One week ago, likely-not-for-much-longer British PM (and probably-soon-to-be-gratefully-reverted-hedgie/tech-bro) Rishi Sunak left the 80th anniversary D-Day celebrations at Normandy early to return to London and prerecord a TV campaign interview. Footage of that moment shows the host murmuring thank you for being here. Just back from Normandy, Sunak says. “It ran over.”

Offense piled on offense, ridicule upon shame. LBC Radio’s James O’Brien and his callers give a good sense of the particular hilarity, scorn, and pathos it sparked. “This is typical Tory callousness,” said one, his voice shaking, “they genuinely don’t care about people.” Later, after the ITV footage emerged, O’Brien rightly mocks Sunak: “It went long! Bloody veterans, banging on about the war!” Who made this decision, he asks, that a sitting British Prime Minister should go home early from the 80th anniversary of D-Day (leaving two politically damning photographs behind?) Especially since this may be the last anniversary living veterans will attend? How? Just – how?

Maybe because Sunak is, at heart, a wannabe tech bro. And for a tech bro, joylessly “optimizing” each day, sticking to an itinerary, and fawning over Elon Musk is all part of the overengineering of career and life that can “make us immortal” – neglecting the values that, morally, actually can. Maybe Rishi Sunak, like all those tech bros who don’t understand why Scarlett Johanssen is upset about AI ripping off her voice, lacks empathy, or the political skill to fake it. I try to understand. I try to empathize. Because that’s what separates a normal person from a tech bro: empathy. That fundamental gear that makes a human heart human, that thing at which it’s easy for anyone to fail. Failure. Humility. Mortality. All sources of empathy. Yet true tech bros regard empathy as weakness. Wasted time. Insufficiently optimized uses of one’s attention and one’s four thousand weeks of life. Reward-less, redundant games for losers. Losers who have failed to optimize their lives on Earth. Losers who balk at leaving our one wild, precious, inefficient, precarious Earth behind. Losers who, in Wendell Berry‘s words, spend lives on things that “don’t compute.” Caring. Teaching. Writing novels that may never be published. Taking the impossible – marvelous, tragic – risks that connect us with other people in ways that might be remembered after we die.

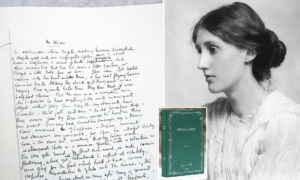

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925) takes place on a single lovely day in London in June (right about now!) in 1923, when the air is fresh “as if issued to children on a beach” and the sparrows are singing and a plane is skywriting a toffee ad and the shops are full of flowers. Two strangers – Clarissa Dalloway, fiftyish socialite and wife of a Conservative MP, and Septimus Smith, a shellshocked First World War veteran twenty years her junior – pursue, like birds, never-quite-intersecting paths through a day that will end in a very different place for each. But “plot” isn’t really the point of this book. As described in her essay “Modern Fiction” (1925), Woolf is after something bigger:

Look within and life, it seems, is very far from being “like this”. Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad impressions — trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come, an incessant shower of innumerable atoms; and as they fall, as they shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday, the accent falls differently from of old; the moment of importance came not here but there […] Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end.

And “luminous” is just what this awareness is. Life isn’t just marching down a well-lit street from one bright spot (or “optimized” success) to another, it’s moving through the world surrounded by and immersed in the halo of your own irreplaceable consciousness. Chasing a form of beauty, as every character in the novel is. Looking into the void, as every character in the novel is. If you’re lucky, your penumbra of light may touch, or overlap with, someone else’s. Mrs. Dalloway has so much – a husband who adores her, an adolescent daughter who takes her for granted, a host of acquaintances and old friends and neighbors, a rich and unpredictable store of memories – and yet she feels “odd affinities” with “people she had never spoken to.” Whirring through London in an open-top bus with her onetime love Peter Walsh, she exclaims “she felt herself everywhere, not ‘here, here, here;’ and she tapped the back of the seat; but everywhere:”

It ended in a transcendental theory which, with her horror of death, allowed her to believe, or say that she believed (for all her skepticism) that since our apparitions, the part of us which appears, are so momentary compared with the other, the unseen part of us, which spreads wide, the unseen might survive, be recovered somehow, attached to this person or that, or even haunting certain places after death. Perhaps – perhaps.

Significantly, this comes two pages after Septimus’s suicide, which readers have just been stricken by but Mrs. Dalloway hasn’t (yet). Oddly, this makes us feel seen, consoled. Maybe our attachment and grief for Septimus – like the spider threads in Woolf’s imagery, like the roots of her flowers, like the luminous penumbra where two light-filled lives and auras meet – are connecting somewhere with him. With Woolf. With each other. Perhaps – in a novel – Septimus can survive. He can come back to life in each reader’s living mind, on the page written by a genius who walked into the River Ouse in Sussex during a second great war during which she feared she was “going mad again” and would lose the thing most precious to her – the ability to write.

Perhaps – perhaps.

Right now, in my Medicine in Literature course over Zoom, a dedicated student and I are reading Mrs. Dalloway together. (It’s going really well.) “I’ve never read a story like this,” he said, “that walks you through the demise of a whole human being. Stories are usually like Marvel Comics movies – a triumph. But life isn’t. Not always.” As Clarissa says, and my student agrees, you can’t say, of anyone else, or yourself, I am this, I am that. People are gray, not black and white. And through imagining other lives, a novel helps you understand this truth.

Today we talked about his job interviews and the questions he was asked: Describe a time when you contributed to a team. Talk about a difficult time you had with a co-worker. Tell us about when you had to refer to a procedure to solve a problem. Every single one of these is basically about empathy. Can you take a genuine interest in other people, imagine and speak to their needs? By asking us, literally, to rent (imaginary) strangers space inside our heads, novels show us how to do that.

So do historical documents like Siegfried Sassoon‘s “A Soldier’s Declaration,” read before the House of Commons on July 30, 1917, just before the Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). As my student is quick to spot, Sassoon could have been describing Septimus Smith’s betrayed idealism when he says, “I believe this War, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow-soldiers entered upon this War should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible for them to be changed without our knowledge, and that, has this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation.”

Crucially, Sassoon says a lack of empathy betrays soldiers too: “On behalf of those who are suffering now,” he says, “I make this protest against the deception which is being practiced on them. Also I believe that it may help to destroy the callous complacence with which the majority of those as home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realise.” One of the veterans interviewed at the 80th-anniversary D-Day ceremonies expressed his disappointment in Sunak’s departure by saying, “So many of the politicians now have never served in the military – they don’t know what it’s like.” And – shamefully for politicians – they lack the empathy to imagine it.

Today we talked about the end of the novel, the place where Septimus gets a funeral, of sorts. His terrible doctor and his terrible/pitiable wife (“in grey and silver, balancing like a sea-lion at the edge of its tank, barking for invitations”) come late to Clarissa’s party because (drawing her aside, in hushed voices) her husband just had an emergency, a young man who killed himself. And at the earliest opportunity – leaving her guests, including the Prime Minister, downstairs – Clarissa goes to an empty room to be alone with this. To imagine it. To give it what philosopher Hannah Arendt called “a claim on [her] thinking attention.” To let it weigh on her. Even though she’s never met that dead young man, and this is her party she’s been preparing all day, and the Prime Minister is downstairs, she takes a moment to stand next to this stranger in the imagined space of his life: “She had escaped,” she thinks, in the heart of a long passage of contemplation, vivid imagination, empathy, and gratitude. “But that young man had killed himself.” And he comes to life again in her imagination – and ours. Because, with empathy, she allows his life to become real to her.

This is what any of us – particularly those who were not there – should not have to be told to do on the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HaMnwZW1GAM

BONUS:

** If you read Mrs. Dalloway and love it, as I do, you may be interested in what develops every time I teach it: A Mrs. Dalloway playlist. (Can you match the character with the song? 🙂

“Mustang Sally” by Wilson Pickett

“Once in a Lifetime” by the Talking Heads

“Don’t Dream It’s Over” by Crowded House

“The People That You Never Get to Love” by Susannah McCorkle

“Flowers” by The Emotions

“Sweet Freedom” by Michael McDonald

“Before I Let Go” Maze feat. Frankie Beverley

“I’m Not In Love” by 10cc

“Our House” by Madness

“Our House” by Crosby Stills Nash & Young

“With or Without You” by U2

“Someone Saved My Life Tonight” by Elton John

You never cease to amaze me. This rates brilliant.