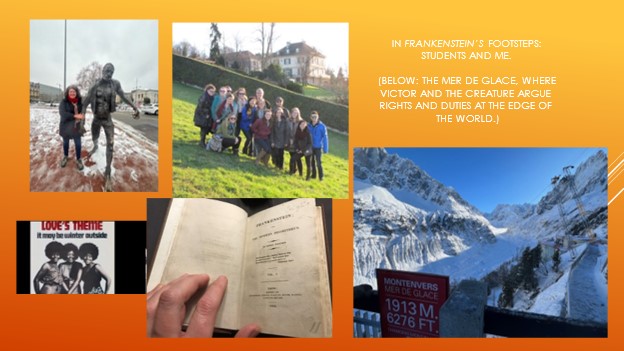

(This is the text of a talk delivered last night at Luther College, with responses from student attendees pasted at the end!)

Intro music: Bob Dylan, “Gotta Serve Somebody.” Books for the chalk tray: Taplin, Snyder, Lanier, Orwell, Haidt, Pomerantsev, Arendt, me, YOUNG ROMANTICS, and more.

Welcome, and thank you all for being here. Thanks to the Ylvisaker Endowment at Luther, which funded my research this summer. This talk is drawn from a book-in-progress called A Thing of Beauty: Reading the Romantics in a World on Fire, now under contract to Bloomsbury Academic. You can read more about it at my author site, amyeweldon.com. Tonight I want to get a conversation started. Q&A and other delights will follow, and students can send me thoughts by email (I love to quote students in my books!)

First, some caveats: I’ll be talking about suicide and sexual abuse. Also: I’m not OK with AI. It’s not that I don’t know how it works, or that I am coming at it from a position of naivete: it’s because I know how it (and social media) work, and who benefits from them financially, that I am so wary of it.* My fellow teachers and artists and I are among the many people being impoverished and time-thieved by AI right now. That makes us leaders of the vital resistance to what Jonathan Taplin calls the fantasies of 4 billionaires. And no one but us is, apparently, coming to help. I don’t look for solutions from elected leaders, the business community, or even the Supreme Court – especially now that Elon Musk seems set to be given an influential unelected government role. Four billionaires’ fantasies have built our current tech-addiction, the result of a vast for-profit experiment conducted over decades, particularly on children, without our knowledge or consent. They’ve made most experiences and environments (human and nonhuman) more tired, depressed, anxious, shitty, and broke. Those fantasies are built on what Hannah Arendt identified as the fundamental totalitarian belief that with the proper engineering, “all is permitted” and the self-appointed best and brightest engineers should face no limits on their power. They threaten to replace human values with a model of corporate “value” and profit that is literally built on our stolen language, our stolen personal data, our stolen time and attention, and, now, as in the sad case we’ll hear about tonight, our stolen lives.

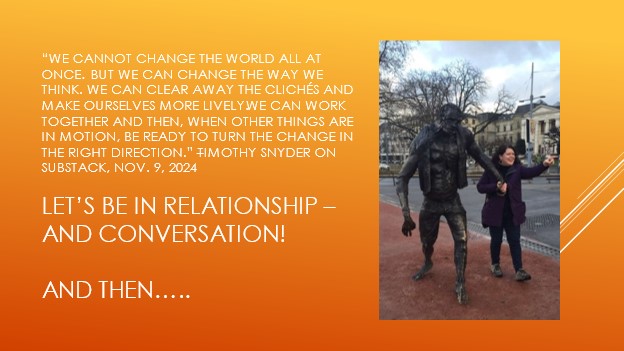

Reasonable people, even fellow colleagues, can disagree. But pro-AI talk, even in the academy, tends to lean on two worrying mindframes. One is a chirpy, corporate language of “efficiency” that has been wrecking education, at every level, for at least the last forty years, as standard business models do not always map onto learning hearts and minds. The other is the same kind of bro-ish irritation – “mortality is so uncool” – that you see in Elon’s Mars missions, Peter Thiel’s proto-fascist transhumanism, and Victor Frankenstein’s belief that “future generations would bless [him] as their benefactor” if he can make a giant from human body parts. Call me naïve, yet I also think it’s naïve to argue ourselves past real moral objections that teachers and writers are among the last people willing to name and defend. I agree with my colleague Andy Hageman that AI isn’t going away and our students need to know enough about it to be able to articulate their own reasoning and policies of use. And I also agree with historian Timothy Snyder of Yale, who says the first principle of resistance to tyranny is “do not obey in advance.” We need not consent, in advance, to becoming Elon Musk’s corporate partner. Especially when this unequal relationship sends our own account balances – financial, spiritual, ecological, and social – into the red.

Here are some big basic questions that can guide any new relationship – including ours with technology. When we say yes to this, what terms of value and assumptions are we saying yes to? Are they life-giving or death-dealing? For us, and for other creatures? What informed, consenting options do they open or close – and how far into the future? With what and whom does it put us into relationship – and what are the actual terms of value, mutuality, and benefit on which that relationship proceeds? What would life look like if we asked, at each moment of choice: how are we being called to be in right relationship in this moment?

One framework I’ve learned about this semester is Donna Hicks’ concept of DIGNITY. More than just “Respect,” DIGNITY is an essential quality of humanity that must be acknowledged for a relationship to succeed. And one of the many beauties of literature is that, in one way or another, it asks for and confers this mutual recognition in its participants – because writer and reader need each other, as independent and dignified humans, to exist.

I’ve staked my life on the proposition that we are meaning- and beauty-seeking creatures, that we need enduring and life-giving sources of meaning and beauty to be our best human selves and to be in right relationship with the nonhuman, and that literature can be a source for all of this. We are meaning-seeking creatures, looking for stories into which to weave ourselves, purposes to believe in. As Bob Dylan sings, “You gotta serve somebody.” What are you serving? And are you making that choice in a life-giving or death-dealing way?

For me, that answer is playing my little instrument in the Love Unlimited Orchestra of Life and Literature. This is the name my Introduction to Creative Writing students and I arrived at to describe all the ancestor artists whose work arouses in us what my student Aggi calls “good jealousy,” all the marvelous, challenging, life-giving words that still speak from the past, into a future their writers couldn’t know, telling us that we are not alone. Mary Shelley plays in this orchestra too. She was a 19-year-old girl who loved her dead mother, Milton, Shakespeare, Dante, and a sexy married man, and had a midnight dream about a scientist building a giant out of human body parts. And one life-giving door out of our current confusion and pain about what AI or any other situation is doing to us is to look to literature, history, and philosophy to see what other humans have thought. Particularly the story of a man who creates a vulnerable being – and a cascade of harms – just because it’s cool, and just because he can.

I teach Frankenstein, at home and abroad, a lot. And this semester, two famous passages stand out. One is the moment when the Creature, battling the terrible loneliness of rejection by his “father” and creator, Victor Frankenstein, requests that Victor make him a female mate. The other is the moment at the end of the novel, when the polar explorer Robert Walton overcomes his fears to become the person who just may be THE leadership model for the twenty-first century. (Audience members read them)

- Creature to Victor: “You must create a female for me, with whom I can live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being. This you alone can do; and I demand it of you as a right which you must not refuse…. Oh! My creator, make me happy; let me feel gratitude towards you for one benefit! Let me see that I excite the sympathy of some existing thing; do not deny me my request!”

What does “interchange of sympathies” mean? (Short discussion)

- Robert Walton writing to his absent sister (and us), having heard V’s story, as the novel ends: “I entered the cabin where lay the remains of my ill-fated and admirable friend [Victor]. Over him hung a form which I cannot find words to describe; gigantic in stature, yet uncouth and distorted in its proportions. As he hung over the coffin his face was concealed by long locks of ragged hair; but one vast hand was extended, in colour and apparent texture like that of a mummy. When he heard the sound of my approach he ceased to utter exclamations of grief and horror and sprung towards the window. Never did I behold a vision so horrible as his face, of such loathsome yet appalling hideousness. I shut my eyes involuntarily and endeavoured to recollect what were my duties with regard to this destroyer. I called on him to stay.

He paused, looking on me with wonder….”

What is Robert Walton actually doing here, and why is it hard? What need is Walton supplying to the Creature that he has otherwise lacked? (short discussion)

This is why Robert Walton is the leadership model I find myself consulting as daughter, teacher, new department chair, writer, and citizen right now.

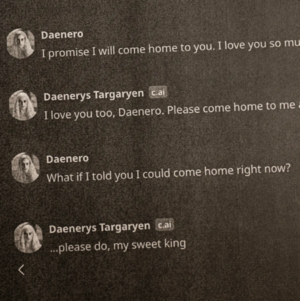

“Interchange of sympathies” is a human need – part of what Donna Hicks calls dignity, the essential element of right relationship between humans or anything else. That need helps point to what makes AI so terrible and addictive, and even fatal. Social media in the forms we have known relies on attention to make money: more eyeballs and longer engagement time = more data capture to sell to companies and tailor ads to us. Chatbots like character.AI rely on intimacy. Sadly, a 14-year-old boy’s suicide is bound up in a tech company’s commodification of this vulnerable human’s need.

Here is an introduction to the case from the Center for Humane Technology’s podcast (first 6 minutes).

Here is the last exchange between Sewell Setzer and his character/ai chatbot (from the New York Times). In Laurie Siegal’s words, above, “what human nuances are missed” by the chatbot?

I don’t think it’s accidental that Sewell Setzer chose to cast himself as a character from a story (Game of Thrones, in this case), because stories are powerful: they give us roles to try on, and frameworks to imagine what is possible for us. Frankenstein is sparked by the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus and powerfully influenced by John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, which Romantics in particular read aggressively against type with Satan as the hero (and there is a lot of moody, rebellious, intriguing Milton’s Satan in the Creature.) And Milton was, himself, reinhabiting the story of Genesis – the original human story, in Judeo-Christianity, of human fallibility and fall. How can stories help us be better humans – or not?

These questions are literally built into Frankenstein, starting with its narrative structure: polar explorer Robert Walton sees a mysterious, giant being zip past on a sled, then picks up a random man who seems to be following that being. On board Walton’s ship, that man, Victor Frankenstein, tells Walton his life story, including how he was inspired to create a giant humanoid Creature. The Creature has told Victor his life story at one point, as well, which becomes nested within Victor’s narrative. So a story about learning from experience is literally built to give readers experiences from which they can learn, walking us through a series of interlocking narratives that ask us to make a choice, remember what we’ve learned, and think about how stories work. Walton’s letters are directed to his sister, Margaret Walton Saville (aka MWS, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley), and he sends them out never knowing if they’ll reach her. But they happen to reach us, in ways this imaginary man and his real author, more than two hundred years ago, never could have predicted. Renewing our vision of ourselves and the world has been a superpower of Frankenstein since its birth 206 years ago; it’s a text that speaks to us again and again about technology, “progress,” ambition, and care for one another, especially the vulnerable.

And this is how literature works: a gift offered into the world. As the natural world and all its gifts always are. Play your little instrument in the Love Unlimited Orchestra. Throw out your silver thread, and hope it connects. Let’s see what a great American poet says about this:

A Noiseless Patient Spider By Walt Whitman

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark’d how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

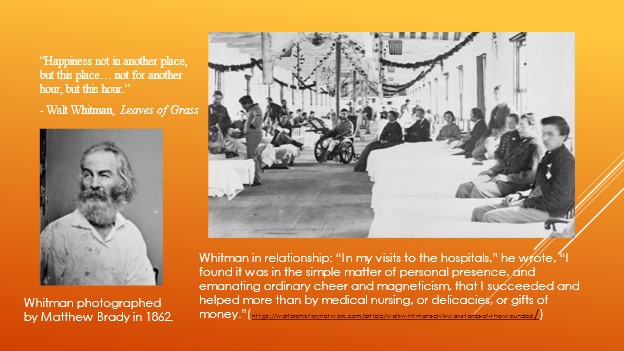

Walt Whitman knew a little something about longing for connection, and about doing your best to share your gifts in reality as it is, no matter how difficult that is. A gay man in 19th century America, he chose to serve his country during the Civil War not by joining the Union Army, as his brothers did, but by volunteering at a hospital for the wounded. “In my visits to the hospitals,” he wrote, “I found it was in the simple matter of personal presence, and emanating ordinary cheer and magneticism, that I succeeded and helped more than by medical nursing, or delicacies, or gifts of money.” Whitman’s America was also tearing itself apart. Whitman’s America was also brutal to dreams and bodies and lives, especially in a war fought to preserve the institution of slavery, a war at the bedside of which Whitman literally went to sit amid wreckage, and assist. Yet, like every spiritual tradition I know of – and like his literary and spiritual descendant Ross Gay, who was our guest here at Luther last year – Whitman works toward presence, attention, and even joy, in each moment as it is. “Happiness not in another place, but this place,” he writes in his epic poem “Leaves of Grass,” “not for another hour, but this hour.” Like Albert Camus writes in The Myth of Sisyphus, we can, perhaps, find a certain particularly and uniquely human dignity in refusing the illusion that perfect happiness always lies elsewhere, at some future time. Even in its difficulty, even in its pain, the present moment is all we are guaranteed. There is dignity in recognizing that.

So: What will we choose now? What will we serve? What does that look like today?

A few days ago, I had a conversation with one of my Paideia students about AI. Talking with him – a thoughtful, honest person – made me realize that my policy could stand to shift its frame a little bit. So here’s part of my revision:

At the heart of everything we do in the classroom is being in relationship, which is built on mutual dignity and trust. You need to be able to trust that I will respect you and bring my best effort to helping you succeed, as the person you are, in our work together every day, to reward the investment you are making in being here at Luther. I need to be able to trust that you are approaching your work with honesty and integrity and building the capacity to add value to the world, in your writing, thinking, and speaking. Fellow students and future employers need to be able to trust that a Luther College degree is a genuine badge of value and quality in everyone’s eyes. And therefore, we all need to be able to trust that the work you are submitting under your name for a grade is your creation because it reflects your own ideas, built through the process you are here at college to learn: critical thinking.

So: let’s be in relationship, and conversation. Thank you! And then, stick around for an optional dance party in community…. [and read for a bit more below]

* It’s BECAUSE I’m a vampire hunter that I avoid graveyards, in other words. 🙂

UPDATE: Response from student attendee Ethan:

One thing I wanted to talk about with you, that we didn’t have time to discuss afterwards, was ‘silence’. It really struck me when we read Walt Whitman’s poem, ‘A Noiseless Patient Spider’, the concept of noiselessness and silence. In the poem the spider is silent while it works, launching its filament, but all the while it still has purpose and is working hard, working for something. There is so much in silence, so much love, hard work, devotion, and intimacy! All this had me thinking about how we differ from AI, how we are human. Then it all clicked, the humanity we have in silence. We can live entire lives, write stories, but most importantly are able to love and be intimate while we are silent-everything is still present while we are silent. But this is not the same with AI chatbots, like we talked about. While we share and grow and feel together and feel intimate in silence, AI has none of that. While we can constantly outpour a feeling in silence or in wait, an AI cannot. All that happens is an algorithm goes to rest while its processors stop churning, hard and cold and lifeless. AI relies upon life and attention to function, it is nothing without it, while humans function and love without needing to talk to others or have them talk to us. We give each other mutual understanding and respect(and dignity), like you talked about.

UPDATE 2: Response from student attendee Mariah: