Delivered as a guest sermon at First United Methodist Church, June 11, 2017, for Peace and Justice Sunday.

Psalm 8: “When I look at thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars which thou has established; what is man that thou art mindful of him, and the son of man that thou dost care for him? Yet thou has made him little less than God, and dost crown him with glory and honor. Thou has given him dominion over the works of thy hands; thou hast put all things under his feet, all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field, the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of the sea. O Lord, O Lord, how majestic is thy name in all the earth!”

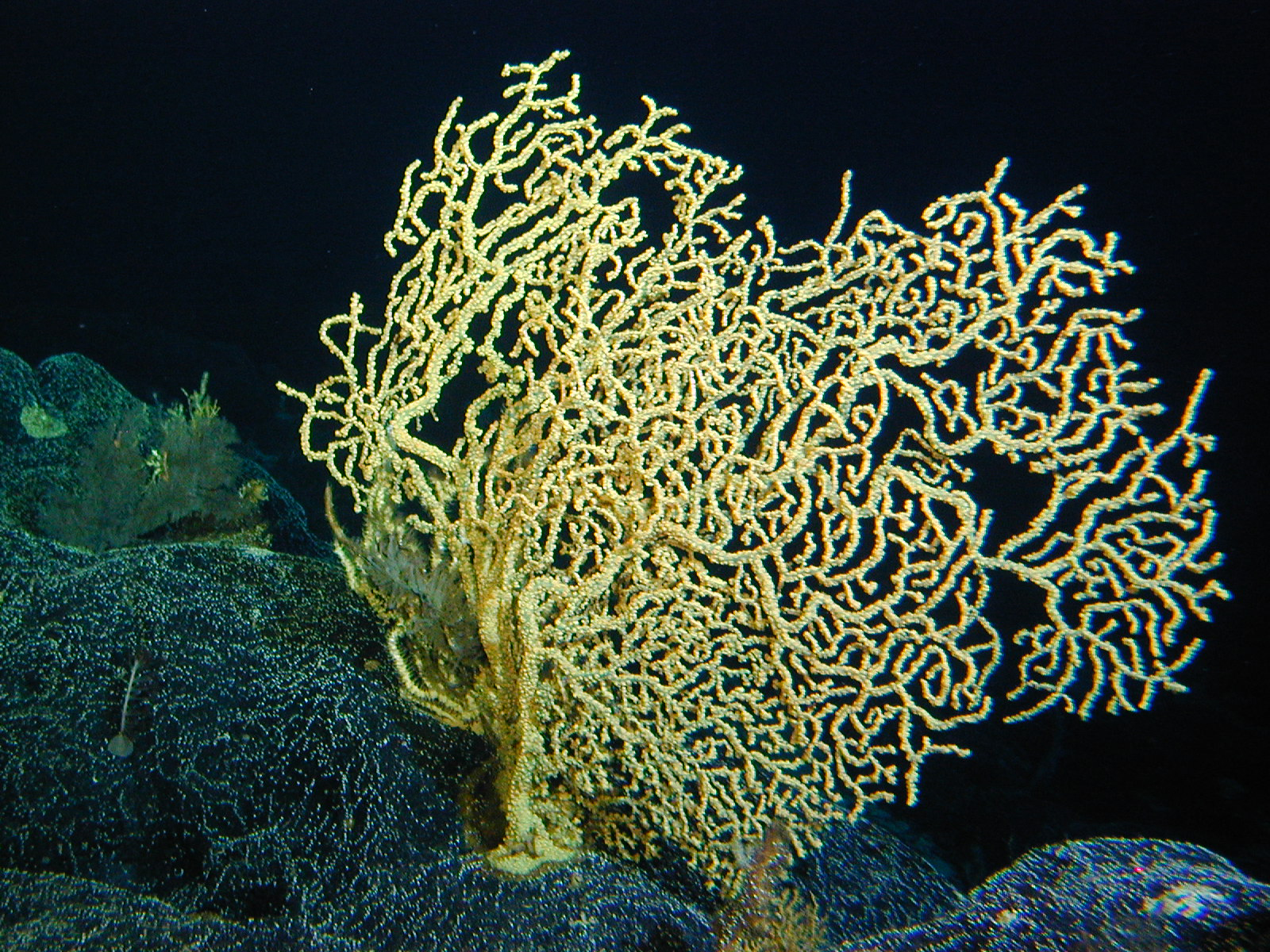

The moon is getting farther from the earth. One sign of this is corals, those miraculous undersea formations now bleaching and dying as climate change warms and sours oceans. The tiny creatures that live in corals move in and out over millions of years, making tiny paths, striations whose distance charts the motion from the earth to the moon over time. One thing it shows: a year is now shorter by forty days. Some of these corals are 450 million years old. Stop and take all this in, or listen to the episode of Radiolab that describes it, and you’ll feel a familiar combination of emotions: wonder at the intricate handiwork of our world, grief at how little humans have done to deserve and how much to destroy such bounty.

Corals and the moon; homeless men sleeping on church pews as they chase the fracking boom in Willesden, ND; brothers and sisters (because we are all brothers and sisters and fellow humans, aren’t we?) experiencing economic and environmental and physical violence because the color of their skin sets off something inside a different-colored person’s head. At Luther College, where I teach, we’re fond of saying We are God’s hands and feet. Yet so much suffering among the humans and nonhumans all around us can freeze us in place. So here on “Peace and Justice Sunday,” let’s think together about the ways we make redemption real. What is it we are called upon to do?

The first layer of answer is simple. What does the Lord require of you but to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God. But like so many spiritual truths, there is such complexity and even difficulty hidden in this statement. I’m an English professor, so I start with that one verb, do. Recently I ran across a book on medieval herbs, which quotes a 1390 recipe from English King Richard III’s cooks for something called “Douce Ame:” “Take good cow milk and do it in a pot. Take parsley, sage, hyssop, savoury, and other good herbs and hew them and do them in the milk and seethe them. Take capons half roasted and smite them in pieces and do thereto pyn [which a quick OED run leads me to think may be pine nuts] and honey clarified. Salt it and color it with saffron and serve it forth.” I’d never seen this use of the verb before but warmed to it instantly, so to speak. This is after all a verb of action, of the millions of tiny stirrings within a thing produced by heat or conviction or other irresistible forces. Cooking, heating, transferring energy, making the thing that feeds, altering the state of something so our bodies can receive it and transform it into more energy are all governed by that verb: do.

Do unto the least of these, Christ commands, and you do unto me.

In my favorite story by the great North Carolina author Allan Gurganus, a widow on an ordinary Tuesday catches an angel as he falls to earth, nurses him, receives from him a blessing, and then cheers him on his way again. “Go,” she shouts. “Go. Yeah. Do.”

My Alabama people – all of us – know in our bones the persistence of Jacob: I will not let you go until you bless me. You’ve got to pray hard, work and walk, grab ahold and not let go, keep asking. Do and do again. Link your arms and keep singing as you cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge where it crests, just over the Alabama River, and start down the opposite bank, into the line of policemen waiting, clubs in hand. Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around. Ain’t it wonderful what God can do.

Empathy is something humans can do, and it works. How much of history would be different if we let the presence of one another’s bodies, the reality of their pain, shame us into awareness, knowledge. What happens when human limbs are hung from the limbs of trees. What happens when power gathers up and rends another’s flesh, when the casualness of assumption or greed eats humans like the monster in the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son, stuffing a living being into its mindless maw. Moloch. The beast. That beast lives in our hearts. That beast is real.

It is easy for me to talk about race and justice and trying to do better, to learn about it. Because I can read the books and talk to people and try to learn – which I am – but I can choose not to know it, too, can choose to put down the book and go about my day. I have that privilege. Other people don’t.

The person who said those rueful words to me was a white man in his seventies, a writer and professor originally from the South, like me. I know their truth is also true for me, and that that truth is not fair, and is not right. If you’re white, you go around in a body that will let you forget things others’ bodies and hearts are never allowed to forget. This is where some of us might start to shift in our seats and murmur doubtfully about political correctness, which, like any human tool, can indeed be used to flatten ourselves and each other. But in the words of at least two Republican senators I heard and read during the 2016 election cycle: “There is political correctness, sure, but there is also common decency.” There is the empathy that shares a common body, the language of the senses in which we speak to one another across place and time about how we do things in this world. I look at black women I know and realize I can see and feel visceral sympathy but ultimately can only touch an edge and shrink back, like snail-horns, to safety inside the shell of a white body. They live in bodies for which the news is telling us, again, there is precious little safety from the world.

Perhaps language can provide not only ways to understand but tools to help in our doing justice and loving mercy and – this seems so important – our walking humbly, with God and one another. The biologist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer, a member of the Native American Pottawatomi Nation, says that if we had different pronouns than “it” for nonhuman plants and creatures, we might be more inclined to recognize them as living beings, worthy of respect. She proposes the phoneme ki, which has been used in native languages to mean place (think Milwaukee). In the Pottawatomi language, adding an n to words makes them plural: therefore, adding an N to KI gives you KIN. Think of it: watching a V of geese moving across the sky, their wings making a subtle shiver of sound in the air, you could say, “Kin are moving south.” Studying those miraculous corals, you could say “Look at the paths kin have made, over 450 million years.” This might then enchant the world in a grammar of beholding, helping us see fellow beings as the wonders they are. Similarly, how would our life together in our world look different if our mental label for another’s face on catching sight of them was sister, brother, you.

Yesterday I read that Arctic ice is approaching its lowest level in 30 years. Studies suggest that every American releases, through our energy use, enough carbon dioxide to melt 645 square feet of arctic ice in a year. That’s 645 feet per person per year. Melted. Not coming back. For which I am responsible. I have erased something rare and built-up over time, carrying within it traces of past eons and times as richly as coral carries the marks of small kin creatures tracking the moon. For my refrigerator, for my air conditioning, for my car and, yes, the plane on which I flew to the conference at which I learned about coral creatures and Arctic ice and how to care for them. This is our moral work and moral duty, to collapse distance between us and them, me and you, it and kin. Think of Christ laying hands on lepers and bleeding women, laying hands on bleeding world. Yet ours is also the world praised by the psalmist, who despite the use of the word disastrously translated into English as dominion soon dissolves into wonder. “When I look at thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars which thou has established; what is man that thou art mindful of him, and the son of man that thou dost care for him? Yet thou has made him little less than God, and dost crown him with glory and honor.” A power which, the conclusion is inescapable – we have not used wisely or well. Doing better is a matter of urgency. And one that leaves us standing in the necessity of grace.

Thanks to Camille Dungy, Robin Wall Kimmerer, John Elder, and the Bread Loaf/Orion Environmental Writers Conference for information and inspiration.

Oh my goodness, you wrote a sermon and I am so proud! Thanks for taking on a topic which is so close to your heart and that of many others. It’s amazing to listen to the climate change deniers. We are living in the days of false prophets who are leading good people along paths that lead to dead ends. More later, I miss your face. I miss your wisdom and sparkle.

Aw, thanks, friend. I miss you too and hope you are doing well. And if I’m preaching sermons, it’s because I had a good role model. 🙂