Here at the hinge of old year and new, with books to promote and a new website underway, I’m wondering — again — about the relationship between writing and social media. It is what we need to communicate and self-present, to Get Ourselves Out There, no way to avoid it entirely. It does a lot of good in sharing news and concerns people need to share. But increasingly, in my own life, I ask about my own impulse to post to, say, Facebook: Why am I even doing this? Whose attention exactly am I trying to get, and why? Who can I trust out there to get what I mean in this meaning-distorting, corporatizing medium? Is anybody even really listening? Exactly what makes social media a fit for anything we need human emotion, or writing, to do and be right now? Isn’t it time we left this shit alone and worked out better ways to say what we actually feel? All of which are ways of saying, as a teacher and a writer, what is, and what will be, my work and mission in this world?

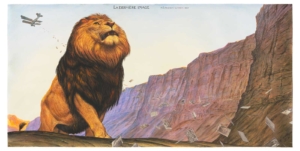

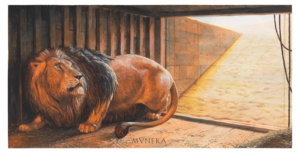

Here in the NY Review of Books blog is an article about the “21st-century naturalist” painter Walton Ford, b. 1960. Having nodded along with recent critiques of art-world trivia, I’m eager to see someone who can actually paint. And as the images unroll down my screen – a striding elephant enmeshed in a floating cloud (or Darwinian tangled bank) of beasts, an eagle coughing smoke – their rigorous beauty wallops me with grief. Most of all the lions. Most of all “Mvnera,” in which a lion cowers at what is obviously the upward-sloping entrance to the Colosseum. You can almost hear the chants and shouts in voices just as bloody and eager as our own. Lock her up. I’ve stood with my students in that great ruin on a chilly but still-too-warm January day, reading aloud Byron’s words from Childe Harold c. IV about the same decline we’re seeing now. We’ve watched pigeons perch between the paws of the great Landseer-sculpted beasts at the base of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square. Perhaps I will share this image with them when we go there again. Perhaps not. (More in a minute.)

Lions are important for Ford. Animals are important. Because of what they are and what they mean, regardless of how vexed human imputation of “meaning” can be. You can see it in the paintings, compelling and painful to look at as they must have been compelling and painful to paint, stroke by careful, classically trained stroke. And you can see the portal they open to the tremendous grief that is always backlighting our reality now. “When humans become stalker/lovers of a certain animal, that animal is screwed,” Ford has said. Look upon these creatures and the wave of guilt and sorrow rises: Look what we have done to those who could not resist us. Look what we have done, knowing that what we do is wrong.

Post this piece to Facebook, came the reflex. And then thought: why? What about this mix of emotions I have tried to describe right here will come through in a stupid blue-framed, striving-for-just-the-right-attention-catching-brevity window of someone’s downward-scrolling homepage? And my distaste spikes at the wheedling eager audience-pleasing I feel in myself, the automatic grooming of my first grief to Ford’s work down into something designed for maximum consumability by all my friends [I omit scare quotes because they are my friends.] It’s undignified, as the first response of grief itself is not. It feels fake. Look at the cool stuff I have curated and presented to the world with my superior taste. Give me a break. This is the response that rises in me now, and that feels right to pay attention to. There are writers who can still bring authentic and wonderful selves to the world in this medium, using social media for good; I’m eager to read what they have to say and proud to count them among my friends. But the risks and pitfalls and distortions of the medium increasingly feel too much for me. It’s trying to speak in a language that, like Orwell’s Newspeak, is always tugging what I actually feel toward a certain of-the-moment-approved glibness and fluency, just sharp enough to be interesting but just general enough to avoid Trouble. (And social media is excellent at bringing Trouble to the unwary or even the innocent, from any direction.) Seeing your own life in advance through other people’s imagined reactions is no way to live. Or to write, or to speak. Is this real language? Is this real writing? Is this honesty? No. So do you never say what you think? No. But you let yourself live in the privacy of your own thought, developing yourself into a self with something to say, before you choose the medium in which your self really can say what it wants.

Ford, like any artist, knows how framing something changes how we look at it and what we think it means. Social media frames things according to its own meanings and standards of “value,” meaning what sells ads, what alienates humans from their data, what boosts algorithms in particular directions. And, as it increasingly seems to me, what adds to the noise that blurs anything we feed it, hoping to be heard. What if we opt out. What if we call bullshit on social media’s false promises about itself and choose other ways of speaking and being in the world. What if we developed our thoughts in private and then chose how – or whether – to share them rather than tweeting ridiculous and disastrous self-contradictions or posting things to our “newsfeed” that will never go away, whether we change our minds about them or not. What if we chose not to play the game on the terms our social media overlords are presenting to us, for their own profit and our social and intellectual and moral impoverishment? Writers ourselves buy the hype a bit too easily. Jonathan Franzen, for instance, gets accused of not being able to “make a difference” because he’s not interested in social media. This seems to me to take social media’s values, and its self-assertion of them, a little too literally, while missing an opportunity for the kind of moral judgment writers do need to make about the world and how to speak to it.

Students – I believe and have seen – are waking up to this, because they will be dealing with it for longer than I will. They will have to find their own new ways to describe, and build more capacities to live in, their changed, and changing, world. And interestingly, some are also realizing that having been submerged in electronic norms means they’ll need to poke their heads back above that water to see reality – no matter how genuinely alarming that reality is. “Dr. Weldon,” a first-year student asked me suddenly in a conversation about income inequality in a story we’ve been reading, “what do you think the next crash will look like?” Not when the next crash will come. But what will it look like. The tinge of fear, but also the acceptance, in her voice set me back on my heels and made me ask, again, about my own teaching, what it means, why I’m doing this, whether I am giving students the tools they need for this world. They’ve never not known the Internet and, now, have never not known social media. (I taught my first college composition class as a graduate student in 1998 and have taught first-year college students every year of my life since then, so I’ve watched the changes unfold in speedy time-lapse, right in front of me.) I ask myself every day, What am I really doing? Why does it matter, and to whom? How can I bring some truth, light, clarity? How can I do and be better? What does it mean to be constructively countercultural, and to show others what that looks like? What must I resist? And how?

The questions invade and challenge me, limbering up something that likes to feel sure of itself. And I need to pay attention to that. Sure, I could just write all this in my journal, which is where it starts. Lots of things in journal and life never make it onto any public page; any writer knows that. But if you have a Ph.D and tenure and a voice you have a responsibility to try to use them well. Getting ready to teach for six months overseas amid Brexit and climate crisis has brought me sharply up against the fact that I need to push myself harder as a writer to be more direct, to speak, to speak to the moment, in a way that I actually can feel good about, and that other people can hear. Book projects are bumping at my mind like eager little boats tied to a dock – come on, step inside, push out into the water. I teach students to take risks. I need to do so too.

So that’s why I’m saying this in prose on a platform that at least somewhat feels like mine, and in books. They who have ears to hear, let them hear. The Lord God has given me the tongue of a teacher, that I may enlighten the weary with a word. We have to frame things for ourselves. We have to at least somewhat try to resist this meaningless noise of media that – it’s increasingly clear – were not actually built for us. Because the clock is running down on lies, and myths, but not on stories. There’s a difference. And in that difference lies an elusive and a saving thing.