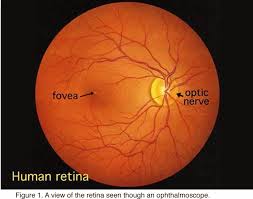

On an ordinary November afternoon I sit on a chair in my eye doctor’s dim exam room, chin in the camera-machine, straining not to blink against the stinging dilation drops leaking through my lashes. A white flash jolts straight to the back of my head. And then, there on the screen are photographs of my own two eyes as I can never otherwise see them: rosy, beige-pink retinas with elegant intersections of arteries and veins arching from bottom to top, meeting and twining in the middle before going on their separate ways – bringing the blood, taking the blood away. The macula is a deeper rosy beige, a dark concentrated point like a pregnant woman’s nipple. And in the center of each retina a white light blazes: the optic nerve, which carries the images formed in light directly to my brain.

Overpoweringly the images of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling come to me – Adam’s flesh illuminated by the God who strains to touch it, whose robes are not so far away from this same color pink. The round shapes of the dome he made for St. Peter’s Basilica and the dome that Brunelleschi erected over the Duomo floor in Florence, where students and I have stood to gaze up and around and then at the fresco on the wall of sorrowing Dante stretching his hand toward Paradise – Florence itself – with Hell and Purgatory at his back. Dante struggled with how a God who loved us could have created a world in which we’d be born to fall, and then a hell to punish us for our sins in that same world and in the same bodies He had made, ostensibly, in His image. William Paley and Charles Darwin wrestled with whether bodies so intricately wrought as ours could have been made by a creator, by the actions of evolution over deep time, or some combination of both. When Haydn’s oratorio “The Creation,” musically illustrating the Genesis story, was first performed, audiences leapt to their feet and applauded when the quiverings and mutterings of the first orchestral phrases resolved into the burst of choral voices proclaiming, “Let there be light!” Let there be light: the ultimate example of word into thing.

Dante, Haydn, Paley, Darwin, Michelangelo: I am studying each of these artists and thinkers with first-year students this semester, wondering as we talk what they are seeing, what they are putting together in their own minds with the words on the page or the overhead-projected, glowing image of Adam and God (fingers almost but not quite touching) we gaze at all together. There is no way to know, completely, and that is as it should be.

I remember standing in the British Library and reading the words of an original copy of a Tyndale New Testament of 1526, a battered, hand-sized leatherbound book open to Matthew 7 in the case underneath me: “Care not therfore for the daye foloynge. For the daye foloynge fhall care ffor yt fylfe. Eche dayes trouble ys fufficient for the fame filfe day.” From teaching at a Lutheran school – and from Hilary Mantel’s novels – I know how long it takes a human body to burn, and how righteous are the motivations of those who light the torch. Tyndale burned ten years later for words on a page that need no translation to the literate sixteenth-century English layperson, or to me. His working brain and his busy hands made this object that carries human language for the divine across four centuries, unchanged. And I bear the image of his book in the brain that rides unseen in my own head, the patient brain waiting at the other end of that blazing-white optic nerve.

I have been to a human anatomy lab and held a human brain in my hands; I have learned that ears are one of the two most disturbing things for new dissection students to see. The other is hands. Eyes can be easier, I’ve heard it said, because in death the light – the light – seems to go out of them, but I don’t think I could ever find it so.

Staring at those two rosy circles on the optometrist’s screen, those photographs of the apparatus of my actual sight — which so resemble twin suns — I’m overwhelmed by the fact of all I am made of and caught up in and do not and cannot see. The flow of life that lit up Dante and Michelangelo and Haydn lights up me, too, flows into my brain and creates my memories and thoughts and decisions through reflections of light on the surfaces of things that this dot of white so bright it is beyond color conveys directly to my brain. In looking at the retina and the root of the optic nerve, am I looking at the source of thought, itself? Am I looking at the source of the human self, what it knows and stores in the brain and calls forth as memory? Am I looking at the raw material of my soul?

Encounters with the radically mysterious, the radically other thing, can derange us in ways that feel wondrous or painful, because they jostle us off our privileged and self-constructed positions at the center of the universe. They remind us that life is bigger than we can know, and that it is not about us. Yet avoiding any discomfort of spiritual or material kinds – as much as our culture urges us to do that, by consumerism, technology, and various other forms of self-help engineering – reduces our capacity for not only imagination and empathy but, simply, for existence. “To be fully alive, fully human, and completely awake,” says the great Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron, “is to be continually thrown out of the nest.” Thrown out of the nest – it’s a metaphor of disarrangement, of being nudged aside to make room for what else there is on the earth with us, which we are continually invited to see and to see again. If the baby bird is not eventually nudged out of the nest into a strange and initially forbidding world, she’ll never develop the muscles to fly or discover that she is not the only being in a world not centered on her. How rich our lives can be if we really consider this. And how different the art we make, and our treatment of everything else in creation, can look.

– from a book-length manuscript-in-progress.

One thought on “Let there be light.”

Comments are closed.