This year I’ve tried two ways – printmaking and welding – to get under the dirty, stubborn skin of William Blake. Both rely on fire to inscribe your intention and an elemental ground – paper or metal – to preserve and transmit it. Both ask you to dedicate yourself to learning an art that won’t stick with you until you make a practice of sticking with it, submitting your body and mind to be, literally, reshaped. Both ask you, literally, to change the way you see. And if you put aside your fear and awkwardness and give them a try, both will show you something like how it might feel to see the world as Blake saw it. Even more, both will give you what art can give anyone – the continuously inwardly renewed wellspring of curiosity and freshness, the constant defamiliarization and susceptibility to chance and acceptance of randomness, that the Romantics have entrenched in the bloodstream of every artist who follows them. Because both printmaking and welding ask you not only to envision a thing you want to make but employ your whole body and mind in making it, discovering what that thing will be as you respond to the fact that materials may have minds of their own.

As a printmaker, Blake could work in a variety of media, but he’s best known for the medium he invented: relief etching. Taking a square of metal roughly the size of a vintage Penguin paperback, he would write and draw his design backwards in wax on that surface. (You have to write backwards on your plate so the design prints the right way on the paper, since paper and plate are mirror images of each other.) Then he’d wrap a dam of wax around the outside edge of the plate and flood the plate with acid. Gradually, the acid would eat away the unprotected surface of the metal, causing the wax-drawn design to rise up as a three-dimensional pattern. Then Blake could mix his ink and pat it carefully with a leather pad or roller onto that risen design. Laying the inked plate face-up in the press, then placing his paper and blankets over it, Blake – like the captain of a sailing ship, swinging his craft into the wind – could give a mighty heave to the press’s star-shaped wheel and roll his new image through the machine and out the other side into existence.

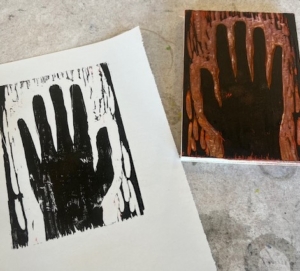

I never got to the level of acid etching, but I did learn the basics of woodblock printing, linocut printing, and etching on Plexiglass. Mentally rearranged with each class, I found myself learning things: You cannot write “normally” on a surface and expect it to print “normally.” The beautiful image in your mind may be something you lack the skill to execute, or something you just can’t do with your medium. (Cutting delicate raised script into wood with standard woodblock-cutting tools takes more skill than I have.) And you return to the body, over and over. Your hands swell, get cut, get chapped, get rougher, get stained, get stronger. You have a permanent rim of ink under your nails and around your cuticles. You learn to recognize the particular rasping sound of the proper thickness of ink under your roller. You learn the texture of rag paper that’s soaked in water long enough to lock in your ink. You learn patience. Frustrated and intimidated, you realize: this is how your students feel, on their first day in your class on subjects you’ve been teaching for 20 years. And you live suspended between chance and responsibility: You’ll never know how your art piece might look until you try it. You have to use what’s there in the studio and your materials and your mind on any given day. But once you make a thing, it’s there in the world with you. You can print from the same block multiple times in different colors, to different degrees of lightness or darkness; Blake printed in outlines and then, with his wife Catherine, colored them in by hand.

And once this art has been born, it might do anything – just like a new-born person. Words and art peel – no, burn – away the bullshit from a world full of it and show you what is true.

“A house with bottle trees” (Simpson Co., MS, 1941) by Eudora Welty

For years I’ve envisioned making a bottle tree for my backyard, just like the one in this famous Eudora Welty photograph. A rural Southerner, I also love their connections to seventeenth-century English “witch balls” and Middle Eastern traditions of djinns and lamps. Plus: I wanted to know if I could realize the naïve vision in my head: take a handful of rebar, fasten it in the middle, and then heat the “branches” until they were hot enough to bend. Wicked.

What I didn’t expect, when I signed up for a welding class at last, was how much this art would also connect me back to Blake – who would have loved the way an arc welder literally lets you write with fire. Like God’s finger on the wall at Belshazzar’s feast, like Blake’s own wax-dipped quill on his copper plate, like the image of the divinely inspired artist: whatever you inscribe or mark with an arc welder is going to stay there. And it’s no accident that in Blake’s mythology, the figure of the artist – Los, who declares “I must create my own system or be enslaved by another man’s. I will not reason or compare; my business is to create” – is a blacksmith.

On a Tuesday night, my teacher Kelly Ludeking fires up for us a welding machine in a box a little larger than a big sewing machine, with a long flexible hose at one end and a fat electrical plug at the other. Through the hose is threaded copper-coated wire that peeks from a handheld nozzle at one end. It works on the same principle as a string trimmer or a glue gun: pull the trigger and electricity cycles through the machine to feed the wire forward to you from its interior spool and super-heat its tip, creating, literally, a pen of fire. With this tool, you are etching the world, unchangeably.

Kelly positions 2 slabs of scrap iron together at a right angle on a metal-topped table; we’ll work along the joint to weld them together. I watch the other 3 students in class – Nancy, Owen, and Lisa – drop their helmet hoods, bend over the table, and circle the welding tip along the joint in overlapping cursive l’s, as Kelly instructs. “Press it in! Keep it moving! But not too fast. Breathe. There’s a Zen of welding.” Through the helmet lens I can see only a greenish-white star that showers orange sparks outward at not-quite-predictable intervals. Lift the helmet and I see red-hot molten steel, cooling to mercury-silver, pooling like insulation foam or wood glue in the joints: except that, as Kelly says, “when you weld on top of welding, it all becomes one thing, not separate layers like old and new glue.” A whole thing, wholly itself, born in an instant, with no do-overs or second guesses. It’s Blakean as hell. It’s intoxicating. And it’s terrifying.

I watch all 3 classmates. And then it’s my turn. In the instant before I take that nozzle in my hand, I’m flooded with a fear so intense I want to bolt right out the open garage-shop door. “I’m scared,” I blurt. “You got this,” Nancy, Owen, and Lisa comfort, gathering round and patting my shoulder. Kelly consoles too. “I had a bodybuilder, a big guy, come in here once and after about 30 minutes, he just walked,” he says. “He said, ’No, this isn’t for me.’” In that instant, I long to do the same. Nevertheless, amid the terror is the little red glowing tip of curiosity. And the knowledge that I do not want to waste my money, or this opportunity. I’ll write with that. When will I ever get to do this again?

I drop my visor. Through the lens, smaller than an index card, the pieces of steel and table in front of me are dim, seen as if through really, really, really dark sunglasses. Which, of course, is what that lens is. With my right hand on the trigger and my left hand supporting the tip of the nozzle – so much closer than I ever expected to be to fire and molten steel – I press the trigger. The copper tip spits a fizzing white fire that crackles. Blindly – it’s dark, inside and outside the helmet, except for that bright white light – I circle the tip along the metal joints as instructed. And then I can see what I’m doing. Feel it. It’s raspy and propulsive, like the feeling of wood under sandpaper, an energy halfway between element and machine and animal, with a constant backward impulse I must learn to lean into, counteract, resist. Seven seconds, maybe eight, and I let go of the trigger, the spark goes out, and my classmates and teacher and I lift our hoods to see what I’ve done. It’s a thick molten puddle in the joint, cooling quickly from red to silver at the end I’ve just finished. And I want nothing more than to do it again.

Luckily, last night (night 2 of 4), I get my chance. Having purchased steel rods instead of rebar, my eyes full of glories like the work of Kelly’s friend Helen Denerly, I arrive at class raring to go. Joyously, we dig through Kelly’s collection of metal scraps. “How about this?” he asks, lifting an old green-painted gear. “For the base. And these curlicues for the roots.” Through his eyes, potential springs to life. Suddenly I too see creatures, roots, trees, living things in scrap. I see potential in chance and accident and available bits. And, under the guidance of teachers present and absent, my bottle tree starts to come to life. Nights 3 and 4 are ahead – more branches, every day.

* UPDATE 10/30:

The bottle tree is finished – and, after teaching a bit of PARADISE LOST relative to FRANKENSTEIN in Paideia that very day, I was inspired to make a snake to drape on its branch or wrap around its base, out of a scrap of metal and a bicycle chain.