Bread Loaf Environmental Writers Conference, Ripton, Vermont

On a hillside in Vermont, at the end of a gravel road, a wooden cabin near the treeline. Four apple trees. A meadow alive with butterflies, tall buttercups, and the low intent fronds of wild parsnip, which will flower by August in skin-blistering yellow stalks three feet high but now, in the first week of June, are small enough to dig up and roast. A wild parsnip root is the same one you’ll find in your grocery bin. Tug it forked and muttering out of the ground, smudged, begrudging, sweet between the teeth. It’ll eat.

Inside the cabin, a kitchen just large enough to turn from stove to sink and back. Open shelves containing a tidy row of glasses, a blue and red Maxwell House coffee can, a 7Up bottle, biscuit tin, set of red and white Wood & Sons “English Scenery” teacups and plates with tiny cottages and trees, with paths leading out of sight through miniature worlds. A roasting pan dark with old scrubbed-away grease. A single knife upright in its rack. And, on the wall, a black telephone. A rectangular black wall-mounted box with two bells, where the sound comes in from the rest of the world. A heavy receiver with a slim waist, comfortable to the hand, and a bell for ear and mouth with six black holes in a perfect circle. The sound comes in from the rest of the world. The sound leaves this hillside in Vermont to go anywhere.

Lift that phone and savor its weight, the tensile spring of the cradle as it hefts the black receiver toward your ear and mouth. Objects can express satisfaction in a job well done, the job for which they’re made. Here on this wall this telephone listened to a poet’s voice. The poet listened to the wind in the trees outside, the scratch and mumble of a woodchuck in the rhododendron bush, the stretch and snap of roots growing invisibly underground, outward, into the dark, strengthening each tree in its reach for the sky. Each birch has a child to swing it, to climb down its length until with a satisfied sigh the tree whips back and tosses the delighted child into the air with a whoop of joy, a tensile leap of sound into the wind, a poem committed with a tree and the sky and one’s entire body.

Outside in that meadow is an upright lyre-shaped cradle of cobweb strung eight inches off the ground between two stalks of grass. It’s alive with wriggling larvae, caterpillars of something that’s surely ready to hatch some wings. A scientist might confirm that they’re tent caterpillars, unromantic pests that will munch their way through rhododendron leaves or aspen leaves or birch leaves or anything they can get. The poet might have hunkered down to eye this and then stood up just as a breeze caught the slim aspen next to him and sent its thousands of leaves quaking, fluttering, wringing their hands to praise the sky in palm and wrist and open, open, open hands. Lyre, he might have mused, and then another poet’s words would blow in to lift his own voice into speech, alone on the side of that hill: Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is. When one poet remembers and speaks another’s words, they are together on that hillside in Vermont, with its caterpillars and butterflies and small things nosing through the grass and aspens ecstatic in praise. No matter how many years have come between.

Tensile spring and heft. World translated into voice and hand and blood, and thus through time. These are what a poem has. These are what a poem does. These are what a poem is.

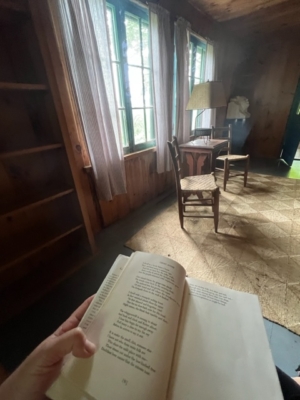

In the front room of the cabin, two woven-seated chairs, faded curtains of blue-striped ticking framing a view of a tree-covered mountain, green hazing away into blue. And a book of Complete Poems with a green cover and an etching of a farmer at a plow, leaning into the wind. That book falls open in the hand, right here:

GHOST HOUSE

I dwell in a lonely house I know

That vanished many a summer ago,

And left no trace but the cellar walls,

And a cellar in which the daylight falls,

And the purple-stemmed wild raspberries grow.

O’er ruined fences the grapevines shield

The woods come back to the mowing field:

The orchard tree has grown one copse

Of new wood and old where the woodpecker chops;

The footpath down to the well is healed.

I dwell with a strangely aching heart

In that vanished abode there far apart

On that disused and forgotten road

That has no dust-bath now for the toad.

Night comes: the black bats tumble and dart.

The whippoorwhill is coming to shout

And hush and cluck and flutter about:

I hear him begin far enough away

Full many a time to say his say

Before he arrives to say it out.

It is under the small, dim, summer star.

I know not who these mute folk are

Who share the unlit place with me –

Those stones out under the low-limbed tree

Doubtless bear names that the mosses mar.

They are tireless folk, but slow and sad,

Though two, close-keeping, are lass and lad,–

With none among them that ever sings,

And yet, in view of how many things,

As sweet companions as might be had.

In the plain room smelling of cedar and mothballs and a hundred summers the poem asks to be spoken, and spoken again. The sounds echo, rebound, graceful, rueful, sharp. Like wind. Like birds and woodchucks among the trees, busy about their own work. In the hand, the book is heavy, tensile, soft. Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is. On the mantel of the stone fireplace, a short thick horseshoe – perfectly sized for a sturdy Morgan mare pulling a plow across a field like this, leaning into the wind – rests upright. In a voice almost too soft to hear, it speaks: Good luck.