“May you live in interesting times,” says an apocryphal Chinese curse. And for a Romanticist writing about Byron, boxing, and the celebrity culture of Regency England, the news that AI can now fake even more human creations is “interesting” indeed.

Now AI has made a “song” by Drake and The Weeknd that neither artist authorized or performed. Listening to the New York Times’ podcast on this – including a deepfaked conversation between Biden and Trump, pretending to commiserate about the difficulties of the presidency – I see this as a new extension of the devouring heart that’s always beating in the chest of celebrity culture: we will commodify and pare you down to your meme-able, humm-able essence, regardless of how your actual human self feels about that. Why care? Even if you think this is only about a couple songs, even if you admit that trying to control this stuff is like trying to hold water in a sieve, remember the Jan 6 insurrection and its Pizzagate prefigurations: in a society where people triggered by fake news go out to “solve that problem” with guns, what will be the legal and moral recourse for those whose loved ones have, in a manner of speaking, been killed by AI? How to track down the source of an AI “hallucination” that falsifies history on its own – and will be believed? In the words of one NYT commenter from Chicago, on the news that AI videos are now a thing: “No one asked for this, no one wants it, more humans will lose jobs, disinformation will increase 1000 times, and there are no regulations on it. Did I miss anything?”

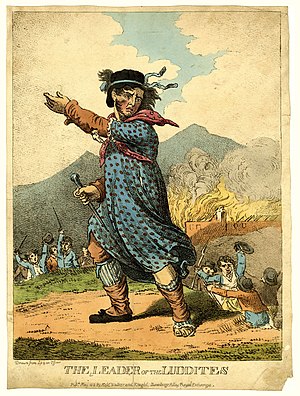

Unsurprisingly, I don’t think this deepfakery is good for artists, no matter how many gamely state they look forward to creating “with” their possible replacements. (God forbid you look like a Luddite! [See below.]) Nick Cave, typically, has a great response. So does the Authors Guild, now writing anti-AI measures into new contracts. Jaron Lanier has been teaching, for years, how an internet built on the siphoning-off of our uncompensated data impoverishes us all. What futures are young artists supposed to look forward to if they’re just shuffling forward in a nervous crouch, half-building for and half-dreading the big break that will make them meme-able, steal-able “brands?” To be sure, traditional music and publishing models haven’t been exactly directing great profits to “creators” anyway.* But the AI mashup is the perfect “art form” for the distractable, attention-deficited, influencer-obsessed twentieth century, a kind of GenZ electronic scrapbooking. Borrow someone else’s original voice or image, bask in the cachet of the “brand” they have created, tweak some things in your laptop, and post for likes! Who needs the original? Who, after a while, will remember it at all?

So how does all this connect to boxing? Having now completed a chapter on Lord Byron (who, among his other athletic feats, trained as a boxer with the Regency’s star trainer, “Gentleman” John Jackson) for my next nonfiction book, I’m discovering that boxing (then and now) provides a way to get intimately involved with the uneasy dance that both these pursuits provide between authenticity, celebrity, commodification, and art. This research is utterly fascinating – and often startlingly contemporary, running you right into objects and events and, for our purposes here, kinds of fandom and replication that we still know.

Take a marvelous panoramic drawing by Robert Cruikshank, “Going to a fight: the sporting world in all its variety of style and costume along the road from Hyde Park Corner to Moulsey Hurst,” published in London by the firm of Sherwood, Neely & Jones in 1819. Now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, it’s a single strip of paper, fourteen feet long and exactly the width of a sideways-turned iPhone. To view it, you hold its round wooden case in your left hand and unroll it slowly with your right, “reading” the long procession as it literally moves across your field of vision. A man leads his bull for dog-baiting (a sideshow to the human fight.) There are scuffles on the road and horses for sale and even a guy on a bike. Finally, we reach the fight itself: Jack Randall (“the Nonpareil,” whom John Keats saw just after his brother Tom’s funeral) vs. Richard West (“West Country Dick”) on April 3, 1817. Pierce Egan, king of Regency sportswriting, is hunkered by the ring, taking notes. (Click the link above to read all about it.) An early fan artifact, it’s also proto-cinematic – even a forerunner of a graphic novel – combining art, fandom, and spectacle in a way a hundred Muhammed Ali posters would later repeat.

Then there’s “Gentleman” John Jackson (1769-1845), who kept a celebrity boxing gym in his rooms at 13 Bond Street, in the heart of fashionable London. A former boxing champion of England, Jackson was a well-liked, mediagenic guy, although he was never quite able to dodge the accusation that he had cheated in his bout against Daniel Mendoza, “the Fighting Jew,” by grabbing his long hair (might these have been the traditional Jewish payot, or side curls?) Mostly, Jackson was known for his looks. “Now there is a man,” the Prince of Wales supposedly remarked upon seeing Jackson (who later returned the favor by organizing a group of notable boxers to walk in the parade for “Prinny’s” coronation as George IV.) Thanks to Sir Thomas Lawrence, who painted Jackson as Satan in “Satan Summoning His Legions” (1791) and a young listener in “Homer Reciting His Poems” (1790), we can see just how, like another scrapper-turned-model two hundred years later, Jackson made his good looks work for him. On his worn monument in Brompton Cemetery, you can still just see his handsome profile and the letters -AESTUS, which must refer to Hephaestus, God of the Forge (what a great epitaph for a boxing trainer!) Look at the images below: can you see why I like to call Jackson the “Marky Mark” Wahlberg of Regency England?  Left to right: Sir Thomas Lawrence, Homer Reciting His Poems (1790), with Jackson as the boy on the ground, Tate Britain; Sir Thomas Lawrence, Satan Summoning His Legions (1796-1797), with Jackson as Satan; and a GenX teenage crush, “Marky Mark” Wahlberg (1992)

Left to right: Sir Thomas Lawrence, Homer Reciting His Poems (1790), with Jackson as the boy on the ground, Tate Britain; Sir Thomas Lawrence, Satan Summoning His Legions (1796-1797), with Jackson as Satan; and a GenX teenage crush, “Marky Mark” Wahlberg (1992)

Jackson is also pictured on the famous “Byron screen,” a standing screen now on display at Newstead Abbey (Byron’s ancestral home) and covered with decoupaged images of boxers. (Once thought to have been made by Byron himself, it’s more likely to have been made by his fencing trainer Henry Angelo, who shared Jackson’s gym as teaching space.) Jackson is the man in the far right panel in the blue coat, chivalrously holding his hat over another fighter’s crotch.

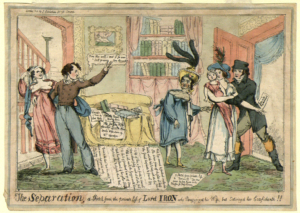

Celebrity was something Byron himself both courted and feared. As Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass would become a few decades later, Byron was perhaps the most-image-ized man of the Regency period, often reduced to his most instantly recognizable, brand-ready essentials – a long white throat, a tumble of dark curls, and an imperiously lifted profile. Canny about his image in the press, shrinking from and courting exposure – always half-in, half-out of any circle you try to draw around him – his brand of celebrity is one we recognize. In countering a rumor that he’d abducted a Venetian countess, he wrote, “I should like to know who has been carried off – except poor dear me – I have been more ravished myself than anybody since the Trojan war.” English tourists in Venice “thronged to his known point of disembarkation at the Lido,” where he came to ride horseback on the beach. It was “amusing in the extreme,” wrote his friend Richard Hoppner, “to witness the excessive coolness with which ladies, as well as gentlemen, would advance within a very few paces of him, eyeing him, some with their glasses, as they would have done a statue in a museum, or the wild beasts at Exeter ‘Change.’” Women spied across Lake Geneva with telescopes at his laundry spread across the bushes to dry and sent him fan letters with locks of their hair (not only from their heads). More than one cast herself theatrically as the addressee of his love poem “To Thyrza.” Nobody knew Thyrza was actually John Edelston, a beloved choirboy from Byron’s Cambridge days. Nevertheless, the lyric’s intensity inspired young Mary Godwin to adopt it and write it dreamily in her own copy of Queen Mab, given her by her new lover Percy Shelley. And dreamy is the word, that eternally sighing, longing teenage word. Remember how it was to write those lyrics in your journal that seem written by a stranger just for you, to have cutout pictures of your favorite actors or boy-band singers on your bedroom closet door? How dreadfully easy it is to see those people as less than human, as only projections of your desires, as only shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave, dancing and flickering just for you.

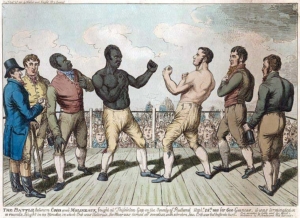

Like professional athletes today, several boxers – like two-time English champion Tom Cribb (1781-1848), who founded a pub bearing his name that still stands on Panton Street in London – invested in their futures beyond the ring, knowing that celebrity could be an inherently unstable force. After Byron dined at Cribb’s house in 1813, he notes: “Tom has been a sailor – a coal-heaver – and some other genteel profession […] and is now only three-and-thirty. A great man! Has a wife and a mistress, and conversations well – bating some sad omissions and misapplications of the aspirate.”

But other working-class boxers learned that becoming His Lordship’s amusing toy was risky. In his great multivolume history Boxiana, Pierce Egan is at pains to describe how one Captain Godfrey, ex-soldier, boxing patron, and amateur, is “no finicking FOP, or empty SWELL, that ran after PUGILISM, because it was thought knowing and stylish.” He might have been thinking of Richard “Hellgate” Barry, 7th Earl of Barrymore, one of the Regency’s most notorious rakes, who married the daughter of a boxer (herself a sometime fighter, she later became a prison matron at Bridewell) and died at 24. Barrymore and his three siblings were mocked with London-landmark nicknames: Richard was “Hellgate,” gambler Augustus was “Newgate” (after the only prison he hadn’t been inside), Henry (who, like Byron, limped) was “Cripplegate,” and their foulmouthed sister Caroline was “Billingsgate” (fishwife – get it?) Caricatured by James Gillray as a skinny, pouting dude in boxing gloves, “Hellgate” liked to start fights, then call in his pet boxer, Bill Hooper, “the Tinman,” to bail him out. Originally from Bristol (like Tom Cribb, Bill Neate, and Jem Belcher), Hooper turned from making “sausepans” toward the high life, then was abandoned when the fun wore off. “The swell tinman, Hooper,” Egan relates, “was one of those ‘playthings’ of the great; and, sheltered under the wings of nobility, he became pampered, insolent, and mischievous.” When Hellgate tired of Hooper, he turned him out to succumb to drink and disease. Eventually Hooper “was found insensible on the step of a door in St Giles” and “on inquiring who he was, he could only very faintly articulate, ‘Hoop – Hoop.’” Luckily Hooper was “recognized as the miserable remnant of that once powerful pugilistic hero” and “humanely taken to the work-house, where he immediately expired.” Could Egan have seen “The Wizard of Oz” more than a century later, I’m sure he’d hearken to the pathos of the technicolor Tinman, slumped and rusted in place, longing for a heart.

Byron gets dismissed as heartless playboy, then and now. But he would have hearkened to the pathetic Tinman too, hollowed out by celebrity. Because he knew how chasing after simulacra, and replacing humans with machines, could hollow out a human life. Making his maiden speech to the House of Lords in 1812, he took the highly unusual step of defending – wait for it – “the Luddites,” the Nottinghamshire weavers who had rebelled against the machines stealing their livelihoods by smashing the machines. His new colleagues wanted to impose the death penalty. His whole speech is inspiring, still. Here’s just a bit, laced with his already-recognizable sarcasm:

“Considerable injury has been done to the proprietors of the improved frames. These machines were to them an advantage, inasmuch as they superseded the necessity of employing a number of workmen, who were left in consequence to starve. By the adoption of one species of frame in particular, one man performed the work of many, and the superfluous labourers were thrown out of employment. Yet it is to be observed, that the work thus executed was inferior in quality, not marketable at home, and merely hurried over with a view to exportation. It was called, in the cant of the trade, by the name of Spider-work. The rejected workmen, in the blindness of their ignorance, instead of rejoicing at these improvements in arts so beneficial to mankind, conceived themselves to be sacrificed to improvements in mechanism. In the foolishness of their hearts, they imagined that the maintenance and well doing of the industrious poor, were objects of greater consequence than the enrichment of a few individuals by any improvement in the implements of trade which threw the workmen out of employment, and rendered the labourer unworthy of his hire. And, it must be confessed, that although the adoption of the enlarged machinery, in that state of our commerce which the country once boasted, might have been beneficial to the master without being detrimental to the servant; yet, in the present situation of our manufactures, rotting in warehouses without a prospect of exportation, with the demand for work and workmen equally diminished, frames of this construction tend materially to aggravate the distresses and discontents of the disappointed sufferers. But the real cause of these distresses, and consequent disturbances, lies deeper. When we are told that these men are leagued together, not only for the destruction of their own comfort, but of their very means of subsistence, can we forget that it is the bitter policy, the destructive warfare, of the last eighteen years, which has destroyed their comfort, your comfort, all men’s comfort;—that policy which, originating with “great statesmen now no more,” has survived the dead to become a curse on the living unto the third and fourth generation! These men never destroyed their looms till they were become useless, worse than useless; till they were become actual impediments to their exertions in obtaining their daily bread.”

Byron would have asked the same question my students and I are asking now: in pursuing simulacra, celebrity, pleasure, ease, where are we letting ourselves be led? When we go for the easy over the challenging, what are we giving up? How are we letting ourselves be hollowed out – and what hallucinations and new “intelligences” stand ready to take our place?

* Yes, I am aware that I am feeding the Internet with my own words right now. But I am also driven by a public-intellectual imperative to create and communicate ideas. Which is, technically, my job. And which I write books, also, to do. Maybe the day will come when I’ll stop even this modest “input” to the AI theft machine via blog. But then that’s just further actual-human silencing / irrelevance, isn’t it? Thanks, twenty-first century!