It’s not often that a movie lives up to its press, but “The Favourite” does – and more. It also reanimates a story coming to life in front of me, right now, in the first six-volume history of England written by a woman, published around the American Revolution and resting on my desk in the Rare Books Reading Room of the British Library, spine-cracked and secured with a cheesecloth string but very much alive.

First, the film. Refreshingly unscared of its own weirdness, “The Favourite” explores what power and weakness do to people, and how unhealed wounds tip this fatal combination over a fatal edge. Its matter-of-factly freaky view of history feels right to me in these days of Brexit and border walls. Maybe I’m just a mid-40s academic who comes pre-loaded with an appetite for oddity and an idiosyncratically stocked sensorium of the past, but I loved this film. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf’s remark about Middlemarch, “The Favourite” is a movie for grown-up people.

From the first moments, “The Favourite” stamps the lived textures of the past onto the screen as so many other films – including, regrettably, the recent “Mary Queen of Scots” – do not. We begin in 1708, that gap between the Civil War and the madness of George III that most of us forget. From shit-smell in mud (“they call it political commentary”) to hand-scorching lye in a kitchen that’s recognizably Hampton Court Palace to Wedgwood-frosted cake and even a poker-faced “Soul-Train”-ish minuet, the film draws us into its world with fluency and conviction. You feel and smell and hear this place: reverberating steps and slamming doors, a shotgun-kick, a wheelchair rumbling over creaky floors, the weight of dresses and trains and all their padding, frail bodies dragged and gouted and bedridden and used. Sound and costume and music and hair all feel both of their time and slyly hearkening to ours. (Whoever chose the song playing over the final credits – sorry, no spoilers – has earned their Oscar just for that.) True 18th-century geeks may even detect in the film’s poster a nod to Mary Toft. As in one of my all-time favorite films, Federico Fellini’s “Amarcord,” each image feels charged enough with meaning, in the wordless way good images can be, to earn its place.

The plot sounds simple: ailing, insecure Queen Anne (Olivia Colman) and her “favourite,” the Machiavellian Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough (Rachel Weisz) find their relationship disrupted by the arrival of the Duchess’s young cousin, Abigail (Emma Stone.) Each of the three complex women is both sympathetic and deformed. But how? By the status-madness of Court? By the men whose open disrespect perversely feels more honest than their flattery? “The Favourite” doesn’t pretend to have answers. Instead, it sets us down in a richly drawn world with complex people and, like the Enlightenment God, stands back to watch. Each object, action, and detail (even the never-quite-explained ones) build meaning. The lavish dresses, coats, wigs, and makeup mean everyone’s in costume, which only the men can safely discard. (Brilliant designer Sandy Powell also dressed Tilda Swinton in “Orlando.”) Yet “The Favourite” doesn’t play villain-and-victim with gender. Men are casualties of this world too; by the time young Samuel Masham (Joe Alwyn), falls in love (almost in spite of himself) with who Abigail really is, she’s left him far behind. Watching her harden into the woman she thinks she’s always wanted to be, you’re chilled by the shades of old legends about lavish dresses that poison their wearers (the jilted Medea’s gift to Jason’s new wife), or Midas’s gift-turned-curse. “The Favourite” understands those stories too.

Medea and Midas feel right to invoke in a movie about the sterility – using this world in the most global and spiritual sense – that particular combinations of power and weakness can bring. You won’t see any children in this world, except Queen Anne’s lingering grief for a loss handled just right and the occasional preteen footman bullied around in his adult wig. Seeing woman after woman in stiff-fronted dresses, their bodies pushed into ostensibly alluring shapes but seldom experiencing anything like pleasure or freedom (sex in “The Favourite” is usually more about manipulation or need), I was reminded of how the Elizabethans joked that their own board-stiff stomachers “kept flat the bed wherein the babe shall breed.” This overthought, inward-looking world, built on status and pumped up by war, is no place for babies. And – as certain photos and articles keep reminding us – women aren’t only the Helpless Victims of Oppressive Systems but often the active builders and servants of those systems. Plain old human self-delusion knows, as Catherine Macaulay might have said, no sex.

I came to Catherine Macaulay through the arrestingly world-weary portrait (above) in London’s National Portrait Gallery and through Mary Wollstonecraft’s shout-out to her in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). As a self-made bluestocking on the loose, Wollstonecraft was grateful for foremothers she could, in her word, “respect,” calling Macaulay “the woman of the greatest abilities, undoubtedly, that this country has ever produced” and regretting openly (although not quite in these words) that Macaulay died before she could read A Vindication. Like Wollstonecraft’s, Macaulay’s voice on the page is forward-leaning, swift, and unabashedly intellectual. Like Wollstonecraft, she directly engaged with Edmund Burke and wrote about women and education. And like Wollstonecraft, she was satirized for her “unorthodox” sexual behavior. In 1778, aged 47, widowed mother of one daughter, she married her second husband, the twenty-one-year-old William Graham, a marriage lasting until her death 13 years later at age 60. William Graham was the younger brother of James Graham, inventor of the sensationally quackish “Celestial Bed,” a round electrified platform advertised as a way to help infertile couples conceive. At one point, James Graham offered women the opportunity to pay to enjoy the Celestial Bed in the company of Charles Byrne (1761–1783), the “Irish Giant,” subject of a great novel by Hilary Mantel, whose skeleton students and I have visited in the Hunterian Museum just a few blocks away and who appears in chapter 2 of my long-ago dissertation. Damn, I love the eighteenth century!

I’m still a Catherine Macaulay novice, but I’m already hooked. Read her and you hear that same bracing grown-ass-woman-ness you find in Wollstonecraft at her best, in Jane Austen’s Persuasion (by far her best), and in Carmen McRae’s “I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry” from her 1964 album Bittersweet, played in my Romanticism class as our Persuasion soundtrack. She’s a small-r republican who follows truth where it leads her, regardless of party lines. Her voice has a clarity and bite common to good political writing in any age. And like Wollstonecraft, she’s not afraid to call it as she sees it. Here’s her take on the Reformation:

The view of Henry the Eighth was to gratify his resentment against the Roman Pontiff, to enrich his coffers with the spoils of the clergy, and to render his power completely despotic by the union of the eccelsiastic with the civil sword. These pious views have been religiously followed by his successors; church government, instead of being new modelled on a plan proper to preserve the freedom of the constitution, and the morals of the people, is rendered a mere ministerial engine; the spiritual kingdom of Christ, a subordinate limb of the state politic; and the regular teachers of Christianity, the professed creatures of government, and the base instruments of wicked policy. (3)

About the Tories of the time, she’s equally unsparing:

This political sect may justly be termed idol worshippers; they make a deity of human power, and expect particular benefits for their servile offerings. They look with malignant eyes on democratical privileges, merely because they affect the happiness of subjects in general; they grant power to the sovereign as misers lend money, with the view of illegal interest; and willingly subject themselves to the insolence of superiors, on the hope that they may have it in their power to return the insult on those whom they regard in the light of inferiors. (31).

And:

The interest of religion, my friend, though always the pretence used for carrying on ambitious views, is always deserted when it interferes with the real motive for action. (104).

And:

The empire of the sea, my friend, is attended with such important commercial advantages, and is so strong a security against the ambition and insolence of foreign enemies, that it is impossible that any sovereigns can be mistaken in this grand point of policy; but where a people, through idleness, ignorance, and corruption, pay no attention to the concerns of the public, and leave the important interests of society to the care of individuals, these important interests will ever be sacrificed to the lusts of those individuals; this, in a very peculiar manner, has for many centuries been the fortune of England. (125).

It’s a thrill like no other when you can read the long-s print of 250 years ago bitten into the page in fading ink, then look up blinking into a suddenly strange present, asking: What year is this again?

So imagine my joy when I came to her treatment of the same events “The Favourite” has dramatized. I’ve regularized the long s’s here:

The uncertainty of human greatness and felicity is an observation which lies level with every understanding, and is the hackneyed topic on which every moralist largely expatiates; but, surely, my friend, that grandeur which depends on the favor of princes has the least permanency in it of every other earthly blessing.

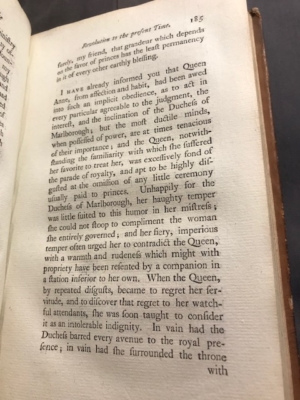

I have already informed you that Queen Anne, from affection and habit, had been awed into such an implicit obedience, as to act in every particular agreeable to the judgment, the interest, and the inclination of the Duchess of Marlborough; but the most ductile minds, when possessed of power, are at times tenacious of their importance [there’s that power-and-weakness combo again!]; and the Queen, notwithstanding the familiarity with which she suffered her favorite to treat her, was excessively fond of the parade of royalty, and apt to be highly disgusted at the omission of any little ceremony usually paid to princes. Unhappily for the Duchess of Marlborough, her haughty temper was little suited to this humor in her mistress; she could not stoop to compliment the woman she entirely governed; and her fiery, imperious temper often urged her to contradict the Queen, with a warmth and rudeness which might with propriety have been resented by a companion in a station inferior to her own. When the Queen, by repeated disgusts, began to regret her servitude, and to discover that regret to her watchful attendants, she was soon taught to consider it as an intolerable indignity. In vain had the Duchess barred every avenue to the royal presence; in vain had she surrounded the throne with her creatures and dependents: these very dependents seized every opportunity, which her violent temper and uncourtly manner gave them, to supplant her in the affections of the Queen; and she at length experienced, that a passion for power is common to all characters, and that love itself is not so strong an incentive to breach of trust as ambition.

Whilst the Duchess of Marlborough, in full assurance of the entire possession of the Queen’s favor, continued a conduct little calculated either to recover, or even to preserve her mistress’s affections, Mrs. Masham, a distant relation of the Duchess of Marlborough, whom she had placed about the person of her mistress in the office of woman of the bedchamber, was every day undermining her benefactress in the favor of the sovereign.

Had the Queen been kept under less restraint, perhaps Mrs. Masham might have been contented with enjoying the personal consequences which follow the favor of princes; but without entirely breaking the fetters in which her mistress was held by the Marlborough family, those doceurs would be wanting which you know, my friend, render the friendship of the powerful peculiarly valuable.

In this situation of things, Mrs. Masham found little difficulty to procure the kind assistance of a skilful advisor and abettor. (184-187).

Enter Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford (played by Nicholas Hoult in the film.) Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, is edged out. And she doesn’t take it well. Macaulay again:

One must, my friend, be thoroughly acquainted with the character and disposition of the Duchess of Marlborough, to have an adequate idea of the rage which possessed her soul on the conviction that the Queen had presumed to give to another that favor which she had once so fully enjoyed herself, or that a dependent of her own should have the insolence and ingratitude to have attempted the supplanting her in her mistress’s affection: in this tempest which rage had raised in her mind, she raved at Mrs. Masham, she expostulated with the Queen, and this in a manner as impetuous, though without the tenderness which often accompanies the upbraidings of a jealous lover (189).

This is as direct as Macaulay ever gets about the possibilities of “friendship” that the film develops in more detail. And while not an expert here – I’m also reading Ophelia Field’s The Favourite and am not far enough along in it to know what use if any she makes of Macaulay – it rings true to me. Methodical and orderly, she earns the uptick in emotional interest here with long, long passages just before it recounting the details of treaties between England, Ireland, and Scotland. She’s not here to gossip, but she’s not going to leave things out.

Before delving back into Macaulay today, I emailed my students to encourage them to acquire British Library reader’s permits and experience such portals to the past for themselves. Wollstonecraft regrets openly in Vindication, I said, that she never got to meet Macaulay, yet now, on this table and in my own mind and heart, their books are together, and alive. There is really no feeling like communing with the past via the texts of the past in their original forms. Something matter-of-factly vigorous and lively about the experience is irresistible to me, and not only since Wollstonecraft lived, worked, was married, and was buried less than 1/4 mile from this spot — which became a site of pilgrimage for her daughter, Mary Shelley, and for my students and me. I feel blessed to have the opportunity to post this piece from the British Library reading room, to be encouraging students here too, and then to shut the laptop, turn back to the stack of books to my right, and keep reading.

FABULOUS IN ALL REPECTS. REFRESHING.