This season of hesitant and lovely changes began with a scrim of ash that colors the skin underneath, that asks us to look and wait in the times of boredom and worry and anomie, because something more is coming. It always moves me at Lent, the sober lines of people moving from the altar back to their seats, all bearing the mark on their foreheads that never quite goes away. We are wanderers and searchers in a wandering world. Which is why a novel that begins “Call me Ishmael” and ranges thousands of miles over oceans deeper than anyone on that doomed ship could fathom just may be the perfect springtime read.

It’s been an unusually warm spring break for northeast Iowa this week, into the mid-70s in many afternoons: all the daffodils and most of the lilies are up, and the spinach and Merveille de Quatre Saisons lettuce that wintered over in my garden is now rebounding more and more literally every day. Green chives show at the brown roots of last year’s clump. “I saw a single purple crocus in our brown and scratchy-looking yard yesterday and squealed,” writes a friend. “Spring is not just coming, it is here, and all the sunshine with it.” I’ve been clotheslining, sinking my nose deep into the dry flannel sheets before I fold them away. Yet I can’t quite trust this weather. I hesitate to clear all last year’s dried stalks and leaves away, because as Prince — formerly of this region — said, sometimes it snows in April. These new shoots may need last year’s waste to protect them. My friends and I debate, half-jokingly: should we feel guilty about enjoying this weather as the sign of global warming it so obviously is?

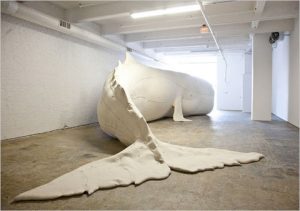

But there’s nothing like sitting in the sun with your feet in new spring grass and reading Moby-Dick for the first time. I’d never gotten around to it before; now I’m a convert. Melville’s contemporary Walt Whitman once spoke of reading as a “gymnast’s struggle” but what I found was that Moby-Dick unrolled around me like a deep and complicated and lingering dream, one that colored my waking vision too. I wasn’t struggling. I was enchanted. At the risk of saying too much and spoiling other new Melvilleans’ experience — because this book is a total psychological, emotional, intellectual, and even physical experience you deserve to have all on your own, one you plunge yourself into and let wash over you, just like the ocean off the Pequod’s bow — it’s starred with offhand moments of wonder that stop me cold in wonder too. From his rowboat, suddenly sucked into the calm center of a whirling pod of whales, Ishmael finds himself peering down into the water at a whale calf (still umbilically attached to its mother) that is looking back.

For, suspended in these watery vaults, floated the forms of the nursing mothers of the whales, and those that by their enormous girth seemed shortly to become mothers. The lake, as I have hinted, was to a considerable depth exceedingly transparent; and as human infants while suckling will calmly and fixedly gaze away from the breast, as if leading two different lives at the time; and while yet drawing mortal nourishment, be still spiritually feasting upon some unearthly reminiscence; — even so did the young of these whales seem looking up towards us, but not at us, as if we were but a bit of Gulf-weed in their newborn sight. Floating on their sides, the mothers also seemed quietly eyeing us. One of these little infants, that from certain queer tokens seemed hardly a day old, might have measured some fourteen feet in length and some six feet in girth. He was a little frisky; though as yet his body seemed scarce recovered from that irksome position it had so lately occupied in the maternal reticule; where, tail to head, and all ready for the final spring, the unborn whale lies bent like a Tartar’s bow. The delicate side-fins, and the palms of his flukes, still freshly retained the plaited crumpled appearance of a baby’s ears newly arrived from foreign parts.

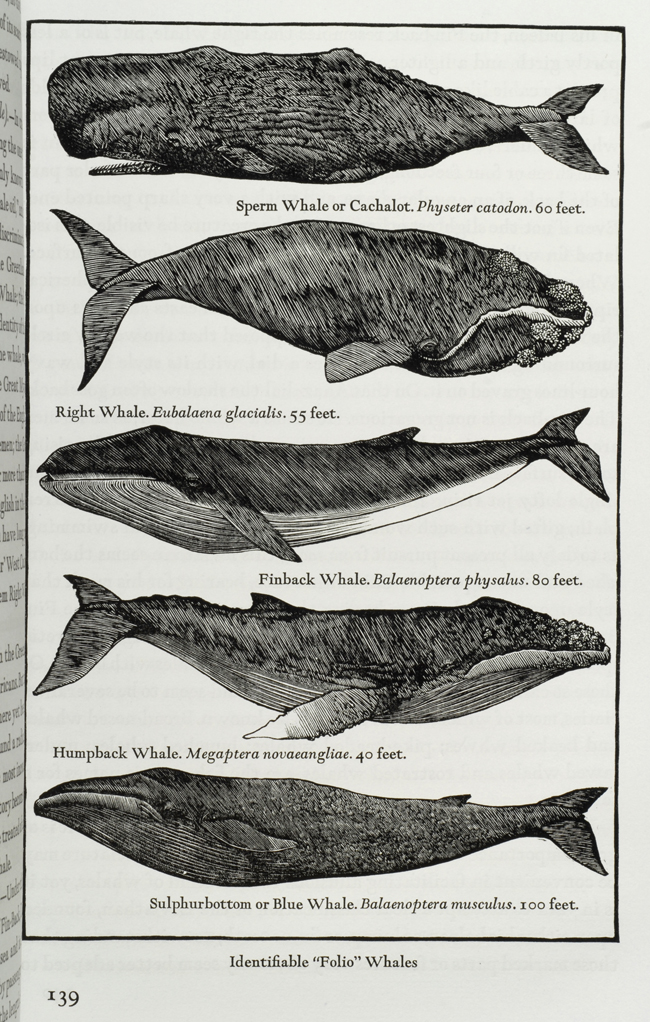

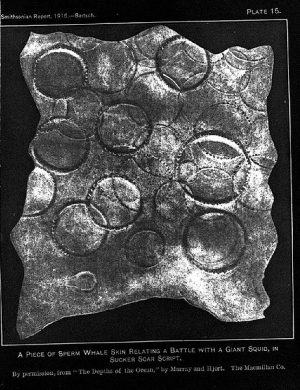

The novel gives the 19th century in its whole breathing, complex life — especially one of its most gruesome, dangerous, and quintessentially eco-exploitative industries, whaling — such a claim on my thinking attention (as Hannah Arendt would say) that I read the whole novel in 2 days, start to finish. It is an experience that submerges you in a gritty and salty and laborious life very close to the edge of what we know of the world, and of the human soul. It can’t be an accident, then, that skin is a dominant image of this novel. Over and over, in direct words and images (from Queequeg’s tattoos to whale blubber sliced on the Pequod’s deck), Melville calls our attention to the vulnerable barrier between us and everything else that, once breached, is never quite the same. From either side.

Over and over, gregarious, disarming Ishmael — especially in moments like the one above, where he’s held helpless in fear or wonder — shows us moments where the skin separating the known from the unknown, the living from the dead, the surface from the deeps, the human from the animal thins, or breaks. Engrossed in spite of myself by the description of bailing out oil from the sperm whale’s head, I’m horrified in the next instant by a near-tragedy as one of the (significantly) “native” sailors on the Pequod comes close to drowning, trapped in that giant head itself, to be saved by another “native.” Melville, like George Orwell writing about English coal mines in The Road to Wigan Pier, keeps our eyes on the real sources of the energy burned so carelessly back on land. Just as Orwell’s miner is “a sort of grimy caryatid upon whose shoulders nearly everything that is not grimy is supported,” Melville’s tattooed whalers, missing arms or legs or fingers or toes (“scarce among veteran blubber-room men”), are literally the source of light for an entire country, and beyond. Chillingly, a boy slave — Dickensianly named “Pip” — loses his mind after he’s snatched out of the boat by a stray harpoon line and left, half by mistake, to tread water in the open ocean for a few hours. In this world, everything depends on looking closely, paying attention, and recognizing reality for what it is.

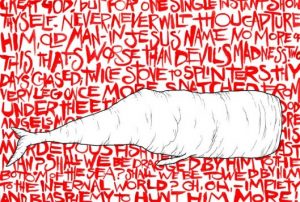

Maybe this is why, as I reluctantly put the book down and moved about my other tasks, one particular image took shape in my mind and stayed with me:

True, from the unmarred dead body of the whale, you may scrape off with your hand an infinitely thin, transparent substance, somewhat resembling the thinnest shreds of isinglass, only it is almost as flexible and soft as satin; that is, previous to being dried, when it not only contracts and thickens, but becomes rather hard and brittle. I have several such dried bits, which I use for marks in my whalebooks. It is transparent, as I said before; and being laid upon the printed page, I have sometimes pleased myself with fancying it exerted a magnifying influence. At any rate, it is pleasant to read about whales through their own spectacles, as you might say.

Through my newly spring-cleaned windows, the world itself appears through a brighter skin, clear and rippled in old-house glass. But over and over I imagined Ishmael’s whale-book with that dried semi-transparent sheet of skin laid over the letters, the ghost presence of that giant beast hanging over the page, mocking and forlorn.

Carrying an image like this inside you changes what, and how, you see. My basement vermicomposting bin’s still going strong, but now as the fruit scraps accumulate and the weather warms up, fruit flies bumble out and tangle in my hair whenever I lift the lid. “Chrysanthemum-based spray,” the worm book recommends. But I hesitate at letting something maybe not entirely pure — as all the commercial sprays I’ve looked at seem to be — into the quiet dark where the worms live, seeping down and into their porous skins. So I’ve made a trap, instead.

Skin. Looking closely enough to see the vulnerability of the places where it joins the world. And taking care.

We know about the poisons that come into our own skins as the result of the thousand small decisions that make up what Michael Pollan calls the Big Problem: “The Big Problem,” he writes, “is nothing more or less than the sum total of countless little everyday choices, most of them made by us (consumer spending represents 70 percent of our economy), and most of the rest of them made in the name of our needs and desires and preferences.” Poisons cross our fragile skins into our breast milk. Into cell and tissue and blood. We’re creatures of sturdiness and delicacy just like the sperm whales; tough fat and muscle crowned with a sheen of cells thin enough to see through.

What we know and that Melville and those old Nantucketers (probably) did not — although Moby-Dick often made me wonder – is that whales do communicate, and they very possibly remember. They plot and they plan. When a giant sperm whale famously rammed the Essex, as Nathaniel Philbrick’s book recounts, it may have been because he heard the taps of the first mate’s hammer echoing down through the water and mistook the giant ship for another taunting male whale. I incline to a possibility Melville only partially entertains but that science supports: whales, like elephants and tigers and some other megafauna, can remember, and plan, and grieve.

So it befits our status as the beast with the world’s most developed brain to keep ourselves fully mindful of, and responsible to, a world in which the costs of our lives are real, and the radiance around us is always waiting to be seen. Kept in our hearts it can change us for good, as Ishmael is changed by his moment in the center of the pod of whales:

And thus, though surrounded by circle upon circle of consternations and affrights, did these inscrutable creatures at the centre freely and fearlessly indulge in all peaceful concernments; yea, serenely revelled in dalliance and delight. But even so, amid the tornadoed Atlantic of my being, do I myself still for ever centrally dispute in mute calm; and while ponderous planets of unwaning woe revolve around me, deep down and deep inland there I still bathe me in eternal mildness of joy.

Oooh–how great that you are reading Moby-Dick. Such sublimity!

My favorite of the cetology sections is Ch. 75, where Ishmael meditates on the position of the whale’s eyes on either side of its head, and its resultant ability to see two entirely different views at the same time. He wonders if that means the whale’s brain is able to apprehend two different truths at once. I love that section because I think Melville points to the secret of most of the failures of the heart: that we cannot exist wholly in the truths of both justice and mercy.

Yes, indeed! Well-said. Thank you so much for reading!

(and I have just now realized that was you, Tara – sorry! didn’t recognize the user id at first… 🙂

Oops–yeah, I don’t know how that happened. Old log-in info stored somewhere, I guess. 🙂

What a wonderful post! I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed reading it… It’s well over twenty years since I last experienced Moby-Dick in full… (‘experienced’ rather than ‘read’ is definitely the right word…) but your wonderful description of how the novel ‘unrolled around’ you ‘like a deep and complicated and lingering dream, one that colored my waking vision too’ brought rolling back to me exactly what that experience felt like. It’s one of those books you truly live whilst reading it, carrying it around with you at all times in between – seeing the world through its filter, through that skin (I enjoyed so much all the connections you make in your references, pictures, quotes etc).

All these years later, the novel’s tipping edges, its reaching beyond boundaries – that stretching the skin of the world, to find how thin and interconnected those boundaries are, and peering in at those unfathomables which are both so elusive, and yet so immediate – all still powerfully live in my memory. Your phrase ‘starred with moments of offhand wonder…’ is an inspired choice of words – so apt! It captures exactly what Melville achieves. I remember a tutorial with my English professor back in my university days, sitting on the very edge of my seat as we discussed that scene when Ishmael finds himself surrounded by the pod of whales – the whole room was alight with all our student responses… Happy days!

You’re so right about mindfulness… I remember a BBC documentary on TV here in Britain, called Ocean Giants, Deep Thinkers. I watched, spellbound, its truly magical footage of the grey whales in Baja California who actively seek out human company. The programme reflected on how not so long ago the grey whales in the area had a reputation for being ferocious, fighting back against the hunters that relentlessly pursued them in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Now, the researchers there studying the whales, are awed by the forgiveness and trust these gentle giants demonstrate. Truly humbling…

Apologies for the long, rambling comment. Your post – indeed your whole blog – is so inspiring!

Thank you for that – and thank you so much too for linking to my blog.

Best wishes,

Melanie

Wow, thank you so much! I really appreciate your reading this essay and taking the time to write such a lovely comment. And thank you for your essays on your blog as well! Wonderful work!!

Thank you – that’s so kind of you to say so! Looking forward to what further unfolds on your blog – it’s great to discover a place of like-minded concerns, and such a well of experience of writers’ work, many of which are new to me.