“It’s a matter of common decency. That’s an idea which may make some people smile, but the only means of fighting a plague is — common decency.” Albert Camus, The Plague

Read War and Peace in a free virtual book club with the writer Yiyun Li. From A Public Space.

Free virtual book clubs and other events are forthcoming at Emergence Magazine.

Watch the Metropolitan Opera for free!

Well, my sabbatical trip is off. So is Stephen Greenblatt’s. Writing on his plane back from Rome, he describes “the marked presence of the warmth and kindness that make ordinary life here so agreeable, notwithstanding the country’s notorious political dysfunction. It is as if people instinctively sense, even as their anxiety levels rise and their economy sinks, that their version of social order rests on good humor, patience, inventiveness, and flexibility.” Two months ago, students and I were in Italy too. Now my Venetian friend says he’s never seen the lagoon in front of St. Mark’s so still. The canals are clearing, too – and there are fish! Yet the news from Italian hospitals is heartbreaking. This frontline report from respiratory unit chief Dr. Fabiano DiMarco of Bergamo shows clearly what’s at stake.

I originally planned to depart for London on March 15 and stay until April 5. As recently as Sunday, March 8th [only 11 days ago?!], I still hoped to proceed, trusting handwashing and the NHS. Yet by Wednesday the 11th things had exploded, and, afraid of being stranded, I canceled my trip. On March 18, according to Johns Hopkins’ tracker, the US has had 7,769 confirmed cases of coronavirus and the UK 2,642. Europe is closing borders and the outbreak’s epicenter has moved from China to Italy. Schools and bars and libraries (including the British Library’s reading room, where I’d planned to spend most of my trip) are closed. Thousands of workers are in economic pain. Streets are empty from New York to San Francisco. On March 16, the US stock market had its worst daily decline since 1987. Idris Elba has joined Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson on the list of celebrities who have the virus. Colleges are sending students home at least through April. Congress is weighing a $1 trillion economic stimulus. Restaurants are closing to all but takeout. Doctors and nurses are doing heroic work. And the rest of us are social distancing and staying home.

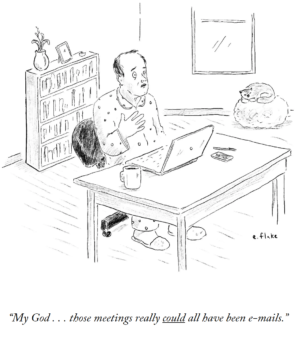

So, I’m an English professor on sabbatical staycation at my desk. How do I get a grip on all this? Especially as so many people seek to survive economically, psychologically, physically, and spiritually? I can write at my desk at home; teaching online – which my brave colleagues are ramping up to do – is much more difficult. To say nothing of being a health care worker, or a restaurant worker facing layoffs, or one of the grocery store cashiers who are helping keep the doors open at our local store. In canceling my international flight I’ve just done as much good for the climate as eight years of recycling. How am I helping to build human capacities to live in a world where global disruptions and uncertainties aren’t going to go away? So here’s an attempt to get a grip on some things that seem clearer as we plan to come out on the other side of this – and as the Presidential election approaches.

We’ve got to secure the local, even in a global economy. One year ago right now, I was in London wondering whether my students and I should buy an extra week of groceries. What would happen to the lorries lined up at Dover if Brexit went ahead? How many small farms were there in the UK, and what could they produce? “British Beef” packages in Waitrose: yes. Spanish oranges: not so much.

Those weeks of pre-Brexit nervousness turned out to be something of a preview. Grocery suppliers have reassured anxious shoppers that despite empty toilet-paper shelves “there’s still plenty of food.” Here in northeast Iowa, we have a local food economy defining “local” as produced within a hundred miles, including meat here and here and dairy here, and our great co-op, which is able to draw from multiple suppliers (and has now shifted to curbside pickup service.) This takes a lot of work and a lot of conscious support from city councilors and consumers. Yet even this ecosystem can be disrupted by global climate change: floods that wipe out a whole crop, droughts that shrivel it, late snows or frosts. As the old bumper sticker asked, “’Throw it away’ – where’s ‘away?’” On and off our screens, the world and its challenges are looking more similar these days: there isn’t really an “away,” although there’s definitely still a “here.” Urban farming and local food systems of many sorts offer so many practical benefits, including real hope, security, and community resilience. Let’s invest in them.

Chronic underinvestment in education and research metastasizes, in unexpected forms. Here’s a thoughtful interview with Dr. Rupert Beale of London’s Francis Crick Institute, author of this great piece on coronavirus biology. He reminds us that only long-term investment enables long-term projects like vaccine. CDC budget cuts come home to roost. Just like higher education in general, or old-growth forests, research apparati are ecosystems that take years to grow and days to destroy. We need systematic training in fields of knowledge and the critical thinking to make good use of them. Otherwise, we’re left with truculent incuriosity and deliberate anti-intellectualism, both of which are fatal. (No, drinking bleach or snorting coke won’t kill coronavirus.) Alone in our heads with our screens, we need some good companions: history, literature, science, the communal voices of the present and the past. Education introduces us to them, and keeps them in our lives to walk beside us, even in times of uncertainty and fear.

Our health care system is driven by insurance- and drug-company CEOs, not nurses and doctors. It was a sad day when my late father, dispirited by his increasingly corporate medical field, confessed he could no longer encourage his children to follow him. Blessedly, I still have brilliant students who graduate from Luther into medical school and the Mayo Clinic’s cardiac nursing team. (Luther has also been proud of our graduate and onetime Regent Mike Osterholm.) But as in law and academia, profit-driven centralizations and precarities are making things much harder for their generation than it was for my father’s, or mine. It doesn’t help that even before the coronavirus crisis and the mass aging of boomers, geriatrics, public health, and infectious disease aren’t the sexiest or richest fields. Nor that, in spite of everything, some people still seek profit first.

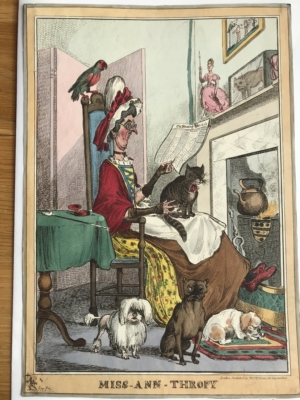

Misled by tech mythology, we’re losing sight of what entrepreneurship, work, and opportunity actually look like – and how to bring them back within reach. Consider the Tennessee price-gouger who bought up 17,770 bottles of hand sanitizer from every discount store in range, then stockpiled them to sell at a markup on Amazon before being ordered by the law (and public outrage) to donate them. Where to begin with this guy? Maybe just here: “a former Air Force technical sergeant” who posed for the New York Times wearing a t-shirt that says Family Man, Family Business can’t see that his “family business” is a little parasite on two corporate-welfare beasts: discount stores and Amazon.com. He’s not “adding value” or “correcting an inefficiency” – he’s busting in on an existing supply chain, with potentially fatal results.

This can’t be unrelated to the way “entrepreneur” has come to be synonymous with “app builder,” although the entrepreneurs I know run cattle farms, bookstores, clothing shops, insurance agencies, the garage that coddles my 15-year-old car (thank you, Jeff!), and a taxi service that helps elderly people stay independent. Yet opportunities for this kind of on-the-ground doing and building are shrinking – thus the “deaths of despair” that follow automation, the false promises of the gig economy, and the anger of my students graduating into fewer prospects than their parents. Healthy economies glow with the firefly lights of small businesses, who strengthen and dignify local life as they weave together responsibility, risk, and reward every day. Our government, and each of us, need to support them, not just the airlines.

What our screen-centered world actually does to us far outruns our ability to understand and respond constructively to what it does. The Internet’s keeping lots of us in work and school and even more of us from going stir-crazy at home. It’s a necessary tool. But it heightens the risks of a nervous time. Carl Miller, research director of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media (CASM) at Demos, has a thoughtful discussion of this on the March 14 “Another Europe is Possible” podcast. “Information is at its most dangerous just when it’s also at its most important,” he says. “Epidemics and infodemics go hand in hand every time.” Yet, he says, “We’re not the victims in all of these infodemics – we’re a kind of willing prey.” Transcribed from the podcast, here are his “Seven Rules of Digital Hygiene:”

- “The information that wants to find you isn’t the information you want to find. Actively look for the information you want; don’t let it find you wherever you are on the internet. Be active, not passive.”

- “Beware the passive scroll – this is when you’re prey to all the processes that can be gamed, the virals that can be shaped, the ways in which the online world can be manipulated to find you and to reach you.”

- “Outrage is your biggest vulnerability to being manipulated online… It’s always easy to fire, it usually spurs activity online, and it really helpfully makes the person on the [opposing social/political side] outraged too.”

- “Slow down. Pause before sharing. Give time for your rational thought processes to engage with what you’re reading.”

- “Lean away from all the metrics that can be spoofed. Don’t trust something just because it’s popular, trending, or visible.”

- “On key pieces of information – health and diagnosis, of course, but also, say, where to vote – never just rely on information sourced from social media. Phone someone. Look at offline cases too. Triangulate analog and digital worlds together. And the golden rule…”

- “Your attention is now both your most precious and coveted asset and also something which can harm you. Spend it wisely. Think of your information diet like your diet; it has health consequences for you and the people around you, especially in infodemics. It’s time to think about this.”

In newly and oddly opened mental space, let’s not freak out – let’s try to think. “To see what is in front of your nose,” wrote George Orwell, “requires a constant struggle.” Thinking is a vital action in “dark times,” as testified by Hannah Arendt, Jewish survivor of the Holocaust and badass philosopher. Writing in 1971 about the Pentagon Papers, Arendt says that especially in crisis, a society needs a common understanding of reality and fact, which can be deliberately endangered by politicians but preserved by historians and journalists:

“Without the mental freedom to deny or affirm existence, to say “yes” or “no”—not just to statements or propositions in order to express agreement or disagreement, but to things as they are given, beyond agreement or disagreement, to our organs of perception and cognition—no action would be possible; and action is of course the very stuff politics is made of.3

Hence, when we talk about lying, and especially about lying among acting men, let us remember that the lie did not creep into politics by some accident of human sinfulness; moral outrage, for this reason alone, is not likely to make it disappear. […] The historian knows how vulnerable is the whole texture of facts in which we spend our daily lives; it is always in danger of being perforated by single lies or torn to shreds by the organized lying of groups, nations, or classes, or denied and distorted, often carefully covered up by reams of falsehoods or simply allowed to fall into oblivion. Facts need testimony to be remembered and trustworthy witnesses to be established in order to find a secure dwelling place in the domain of human affairs. From this, it follows that no factual statement can ever be beyond doubt—as secure and shielded against attack as, for instance, the statement that two and two make four.

It is this fragility that makes deception so easy up to a point, and so tempting. It never comes into a conflict with reason, because things could indeed have been as the liar maintains they were; lies are often much more plausible, more appealing to reason, than reality, since the liar has the great advantage of knowing beforehand what the audience wishes or expects to hear. He has prepared his story for public consumption with a careful eye to making it credible, whereas reality has the disconcerting habit of confronting us with the unexpected for which we were not prepared.”

Watching #45 assert that he never downplayed the severity of the coronavirus pandemic reminds me not only of Arendt’s analysis above but of the slippery horror of Winston Smith in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four, trying to keep a grip on historical memory and fact as Big Brother insists that two and two make five. This is why we need historians, and scientists, and facts, and evidence. This is why we need journalists. This is why we need writers.

I’m not alone in wondering whether these days are a test for what we will need to get through the big uncertainties of the twenty-first century, particularly the climate crisis – especially living with limitations on travel and learning how to supply our basic needs in our own communities. We’re trying to keep our minds and spirits active, forward-going, and thoughtful – reaching out to others, reading books, going for walks — when our usual sources of support have been removed So what’s the work of the humanities now? Like prophets and storytellers in any time: to bring the good news, the wider view, the unexpected connections. To open doors we don’t usually see, and encourage people to look through. To offer mental companionship to people you may never meet. Adrienne Rich wrote poems “for the relief of the body / and the reconstruction of the mind.” William Carlos Williams wrote that “it is difficult to get the news from poetry / yet men die every day / for lack of what is found there.” Writers build books in the hope they will be found by people who need them, now and in a future we can’t see. Teachers try to build people themselves – or rather the foundations for the kind of resilient and curious selves who can keep going amid uncertainty. You need good companions in your mind with you, throughout your life, because you never know what’s coming next.

A few days ago, I fell into an email conversation with a former student – now a graduate student in theology on the East Coast – that became a Skype conversation just like the ones we used to have in my office, hanging out, talking about books and everything from roommate dilemmas to faith. The student and I ended up talking for two hours online about the coronavirus situation and what is very clearly his vocation: ministering to the needs of the world by fostering conversation among people about the divine and between people and the divine. He told me about his course in “practical theology” and his routines with his housemates. It was clear to me that he has continued to grow into a thoughtful adult, beyond me, into a life and mission of his own. I couldn’t be prouder of him. Relief, reconstruction and even resurrection of the mind – that’s education, and mentorship, and friendship.

In May 1818, the apprentice poet and until-recently-medical-student John Keats mused about how to get through what sounds like a description of an anxiety attack right now. “The difference of high Sensations with and without knowledge,” he wrote, “appears to me this – in the latter case we are falling continually ten thousand fathoms deep and being blown up again without wings and with all [the] horror of a bare shouldered Creature – in the former case, our shoulders are fledged, and we go thro’ the same air and space without fear.”

Companioned in his own short life by Milton and Shakespeare, Keats has become an imaginative companion for my students, and for me. This image is borrowed from Paradise Lost; the rebel angel tumbles through space, buffeted by terror and anger, unable to arrest his fall. Yet when knowledge or insight or perspective arrives – when we have that sudden moment of clarity or realization – it’s as if wings sprout from our shoulders and break our fall. And then, with our own wings, under our own strength, we can reverse the direction of fall, and we can rise.