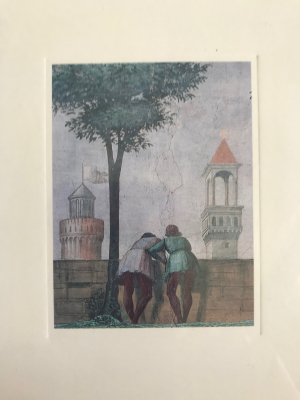

Two men in tunics and hose, their backs to me, lean on the wall of a castle balcony and look down at something happening on the other side. A slim tree leafs out elegantly to the left. They’re relaxed, intent, faces totally hidden. What’s going on down there, in this picture’s entirely private world?

Framed by a wide white border, this image floats on a four-by-six-inch paper card. I’ve had it for almost thirty years. I got it when I was about my students’ age, although I don’t remember when or where, and I didn’t know, then, the name of the artist or anything else about it. But I do remember the spike of curiosity and longing that pierced me when I saw it, as art can pierce you with the discovery of your own emotions, especially when your age begins with a 1 or a 2. I bought that card and kept it because I had to have this picture. I had to hold it to myself to be able to study the beauty of this new thing I didn’t know how to describe.

Beauty was a pursuit for me already, although I wouldn’t have given it that name. Tall and sturdy-limbed and bookish and freakish, I grew up in Alabama loving what would love me back – parents and books and animals – and hating what mocked, the other kids at school and the random men who’d murmur shit, that little girl’s as tall as a man and even the teachers who’d laugh incredulously when I reported that I’d finished my homework already, yes, and tomorrow’s homework too, so could I read now? In fifth grade the teacher confiscated my library book, the Silver Chair volume of the Chronicles of Narnia, in the middle of class. I still remember my helpless fury as I stared at the mustard-yellow cover resting in the rack under her seat as she sat in front of us no doubt teaching something useful, trying to ignore what I was sure was the other kids’ gloating, my head full as a wineskin with that vivid world and its strange creatures and its pleasurable sounds: Marsh-wiggle. Puddle-glum. Caspian.

The obvious move would’ve been to cast myself simply as misunderstood provincial, waiting to shake off the dust and get the hell out. But books were only one route to the larger thing living under the surface of the world around me and occasionally visible through it; to fail to love the land around me was to fail to love it, too. Beauty is a word for it; so is the past; so is mystery; so is fantasy or dream, although those two words have a frivolous edge that this shimmering, forlorn, wounded thing lacked. It lived in the corners of our old barn’s hayloft and in the ruins of sharecroppers’ cabins, islanded now in sedge grass and what would, in a few more years, be seedling pines. It lived in the silvery-white wild lilies that came up in a marshy little spot in the woods every spring. I could hear it in the Methodist hymns we sang every Sunday and smell it in the rueful woodsmoke chill of early fall. It lived in dangerous things, too: raised voices, veiled glances, my grandfather’s cane, raised in a swirl of red dust, as he beat to death a copperhead crossing the road in front of his car. Spirit of place might seem like another word, now, but maybe it is really the spirit of time I’m trying to name. Maybe it’s the heart-catching paradox that comes with an awareness of ourselves in time: we are here in a beautiful world, continually stumbling over beauty we did not make and cruelty in which we’re always already involved because we’re human beings and human beings are fallen things no matter how we try to raise ourselves up, standing in the need of prayer and grace we can never quite deserve for all our sins known and unknown, things done and left undone.

We act upon the world and it acts on us. Climate and ecology make this visible now: dolphins stranded in the streets of a hurricane-flooded coastal town, whales driven mad by sonar testing, oceans seeded with plastic bits worn smaller and smaller but never worn away. So do the bodies of the homeless, the people Jesus loved in poet Marie Howe’s words, bowing on subway platforms and street corners, human flesh vulnerable and broken. And so – blessedly, titanically – does art, asking in a language entirely its own, do you want to look again at this, do you want to see more than you think possible right now, do you want to be redeemed?

Now I’m a teacher myself. Classroom distractions have screens, not pages. I’m too far away from Alabama to know for sure whether the lilies still bloom up there in the woods. My students move with apparent nonchalance among words I’d never heard of at their age: global economic inequality, climate change, election fraud, terrorism. The world washes over them, magnified and muted by text messages and instantly shared photos and omg did you see this? Sometime in the twenty-first century’s second decade, a student approaches, slightly embarrassed: Can you read me this comment that you wrote? I don’t, well, I don’t read much handwriting anymore.

In January 2015, I take students on a study-abroad course on the Keats-Shelley circle, starting in London and continuing through Geneva and Italy. We land in London on the morning that two terrorists shoot up the offices of the magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris, killing twelve people and injuring eleven. Rallies in support of free speech and art erupt all over the world. Pro-Charlie symbols fill Trafalgar Square: fliers taped to the pavement, plastic bins of pencils and pens. Hundreds of pencils and pens.

By the time we get to Florence, three cities later, the leeriness and shock have worn off a little, but a certain melancholy remains. We’ve been through Venice, jaw-droppingly beautiful and sad, swarmed by the global rich with Gucci bags, selfie-ing in front of St. Mark’s. For the first time I seek out Torcello, the oldest inhabited island in the lagoon, and felt there the same spirits as in the woods and fields of childhood, mixed with something stern and bracing that lives in the face of the mosaiced Virgin on the wall of its Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta, musing and private and demanding. The first church here was built in 639. Almost no other tourists are on the island at all. There are stray cats, artichoke fields, a man trimming the cedar trees around his olive grove with a pole saw just like my father’s, back in Alabama. In a tiny antique shop an old lady sits smoking, smiling at me as I lift from its tray the most beautiful necklace I’ve ever seen: a honey-colored stone in a silver net, suspended from a string of tiger’s-eye beads. Nineteenth century, carnelian. I pay for it and clasp it on instantly and it rides back across the lagoon with me on the grumbling shuttle boat, the sun setting, teenagers nuzzling and chatting, small children asleep, Burano-sated tourists becalmed in their seats. The lady from the antique shop is up in front to the left, reading a newspaper, back in a world that doesn’t need to include me anymore.

Florence is beautiful, and armed. Chiseled soldiers in red berets hoist assault rifles in front of the Duomo. Roma women of indeterminate age, bodies swollen with time and disease, huddle face-down on the pavement, hands lifted in supplication, murmuring almost inaudibly povere, povere. We visit the Uffizi and the Accademia and Dante’s house and on impulse I take the students across the wide piazza into the church of Santa Maria Novella, scrambling to marshal the historical knowledge that masses so effortlessly in my mind when I’m reading at home and scatters, cowed and awed, once I stand in front of the real thing.

Like the Duomo’s, Santa Maria Novella’s facade is pink and white and green, native Tuscan marble like that supposedly absorbed by Michelangelo as dust on the nipple of his wet nurse, a stonemason’s wife. Something about this stone does absorb light and attention and a particular rapt wonder, then gives it back as an invitation to admire and to come inside. Like my Venetian carnelian stone, it wants to be touched. It’s human by inclination and design. It’s bodily, from the earth’s own veins. And when a well-off merchant and banker named Giovanni Tornabuoni commissioned frescoes of the life of the Virgin Mary and the life of John the Baptist for the main chapel, with himself and his wife in the bottom corners as two praying supplicants, Michelangelo was part of the team that painted them.

The most powerful man in Florence at that time was Tornabuoni’s nephew Lorenzo de Medici, who survived an assassination attempt on Easter Sunday in the Duomo itself and whose sharp-nosed, dark face usually gets called ugly by historians but looks fascinating to me: clever, humorous, undeceived. Unlike lots of rich people, Lorenzo had real taste, and knew real talent: he picked up on the fourteen-year-old Michelangelo and brought him to live in his house. He must have said to the chief artist, Ghirlandaio, when the frescoes in Santa Maria Novella got underway in 1485, Hey, Domenico, my friend. This boy here, give him a chance. You won’t be disappointed. So a teenage Michelangelo would have been one of the crew hammering scaffolds and mixing the plaster to spread in the measure of each day’s work, the giornato, itself named after a day, the three-feet-square patch you can complete while the surface is still at the right consistency, delicate and tensile as the skin on top of a pudding, just able to absorb the color and lock it in as it dries to the dusty, radiant blues and greens and cinnamons and brocades of gowns and skies and bedchambers, to the clear skin tones of faces and reserved, resigned gazes, one of which is the artist himself, turning to stare arrestingly at me as I climb the steps behind the altar and stare, dazzled, at the tiers of figures rising to the ceiling.

I turn to the opposite wall, where Mary meets Elizabeth, surrounded by graceful women in Renaissance dress and flowing robes and, in the distance, one ordinary woman hustling along with a tray of bread. The sky is cloudy and elegant, grayish-blue, pierced by towers in the distance. And there in the background – a deceptively casual shock that swells in my brain, disbelieving – are the two men from my long-treasured picture card, looking over the wall, lost in their own secret world that neither I nor the woman can see. They are here. I have walked into this church unknowing and found them waiting for me.

By the following year, I’ve become able to describe this moment to a new group of students when I bring them to this spot. See those two men there, right up there? I saw a card with their picture when I was your age, even younger, and something about it fascinated me, so I kept it. All these years, I kept it. The world will be bigger, it seemed to say. There is more out there, waiting. And last year when I walked into this church, there they were. Here you are, now, too, in one of the greatest cities in the world, seeing and growing and changing so much, with more to come. The world is larger now, the world will be larger. This is what travel does. This is what art does. Isn’t it wonderful?

At the end of the trip, students give me a gift: a postcard bought in Santa Maria Novella of those same two men, covered with handwritten notes from each student. Thank you for enlarging our worlds, and for sharing your world with us.

In January 2018, the world feels freshly vulnerable and broken. An overwhelmingly popular American president has been succeeded by an overwhelmingly unpopular one who seems intent on earning that reaction in new ways every day. Britain has voted to leave the EU even though the most popular Google search, the day after the vote, was “What is the EU?” Racism seeps like poison gas up through a welter of plain bafflement, at home and abroad. They’re coming in, taking our jobs. We’ve got to make our country great again. What are we going to do with all these people? Historians and spin doctors battle for a distracted public’s attention with arguments about documentary evidence and deleted tweets and alternative facts. At lunch in a friend’s home on the outskirts of London, students and I sit, barely daring to breathe, as our friend begins reminiscing about his childhood memories of the Blitz. My father was a safety patroller; he’d come home in the mornings dead tired and go right to sleep. I remember the sound the bombs made when they came in. A screaming noise. We can see the thoughts well up inside him, shading the surface of his face. He doesn’t talk about them for long.

I ask my friend’s opinion about something I’ve noticed on successive visits to London. In 2013, students and I discovered a former air-raid shelter in the basement of the Methodist Central Hall near Westminster Abbey, which was marked with interpretive signs and vintage propaganda posters and photos. By 2016, the space had been remodeled as a conference center, slickly dressed in fresh paint and white crown molding, and all those signs were gone. And on this trip, in 2018, the only proof of its history is me, an American professor standing there describing it to students as faintly curious people in suits stride past. “Well,” says my friend ironically, “they do get lots of German visitors through there…”

My friend is not entirely dismayed by Brexit, and, although I am, I think I see why he feels this way. If you have watched your past – the physical and social textures of experience in your place – being smudged away by global capitalist partnerships and tax-shelter homes for billionaires and profit-making (which all of us are watching, now, one way or another), it is right and proper to object to that. It’s good to hearken to that feeling in your gut that says this is wrong. It’s good to ask of the world, and of ourselves, responsibility to something beyond our own needs in this moment right now. It leads us to responsibility to those who share the world with us: living and dead, human and non-. Physical objects make a claim on us as physical bodies do. Not for nothing did George Orwell write about Winston Smith holding the photograph of Rutherford, Jones, and Aaronson in his hands, absorbing the proof that these official nonpersons had ever existed, before dropping it obediently down the memory hole. On our first day in London, one of my students, distressed by Donald Trump and alternative facts, buys a book called Orwell on Truth and carries it in his backpack all month. Our trip would not have been the same, he tells me later, without that book right by his side.

At the Acqua Alta bookshop, Venice

Preserving the texture of human experience in places, and our ability to recognize it, means preserving our humanity. On our trips, students and I find the truth of this: praying in Italian churches, rapt in front of works of art, frozen in place by some felt spirit of the past, forlorn and endangered, begging to be noticed and saved in a world bent only on profit. Students look closely. They stand soberly at the graves of Mary Wollstonecraft and John Keats, wiping away surreptitious tears. They write in their journals at any opportunity: in subway cars, hunkered on park benches and statue pedestals and city curbs. They talk to other students in the hostel lounge and to elders and guides. They’re seeing and thinking about a lot.

And the world gives back to them. At the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, four young men with trumpets, tuba, and trombone are practicing a mournful tune just across the lawn from Keats’ grave. Clearing their throats, two of my young male students read the words of the young man who lies under the earth at our feet. When I have fears that I may cease to be…. Beauty is truth, truth beauty. That is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. I start to read “This living hand” – my favorite – and am choked by tears. “Well, y’all,” I finally say, “let’s just listen to the music. Keats would have loved a jazz funeral.” And at that moment, the band springs into “When the Saints Go Marching In.” It’s joyous and sad and poetic and ironic in a way only real life can be. It’s a gift like the moment on Torcello earlier that month when a pheasant rooster darted from the hedge, trailing his elegant tail feathers, blue-green head flicking left to right. Pheasants (fagiani) were all over the island that day, that quiet near-deserted place with its olive grove and out-of-season restaurant and stern mosaic face of Mary shimmering in gold. Each bit of land retains its own life, layered by humans and creatures and time, if we will listen, and if we will look.

I can’t stop thinking about something new in Venice this year. Rearing up out of the Grand Canal in Venice are two giant hands, propped against the surface of the Ca’Segredo: an artwork by Lorenzo Quinn entitled Support. Feels necessary for climate change, for whole city, for each person walking across the squares with the sea unseen underfoot.

In Santa Maria Novella, I stand again, visiting the two men at the wall. My two men, I think of them, however silly it feels. An elderly man in a trenchcoat, carrying a cane, approaches. “Let me tell you,” he says, we’re lucky to be here on a sunny day. On a cloudy day, it’s all dark! But in the sun, the frescoes just glow.” His voice is English, obviously lonely, obviously kind. He comes to Florence often. And he has a story to tell. “My dad was in Italy in 1945,” he says, “and he and another man walked right up to the Uffizi and knocked on the door and they let them in. Only two people in the whole Uffizi.” We both fall silent, imagining it. And it stays with me ever after: the image of two hesitant servicemen in the chaos of war, seeking the peace of art, inside and outside of time. Two men leaning on a wall, rapt by what they’re looking at, invisible to anyone else. Painted by the living hand of the boy who’d grow to be the greatest artist ever, by the teacher who’d be proud to have nurtured him, by some other member of that crew with their creaking wooden scaffolding and their daily giornate and their jugs of lunchtime wine and their unknowable thoughts, by mortal flesh that has long turned to dust and left this mystery behind.

This is the texture of human life that art preserves, that art makes available to us. If only we will listen. If only we will look.

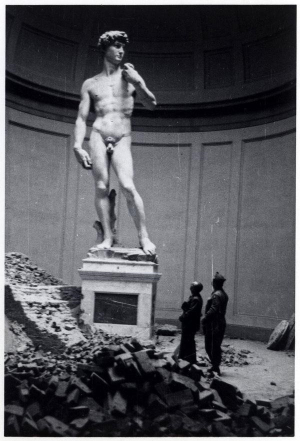

“Michelangelo’s “David” in Florence in the summer of 1945, shortly after the brick sheathing that had protected the marble sculpture was removed.” https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/nyregion/in-new-haven-an-exhibition-on-a-yale-professor-who-helped-rescue-art-during-world-war-ii.html