita Kent plugged the spiritual into the political and electrified both. The exhibition includes a screenprinted image of her friends, the priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan, burning draft cards with homemade napalm to dramatize what they saw as the death-dealing nature of war. “I am in Vietnam,” cries a print of a poem by her friend Gerald Huckaby, “who will console me?” Multiple prints invoke the words of Martin Luther King and invite viewers to “give a damn about your fellow man.” Another print juxtaposes the cover of LIFE magazine on “the Negro problem” with an historic English engraving of bodies in a slave ship and Walt Whitman’s “I am the hunted slave” lines from Song of Myself. She is proudly, profoundly Catholic and American and intent on shining the light of spirit on both to hold them to account. Her poster for George McGovern’s 1972 campaign (two years before my own birth) invites, “Come home, America.” A captivating “circus alphabet” celebrates spirit of love and play, with words Kent found meaningful juxtaposed with vintage images: “…damn everything that is grim, dull, motionless, unrisking, inward turning, damn everything that won’t get in the circle, that won’t enjoy, that won’t throw its heart into the tension, surprise, fear, and delight of the circus, the round world, the full existence.” These words come from Sister Helen Kelley, president of Immaculate Heart College (Corita Kent’s home institution), who defended Sister Corita’s work against doubtful Monsignors and other church fathers. Now they ride along in my notebook every day.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a four-part banner reading POWER UP in giant multicolored letters, with Daniel Berrigan’s words underneath. “Christ is merciless about the poor,” it reads in part. “He wants them around – always and everywhere. He’s condemned them to live with us. It’s terrifying. I mean for us too. It’s not only that we are ordered, rigorously ordered, to serve the poor. That’s hard enough; Christ gives so few orders in all the gospel. But the point is, what the poor see in us – and don’t see, too. We stand there, American, white, Catholic with the keys of the kingdom and the keys of the world in our pocket. Everything about us says, Be like me! I’ve got it made. But the poor man sees the emperor – naked. Like the look of Christ, the poor man strips us down to the bone. And then if we’re lucky something dawns – even on us.”

Stripped down to the bone by the gaze of the poor: that’s not an abstraction for me in this city now. On the street a woman – wild-haired, weathered, tooth-snagged – grinned sarcastically into my hastily-averted face. “So, is that your Bentley on the corner, then?” she asked. (There actually was a Bentley there, three steps away.) Three people huddled on my building’s front stoop, mumbling apologies: “Sorry, love, it’s just so cold.” I brought them apples and granola bars in a plastic bag, a virtuously brandished widow’s mite. And a mite is what it is. That flush of shame is what I deserve. On Euston Road a man hunkers against a wall, eyes squeezed shut, face wet with tears, mouth open in a soundless howl. Dives, the poor man, is always with us, always asking what we are, and why. Daniel Berrigan is right about that.

*

Look down from the House of Illustration into the Regents Canal: a ribbon of time, threading through the fever of the commercial now. Houseboats still travel between its concrete banks; set out on this path and you could walk all the way to Maida Vale in the west and Limehouse Basin in the east. One boat houses a barbershop, with garlands of greenery around the door and some Sinatraesque crooner blaring from a radio. Bags of fuel for heaters and potting soil for containers are stacked on roofs. There are curtains drawn over windows, windchimes, a little iron statue of a Yorkshire terrier.

This is also where you find a boat full of books: Word on the Water, a houseboat fitted out with shelves and vases of flowers and boxes of records for sale, a sign reading BOOKSHOP on the roof. Nobody taller than five-eight or so can stand upright unless they’re right underneath the skylight, but once in the boat, you don’t mind. It’s cozy in there, smelling pleasantly of cloves, old paper and wood, with a selection both used and new leaning toward classics and sustainability: the new hardback of Orwell’s selected writings, Angela Carter (the creator of Sophie Fevvers would have loved this boat), a capacious set of Penguin Great Ideas. I hang out for a little while with one of its owners, Jon, and his brown-and-white dog Star, aged fifteen; she came from a rescue shelter in Ireland. “Never spent a day locked up inside, other than that,” Jon says. “She just likes to be out. To have something to do.” He throws her tennis ball and she leaps after it. A cyclist goes tearing past. “She only chases them,” Jon says, “when they’re going too fast!”

Jon tells me a little about the clash between his small floating bookshop and the commercial boom. “We’re off message, you see,” he says wryly, gesturing at the new construction above and behind. “All this is new in the last three years.” Millions of pounds have been spent to retrofit what were once derelict buildings. Kings Cross was indeed a rough-trade zone then, but it’s hard not to feel that something has in turn been lost, especially as shelter in the city is hard to come by for so many. This little boat survives, and fills a need. I’ve been back to Word on the Water with friends and with students, and each time it’s the same: a huge variety of people (and lots of children) magnetized by the boat and its music and its temptingly arrayed rows of books, their faces opening unguarded in the instant they spot it. They go inside, they sit and hunker and browse and peruse. Words are still a source of value and illumination, of textures of experience beyond the commercial ones. Books are still a private space, a space for communion of private selves with the world.

Art and need and poverty and human yearning: what to do about it all? The time is out of joint, Hamlet says. The time is always out of joint, a Corita Kent print responds. My favorite of her works, it’s titled “The Juiciest Tomato of All.” We yearn for the fully packed, the circle that is so juicy and perfect that not an ounce more can be added, reads the text. We long for the “groaning board,” the table overburdened with good things, so much we can never taste, let alone eat, all there is. We long for the heart that overflows, for the all-accepting of the bounteous, of the real and not synthetic, for the armful of flowers that contines the breast, for the fingers that make a perfect blessing.

We long for sources of power that activate not our wallets but our souls.

*

Across the canal from the gasometer-flats is the lock-keeper’s cottage with a little garden strung with fairy lights and benches. It looks a little like Mr Wemmick’s domestic paradise in Great Expectations, with the little moat he retreats behind to shut out the world. Students and I hang over the bridge railing and watch as a houseboat is lowered and released – a homely and matter-of-fact piece of the past, obedience to the laws of water and gravity and motion that haven’t changed from Anglo-Saxon times to this. And all around us is the Borough of Camden. In the mad, brilliant cult film “Withnail and I” (1987), Richard E. Grant and Paul McGann are art-school slummers here, careening through the streets in their decaying Jaguar MK2 as wrecking balls slammed into Victorian walls and Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower” blasts on the soundtrack. The student paper of Central St. Martin’s, the art and design college located in the Coal Drops buildings, describes community-focused projects designed to draw attention to obesity, lack of safety, elderly people shut up in their flats alone, all around the college right now.

Around the corner one more turn and you come to Camley Street Natural Park. (Surely there are foxes here.) Through a back gate from an underpass is Old St. Pancras church, which has been a site of Christian worship since the fourth century. Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin were married here in 1796, when Wollstonecraft was already pregnant with the baby they both expected to be a son – Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, soon to be Shelley, who would know her mother only through words on a printed page, a portrait on a study-room wall, and the knowledge that giving birth to her had cost her mother’s life. The square stone marking the burial site of Wollstonecraft, Godwin, and “the second Mrs. Godwin,” Mary Jane Clairmont, still remains, although Mary Shelley’s daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Shelley – responsible for the weird, arresting Shelley memorial at Oxford, which says more about her than about Shelley himself – had the bodies of Wollstonecraft and Godwin moved to lie next to Mary Shelley in the churchyard at Bournemouth. No historical plaque is here. None’s needed. Crocuses thicken in the grass, bright white and golden and purple. In the trodden mud at the stone, there’s a faded cellophane-wrapped bouquet. Somebody’s planted cyclamen, too, below where Wollstonecraft’s inscription is still just visible. You can make a tracing on paper with a charcoal stick – Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, born 27 April 1759, died 10 September 1797 — or you can do as the young Mary Shelley herself is said to have done: crouched beside her mother’s grave, she ran her fingers over her mother’s name, and her own, learning the letters she would someday rearrange into a creature of her own.

Words and spirit and imagination and compassion and, in spite of all the evidence, hope for something beyond the world that we can see: these are our means of liberty and grace. They are our fuel. They have to be. Let’s power up.