To many of us, the year 2020 felt like the first draft of apocalypse. The COVID-19 pandemic claimed nearly two million dead worldwide. Lockdown life drove minds and economies around the bend. George Floyd was murdered by a policeman on a Minneapolis sidewalk. Brexit disaster flapped down on rusty wings to roost on the once-United Kingdom. Wildfires burned up the West Coast. And defeated incumbent Donald Trump ranted that the November US Presidential election had been “stolen” from him. Like everyone, I hoped 2021 would mark some kind of break. Alas, that didn’t happen.

First came illness: around New Year’s Day, I realized what I thought was just a winter cold had been deepening for an awfully long time. Then came chaos: on January 6, after Trump rallied them up, a mob of mostly white insurrectionists in MAGA hats and camo and hoodies stormed the Capitol building. They broke windows and toppled barriers and sent elected officials scrambling for gas masks and huddling onto the chamber floor. They invaded offices and stole computers and the House Speaker’s gavel. They carried guns and zip ties and nooses for the capture of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Mike Pence, believing, erroneously, that Pence could stop the certification of President-Elect Joe Biden’s entirely legal election victory. They carried Confederate flags and STOP THE STEAL banners and smartphones to film themselves lounging in the House Speaker’s chair and placing a red MAGA hat on a bust of George Washington. Then came diagnosis: on January 8, I learned that despite months of caution, I had tested positive for COVID-19. And, always, there was teaching: on January 7, I met on Zoom with my students, propping my laptop on my rickety dining table, to teach a course I’d named “Romanticism for a World Upside Down.” Today, we’d talk about John Keats (1795-1821).

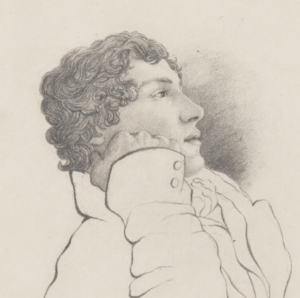

When I introduce students to this stubbornly enigmatic, irresistible man – one of the most remarkable, funny, brilliant, ironic, sad, sexy, ambitious artists who ever lived – I usually start in the same place. You’re twenty-three, I begin, and you know three things. One, you’re a talented poet – talented enough to take the risk of leaving your brand-new medical careeer. And it is a risk: you have three younger siblings, and medicine is the safe career that’s supposed to set you all up for life. Yet you’re following your dream of being a writer, even though your grumpy guardian calls you a fool. Two, you’re in love with the girl next door, Fanny, who lives on the other side of the duplex you’re sharing with your best friend Charles. You’re only five feet tall and so you’ve been self-conscious about girls before, but this girl – she’s something else. Three, you’re terminally ill, with the same disease that killed your mother and your younger brother Tom, who literally died in your arms. Tuberculosis, known in the nineteenth century as consumption. It’s a bad disease. Like COVID-19, it rots your lungs from inside. Like COVID-19, there’s really not a treatment, or a cure. So. How do you live in this reality?

Students’ faces grow somber. The youngest of them is twenty, the oldest is twenty-two. Of course, they’ve been living with irreconcilable realities themselves. Class now happens on a computer screen. Career is an even more precarious proposition than it was after the 2008 recession. COVID has sent them back to their childhood bedrooms and the familial roilings (grandparents’ deaths, parents’ job loss, homophobic uncles) that school gives them room to dodge. And climate is thrust on them by their elders like David Cameron handing off the Brexit referendum to Theresa May: good luck with this thing I made – I’m outta here! Despite the ahistorical social-media fog in which they’ve been known to drift, they’re also, in David Bowie’s words, quite aware of what they’re going through. And, like Keats, they have reason to wonder exactly how knowledge might help them. Let’s get real. If COVID or consumption makes each breath a struggle, it might help you to know your symptoms, to chart their progress, to put yourself in a medical story over which knowledge might theoretically offer you control. Then again, it might not help. Especially if you know there is no cure for your disease. Especially if you’re not sure how long chest-rattles and fatigue and depression will haunt your body and darken your mind. Especially if you have to face reality although that reality seems irreconcilably divided between joy and pain.

In his last days in a rented room in Rome, Keats, aged twenty-five, woke weeping with frustration to find himself still alive, struggling to breathe, living what he railed at as a posthumous existence, unable simply to die, to cease upon the midnight with no pain. That line comes from “Ode to a Nightingale” (1819), one of the most beautiful poems ever written in English, composed by Keats on scraps of paper as he sat in his Hampstead duplex‘s garden in a kitchen chair, listening to a bird’s song unspooling itself in the twilight. We know from his roommate Charles Brown that this poem was nearly lost due to its creator’s own diffident preoccupation. “Coming in from the garden,” Brown reports, “he had some pages in his hand, which he thrust behind the books in the case.” Brown rescued them and persuaded Keats to finish them. Those scraps became this poem. Keats was then twenty-three, bearing an unbearable self-diagnosis of consumption and gift. And – although he would never be able to marry Fanny – of love.

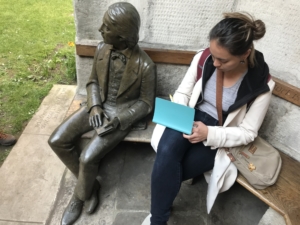

I love Keats. And students love him too. Perhaps I owe him my whole career: my true vocation as a teacher began when, as a graduate student in a classroom on the third floor of Greenlaw Hall at UNC-Chapel Hill in 2002, I described Keats’ death to a roomful of sophomores and spotted a red-haired girl named Jennifer, two-thirds back on the right, surreptitiously wiping her eyes. Jennifer came up to me afterwards – “I’m sorry, Ms. Weldon, his story is just so sad…” Don’t apologize, I blurted, it shows you care. We awkwardly, impulsively hugged, and Jennifer left smiling through her tears, on her way to the library to read more Keats. Students are still moved by Keats: at his gravesite in Rome, in his bedroom in Hampstead, in my classroom in snowy Iowa. But in the COVID-19 era, I can’t hug them: like Keats quarantined on his invalid couch in the parlor and Fanny standing in the garden to wave hello, we’re on opposite sides of invisible glass, relying on – hoping for – what Keats would have called sympathy to cross that space. Amazingly often, it does.

Orphan, doctor, poet, sturdy, self-conscious young dude bursting with life on and off the page: Keats feels easy to know, and easy to love. His small body seems to bear more of everything – more humor, more irony, more intensity, more beauty, more zest for existence – than other people’s, including our own. We seek intensity, rapture, taken-up-ness, meaning-ful-ness. We find them in the story of this doomed, loveable, heartbreaking man. But there is more to Keats’ story than we think. And going deeper into his reality and his art can help us navigate our own broken, upside-down, still-beautiful world. Especially since it’s also a world in which – just like John Keats, self-diagnosed at 23, dead at 25 – my students face a future obstacled or cut short through absolutely no fault of their own. Yet we all must find a way forward, regardless, discovering what we still experience as our vocation to make something meaningful, purposeful, and beautiful in the one life on earth any of us will ever have.

From the draft of my chapter-in-progress on Keats from my book-in-progress, An Awful Rainbow: Reading the Romantics in a World on Fire. Glad to report that I am completely recovered from COVID.