The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marghanita Laski (1953), published by Persephone Books (1999)

“We think back through our mothers,” Virginia Woolf wrote, “if we are women.” Marghanita Laski’s terrifying novel The Victorian Chaise-Longue (1953) spins this proposition sideways. What if becoming a mother makes a woman a time-traveler against her will? What if mothering allows memory and shared experience and less kindly forces to travel backward and forward in time, with your mortal body as the swinging door? Indeed, childbirth is a mysterious thing: it’s longed-for new life, love, delight; it’s touching the border of death; it’s a portal to emotions that have no names. And for mothers and non-mothers alike, fiction is a way to live in these states without solving them.

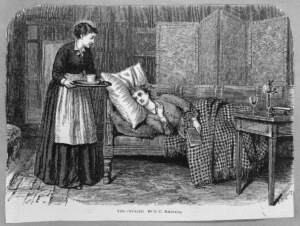

The Victorian Chaise-Longue, Laski’s sixth novel, has been reprinted by London’s excellent Persephone Books, champions of neglected titles by twentieth-century women (and a few men.) Stylish and deft, it’s just ninety-nine pages long. Young wife Melanie falls asleep on a Victorian chaise-longue she and her husband picked out in a junk shop and wakes up in 1864, unable to rise from the couch or to make anyone understand who she really is. As mysterious figures come and go, irritated by the apparently willful misbehavior of the invalid they know as “Milly,” Melanie is reduced to clawing through the layers of her strange clothes to see whether she can still recognize her own body. Like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wall-paper” (1892), Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979), and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1986), this book detonates, in the mind and the bloodstream, a familiar dystopian dread: to be housed in a woman’s body is to be peculiarly susceptible to being overtaken, subsumed, enslaved.

But enslaved by what? As Laski writes it, childbirth is and is not the whole story. “Will you give me your word of honor,” demands Melanie in the novel’s first line, “that I am not going to die?” Her new baby, a healthy boy, is crying in the other room. But the doctor is more concerned about a spot on Melanie’s lung – tuberculosis, that classic nineteenth-century disease – and the feverish frailty it casts over the body, so delicate and feminine and so, accordingly, misread: “She smiled back,” Laski writes, “meaning to say only that she loved and trusted him, and the doctor wondered again how it was that Melanie’s smile seemed always to invite delights he was sure she had never known.” This shift between two kinds of limited-third-person narration is one of several formal constraints Laski employs and explodes to keep the boundaries of reality wavering before our eyes. Technically, the book takes place on a single day – but what day is it, exactly? Our heroine never leaves the couch – but since that couch exists in both 1953 and 1864, it’s not like she stays in the same place. Or does she? The doctor is only the curmudgeonly but friendly advisor, wanting what’s best for her. Or is he? That pink-and-white delicacy, so attractive to him and to her husband – it’s an empowering force, entirely under Melanie’s control. Or is it?

By now, any reader who’s been an adult woman in the world might be nodding along through her horror, recognizing in this novel’s atmosphere and form the particular way that gaslighting shadows flicker off the surfaces around you and the inside of your own head, in personal and professional life. S/he didn’t really mean that the way it sounded/seemed/looked. Surely I must have done – Am I just being too –? As a London literary figure – author or editor of more than twenty books, panelist on BBC quiz shows – and mother of two, Laski might have known at least some of these feelings. While writing The Victorian Chaise-Longue, she deliberately left the city for a remote country house: “in order to frighten the reader,” says P.D. James in the novel’s modern preface, she “needed to frighten herself.”

Frightening this book certainly is, yet in true Gothic fashion, the fear comes from inside the domestic world we think we know. That Victorian chaise-longue, on first sight so innocent – “stacked upside down on top of a pile of furniture, its clumsy legs threshing the air like an unclipped sheep that had tumbled on to its back” – becomes a portal to a languor half-chosen that soon becomes death. Melanie’s vague fantasies of romantic helplessness – “the frail young mother in the floating clouds of negligee, the tender faces of solicitous admiring friends” – become something much worse, troubled by dim memories of lovemaking on that same chaise-longue. The deepest cruelty comes not from a man but from a woman, in a way that anticipates Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan frenemyships and hearkens to our darkest images of the Victorians: “Milly,” unlike Melanie, isn’t married to her baby’s father. “Tell me his name,” growls her controlling sister, “and you shall see your baby.”

The novel never explains the haunting, or kidnapping, of a self into another life; it just asks us to experience, and imagine, it. Melanie is both herself and Milly, a body both living and dead, aware of and unable to resist what’s happening, bound and unlimited by time. The prose expands and contracts in loops of panic and hope. “Wireless, she screamed in her mind, television, penicillin, gramophone-records and vacuuum-cleaners, but none of these words could be framed by her lips. I can think them, why can’t I say them? she begged; can I introduce nothing into this real past? – and if I cannot, then even these thoughts I am thinking, has Milly thought them before? But things can’t happen twice, she told herself wearily, closing her eyes, the momentary relaxation over, the racking torture established again, I must always have been Milly and Milly me. It is now that is present reality and the future is still to come. But if I have to wait for the future, if it is only in time to come that I shall be Melanie again, then that time must come again too when Sister Smith leaves me to sleep on the chaise-longue, and I wake up in the past. I shall never escape – and the eternal prison she imagined consumed her mind, and she fainted or dozed off into a nightmare of chase and pursuit and loss.”

You finish The Victorian Chaise-Longue round-eyed with a horror that settles inside you in waves, like the sand at the bottom of a river once the swimmer stops kicking. And then you turn back to the first page and read it all over again. In her lifetime, Laski was one of the top contributors to the Oxford English Dictionary, building up the history of each word as a tool with a long life behind and ahead of it. The Victorian Chaise-Longue, too, testifies to the power of writing to get inside any experience and look around, no matter how distant, or how intimate, it may seem.