Hunkered on a funeral urn, he howls into the void. Howls? Is that mouth open or closed? Is that even a mouth? In the dim gallery, walls dappled all around with trees, I circle him like John Keats at the Grecian urn. We’re in this forest together now. Dug out of the earth in Spong Hill, Norfolk, he’s bottling sixteen hundred years of silence. The hands clapped over his ears – is that wonder or terror or rebellion? That flat-topped hat – is that a crown? The sinuous arms, out of proportion to the legs – is that just an early potter’s clumsiness or the kind of truth art gets at when it deliberately warps the world?

Edvard Munch set his own screaming man on a bridge in 1893, as the sunset blazed nuclear-bright and the twentieth century came barrelling down the tracks. Mummies in Parisian expositions and the medical museum of Florence – posed just like this Anglo-Saxon figure – could have been the inspiration for The Scream, but it’s not likely, or necessary. The Spong Hill artisan shaping this lid for his cremation jar wouldn’t have needed to look far, either, for a model. We all know what’s waiting in this forest. The body curls up and shrivels when it dies, and dries. In beds, in hospitals, even while breath still, technically, remains. Even before it’s lifted onto a pyre or wheeled into a furnace to become ashes in a silver jar or a hand-patted clay urn or a plastic bag inside a cardboard box.

The Anglo-Saxons as a people cohered out of migrants and movers more than a thousand years ago. Now, in 2019, Britain reckons with the end of empire and the uncertainty of Brexit. Here we are in the forest, staring into the void. What now? Death has altered the body of the country that said it wanted this: since 2016 three million elderly have died, three million young come onto the rolls. Breakaway moderate MPs are forming a new independent party. Labour and Tories, said one, are parties for the society of twenty years ago – we need a party for the society we have now. If a referendum were held today, Leave would probably not win. Why, many ask, should we be bound by the wishes of the dead? “Disrespectful,” tweets the home secretary in response. Half-serious, half-satirical, a new boy band weighs in: “Britain Come Back.” Brexit is rising up to strain and crack business- and politics-as-usual like a tree root from underneath a sidewalk, like gravestones tipped in a frost-heave. But non-Brexit crisis can’t wait. Schoolchildren go on strike for climate action, following the example of sixteen-year-old Greta Thurnberg, who challenged the bigwigs of Davos to wake up to the climate emergency she’ll be living with a lot longer than they will. As the legal net tightens around our sitting US President, he flails and flings base-appeasement bones by appointing a panel to “study” if – if – climate change presents a national-security threat. The world trundles toward a void of ecological disaster and the political stasis and human obstinance that’ll send us over that edge. And, here in the British Library, treasure house of this country I do love, I think about the future and what literature has to do with it, how we can truly respect the dead and build a world that can sustain the living.

One answer comes from a woman few of us know: Anna Letitia Barbauld (1743-1825), wife and daughter of Dissenting schoolmasters, earnest 18th-century antislavery liberal, writer for children, tagged as the prude who complained to Coleridge that the Rime of the Ancient Mariner “had no moral.” In silhouette she’s either a generic 18th-century poetess or an old lady in a ruffled mobcap whose indented chin betrays a loss of teeth. Yet there’s more to her. Married to a man who went mad and at one point attacked her with a knife, she had to leap out of a window to escape him. Watching the world around her descending into war, she decided to write about it. Which means that she was not just a “poetess” – she was a prophet.

*

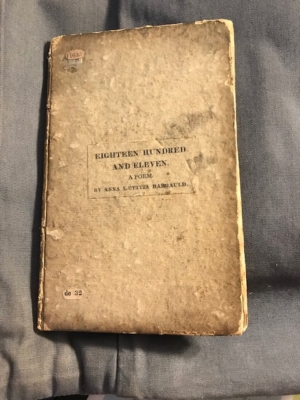

Eighteen Hundred and Eleven: A Poem comes to me in a pale envelope labeled in pencil with its shelf number and stamped in green ink BRITISH LIBRARY UNBOUND PAMPHLET BOOKS. When I slide out the dark-discolored mottled small pamphlet and turn it over, it takes me a minute to realize what I’m holding: the poem itself, ALB’s epic and prophecy. This is a first American edition from the London one, dated 1812. Here it begins:

Still the loud death drum, thundering from afar,

O’er the vext nations pours the storm of war:

To the stern call still Britain bends her ear,

Feeds the fierce strife, the alternate hope and fear;

Bravely, though vainly, dares to strive with Fate,

And seeks by turns to prop each sinking state.

These words are written as Britain has already been at war with France for more than a decade, and the pain is biting deep. Jenny Uglow in In These Times writes about the domestic effects of the Napoleonic Wars as press-gangs and PTSD come home and the country struggles to supply the needs of soldiers and civilians. Barbauld homes in on them too: in the fields of England, Nature offers her usual gifts but is ignored as nation chooses war and soldiers scratching for food clash with the farmers growing that food for their own families. The scene recalls Adam Nicolson’s description of medieval English peasant life in Quarrel with the King: it was so tightly regulated because it had so many people to support and resources were so relatively precarious – the balance could be upset by unusual stress, by one person breaking the rules.

Bounteous in vain, with frantic man at strife,

Glad Nature pours the means – the joys of life;

In vain with orange blossoms scents the gale,

The hills with olives clothes, with corn the vale;

Man calls to Famine, nor invokes in vain,

Disease and Rapine follow in her train;

The tramp of marching hosts disturbs the plough,

The sword, not sickle, reaps the harvest now;

And where the Soldier gleans the scant supply,

The helpless Peasant but retires to die;

No laws his hut from licensed outrage shield,

And war’s least horror is the ensanguined field.

This is ecology’s first lesson: There is no away. There is no safely other, distant place where what we do only affects them, not us. Actions have consequences. War comes home. If Britain keeps going on its self-imposed decline, Barbauld has a vision of how that might look: ruins haunted by dreams of former glory and culture.

Now hears the shriek of wo – or Freedom’s knell:

Perhaps, she says, long ages past away,

And set in western waves our closing day,

Night, Gothic night, again may shade the plains

Where Power is seated, and where Science reigns;

England, the seat of arts, be only known

By the gray ruin and the mouldering stone;

That Time may tear the garland from her brow,

And Europe sit in dust, as Asia now.

The twentieth-century English poet Philip Larkin famously speculated that perhaps “what will survive of us is love.” What will survive of Britain – or any country – in apocalypse? For Barbauld, the answer is culture: names for new generations of poets and thinkers in other lands to muse on and yearn toward just as I yearn toward them now. Milton will still be a name to conjure with – so will “Old Father Thames.” Wordsworthianly, they will be inner sources of meaning and motivation that will help new eyes see past the surface of an apparently deserted place – even the ruins of London itself, a city once open and cosmopolitan:

But who their mingled feelings shall pursue

When London’s faded glories rise to view?

The mighty city, which by every road,

In floods of people poured itself abroad;

Ungirt by walls, irregularly great,

No jealous drawbridge, and no closing gate;

Whose merchants (such the state which commerce brings)

Sent forth their mandates to dependant kings;

Streets, where the turban’d Moslem, bearded Jew,

And woolly Afric, met the brown Hindu;

Where through each vein spontaneous plenty flowed,

Where Wealth enjoyed, and Charity bestowed.

Pensive and thoughtful shall the wanderers greet

Each splendid square, and still, untrodden street;

Or of some crumbling turret, mined by time,

The broken stair with perilous step shall climb,

Thence stretch their view the wide horizon round,

By scattered hamlets trace its antient bound,

And, choked no more with fleets, fair Thames survey

Through reeds and sedge pursue his idle way.

With throbbing bosoms shall the wanderers tread

The hallowed mansions of the silent dead,

Shall enter the long isle and vaulted dome

Where Genius and where Valour find a home;

Awe-struck, midst chill sepulchral marbles breathe,

Where all above is still, as all beneath;

Bend at each antique shrine, and frequent turn

To clasp with fond delight some sculptured urn,

The ponderous mass of Johnson’s form to greet,

Or breathe the prayer at Howard’s sainted feet.

Yet all isn’t stasis and death. A spirit still walks over the land like some green man or Blakean giant, a spirit of greatness and generosity and innovation that is sustainable and life-giving. Barbauld admits the possibility that this spirit may walk over Britain and keep on walking – to Ireland.

And now, where Caesar saw with proud disdain

The wattled hut and skin of azure stain,

Corinthian columns rear their graceful forms,

And light varandas brave the wintry storms,

While British tongues the fading fame prolong

Of Tully’s eloquence and Maro’s song.

Where once Bonduca whirled the scythed car,

And the fierce matrons raised the shriek of war,

Light forms beneath transparent muslins float,

And tutored voices swell the artful note.

The reference to Queen Boudicca (“Bonduca”) here, whose statue rises at the foot of Westminster Bridge to symbolize native resistance to Roman rule, points to the intertwined fates of Britain and Ireland. Once exploited, then feared, Ireland, as Barbauld signals here, could yet become a symbol of modernity and civilization. (In the person of Fintan O’Toole, it’s also given us a brilliant Brexit-analyzer.) Ireland’s been held up as a potential model of what Britain could be: a stable, thriving country with its own rich traditions yet successfully overcoming the worst of its history to remain allied with the EU and ease the movement of ideas and people (especially young people.) Barbauld’s vision shades into today: the Celtic Tiger will purr, twitching its tail in contentment, while the British Lion couches on its plinth, lonely, immobile, the space between its paws empty except for the occasional pigeon or tourist scrambling up to get a picture snapped to post to social media – Look! Here I am in England™! – and scrambling down again and moving on. Ultimately, though, America’s the ultimate destination of this roving creative spirit. “Thy world, Columbus, shall be free!” Barbauld proclaims at the poem’s end. A few years later, Byron “stand[s] on the Bridge of Sighs, a palace and a prison on each hand,” wondering, just as Barbauld does, how the rise and fall of the Venetian empire might predict his own country’s future. It’s a vision with a touch of sadness – culture as consolation prize when everything else is gone, tourism as self-commodification, a restless selfie-driven “authenticity” hunt struggled-with also in Venice and American wilderness right now. But something of real value lies in it, too.

*

Gazing at Spong Man just as Keats gazed at the Parthenon frieze and his Grecian urn, we can ask: what will survive of us? If we are coming to the end of something in country after country all over the world, and if we are to use resources well and resist fantasies of violence and homegrown extremism, what can we build instead? How can we be life-affirming rather than death-dealing? And how can we as citizens hold our leaders and ourselves to account in asking for something better, something worthy of the human spirit at its best? I find a practical solution in the breakaway coalition of newly “independent” Tories and Labourers, crossing the aisle in the name of a vision of the common good. I find an even greater hope in history and literature, which expand our capacities (a significant word) for curiosity and empathy and our abilities to hold ourselves to account. Art, history, literature, culture tells us that our present needs in this present moment aren’t all there is. That there is and always has been more to reality than the ravenous selfish self. That mortality is coming to all of us, so we’d better build something healthy in our time on earth, and leave this earth better than we found it.