“Is Facebook a monopoly?” is and is not the right question to ask. Here’s why.

Watching a batter-up rotation of senators take turns at questioning Mark Zuckerberg this week, and listening to the public response to the unfolding spectacle, shows three things very clearly:

1) As ever, law, ethics, and language lag far behind technology – defining “technology” as both our big-brain tool-making capacity and our new electronic consciousness-beasts. (What is Facebook, exactly? What is the type of social experience it creates? That shimmer of awareness-and-existence-in-the-minds-of-others that has even the freshly chagrined among us reluctant to deactivate our accounts now that Facebook has brought it into being – what is its name?)

2) MZ himself, while clearly worried about his company and doing his best to play along with The Law, doesn’t, at one level, understand what all the fuss is about. He had a cool idea and built a platform to actualize it. End of story. And yeah, to the tech brain at its purest, that really is all there is to it.

3) We ordinary non-techies who thought we were just signing onto a cool way to share baby pictures had no idea what we were getting into, and still don’t, not really – although, to be fair, the signs are and have been there all along. (“If the site is free,” Jaron Lanier has been warning for almost a decade, “then you are the product.”) We just don’t know how to look, or how to describe what we see, when we open the notification that our data has been shared with Cambridge Analytica or that we have been victims of a Russian-designed fake political ad or when we download all the information it has on us. We don’t know how to describe that particular feeling of having been complicit in our own betrayal.

All these, then, point me to a larger conclusion: As a society, we lack a shared moral language in which to even begin to think about what “technology” means, and in 2018, this indicates that we lack a shared moral language in which to think about our lives and what they mean. Stay with me for a minute. If we were connecting with and speaking with each other in person the way we might be, would Facebook still feel so necessary? If we felt a sense of purpose to our days, a sense of comfort with our own thoughts and capacities for thought, would we feel the need to reach for the phone during any idle moment, shopping for some new distraction in the newsfeed? Or, as Zadie Smith speculates in her great essay “Generation Why,” if we really wanted to keep up with all those people, wouldn’t we be doing so already? [Full disclosure: I’d be quitting this thing, too, if I didn’t have books to promote. But that’s a post for another day.]

The fact that we seem to be able to find no other language than the language of business — Is this a monopoly, Mr. Zuckerberg? Do you have competitors? How/should you be regulated? — is significant, and sad. Granted, that language can still feed Facebook into the legal mechanisms that are another social way of making statements about a common reality, and a common good. Problem is, business-speak can’t speak of everything there is that is worth speaking of. Tot up your expenditure’s on your child’s health care, education, clothing, books in terms of profit and loss and you see immediately the moral shortfall of such words. There is no way to say, literally, what a human life and the flourishing of a human spirit is worth, in financial terms. And that’s a good thing. Ditto natural resources – which is why trying to cast, say, the California redwoods into tourist dollars as a preservationist argument is a losing game.

I keep going back to the tone of bafflement in the voice of senator after senator (“so, Instagram…is that, would you say, a competitor? A product similar to yours?”), to the note of betrayal in the voice of the data-exposed users interviewed on the radio. And I go back to that silence that arises when we try to put a name to what it is that Facebook is and what it has been the means of stealing, is the means of stealing, from us. When I tried to name this thing myself, I ended up filling Chapter One of my book The Hands-On Life: How to Wake Yourself Up and Save The World (a digest of which you can read in this article here.) I ended up relying on literature, history, and philosophy to do it – a combination of Hannah Arendt’s working against cliché in order to set precise meaning, in language, to experience and George Orwell’s concept of “ownlife” from Nineteen Eighty-four, that space of utterly inviolable privacy within one’s head, which is the ultimate site of resistance to tyranny by the state or, in our own age, corporations. And, oh yeah, my faith, which has the temerity to argue that human beings are something more than wallets, or fingers on our smartphone screens.

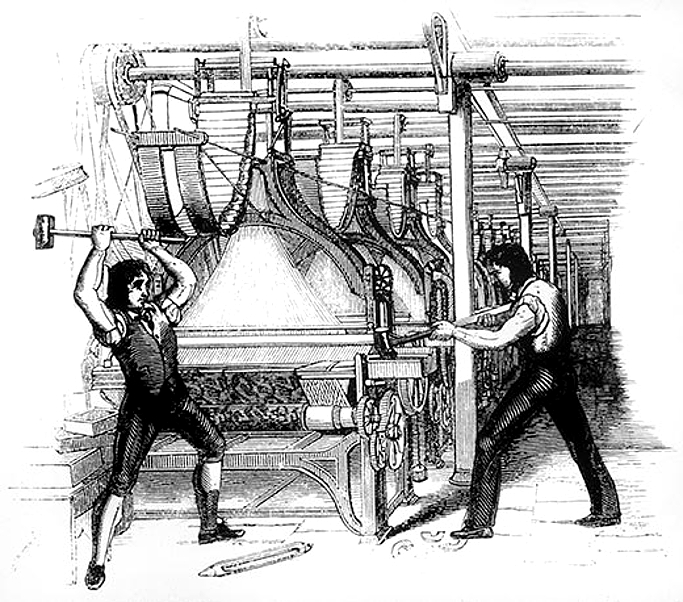

We must judge a technology, too, by what new crimes it makes possible. Consider the dispossession of the Nottinghamshire weavers who became the original Luddites, and whose machine-smashing Lord Byron defended in his maiden speech to the House of Lords in 1812. Those mechanized looms are recognizable forerunners of our self-driving cars and 3D printers. Today – as outlined indelibly by Rick Moody in the new issue of Harper’s – we struggle to deal with identity theft. (In a rhyming of art and life too good to invent, Moody argues with the thieves via text message during a meeting of his Dante study group.) Consider the name of that crime. Identity theft. To shrug and say, of this or anything connected with tech, “well, versions of this have always gone on” may be strictly true but abdicates our moral responsibility to name our new reality in order to understand it.

Being human beings, we have a great means of hope in our best creations: art, philosophy, theology, and language. These become even more important – as does the knowledge of our history – the farther into this weird future we go, and the more aggressively budget-cutting administrators attack these fields in our classrooms. (Maybe, just maybe, it might be nice to have some moral reasoning capacity in case your high-powered tech job lands you in front of a Congressional panel someday.) And therefore it is worth pressing ourselves to examine, very carefully, our impulse to sign on to our latest greatest “innovation” without examining and naming whether it is going to rob us of any, or all, of the things that make human a noble and important thing to be. As we watch the Facebook-in-Congress saga continue, we should consider this: Given the amount of agency we have ceded to this thing, our inability to name it, our silence in the face of it, should alarm us. Because it is worth taking note – very carefully – of what in human life or the natural world lies beyond the realm of the describable, and whether those things point to that which is life-sustaining (mystery, love, beauty, the vast web of ecology) or its opposite.

The Neanderthals swiftly tumbled to extinction 40,000 years ago when they encountered something they could not fully comprehend or even name: a humanoid species with the ability to think abstractly and express those thoughts symbolically. We are that specie. Now it’s our turn to be “out-competed.” By AI technology and patterns of thought we cannot comprehend or even name.

One hopes not…. although, yep, it’s on the way. Got to write a post soon about the AI creepiness of even the gentle little hybrid car – latest addition to the Luther fleet – I got to drive this weekend…