Wiping sweat, adjusting our sunhats in an historic heatwave, we stop at the site of the Cock and Hoop on Artillery Lane in the east London neighborhood of Spitalfields. It’s a shell of an eighteenth-century wall, window-arches of stone and empty air. A modern tower block (housing for the London School of Economics) is butted right up against the back, leaving an inches-wide gap between the old brick and the new. It’s insolent, odd, oblivious, a rude kid nudging his grandmother in an airport line. The new windows don’t match the spaces sketched for them by the past: look out your dorm windows and the old Georgian arches would cross your sight like badly fit glasses-rims slipping down your nose. “Façadism,” sighs our guide, a “creeping plague” born of legal constraints on developers who then vent their spite with resentful, bare-minimum buildings like this. Better than tearing it down? Yet. Facadism: the word stays with me. In that mismatched empty space between the eighteenth-century arches and the careless new construction hums what feels like the tragedy of our entire twenty-first century – and what we must overcome to see, and build, something better.

Named after the medieval charity hospital of St. Mary’s Spital (founded 1197), known for the murders described in Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five and, more recently, the vibrancy of Brick Lane, Spitalfields is a neighborhood I’ve previously known only from our guide’s excellent blog and books. Although gentrifying (like everywhere), it’s an energetic place, layered with the traces of refugee lives: Huguenot silk weavers fleeing France after the Edict of Nantes, which had protected their religious liberty, was revoked in 1685 (the phrase on tenterhooks comes from the metal “tenters” on which they’d stake their silks to dry in the sun), Jews who established shelters and soup kitchens, Muslims and Hindus who’ve sunk new roots here, street artists bursting with witty anger in these summer days of record heat and smartphone-dazed, street-clogging wanderers and Conservative political disaster. Nicholas Culpeper’s herb garden flowered on a site just around the corner from the Ten Bells, where Annie Chapman had her last drinks. Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church Spitalfields looms over the corridor of Brushfield Street. The Brick Lane Mosque occupies the former Huguenot Chapel, which was also once a synagogue; all three Abrahamic faiths have been present in this building. A sundial near its roof still bears the legend Umbra Sumus – We are only shadows. Lives and histories pass over this city like the clouds that even in this heat come and go. Celts, Romans, Saxons, Normans, Vikings. And, eventually, us. Whoever we are. We modern twenty-first-century travellers, looking for meaning and traces of something real below the glare of the hundred-degree day but so content with shadows, now. So content with facades. As if we had all the time in the world.

Maybe facadism is the name I’ve been looking for to describe the disease of the twenty-first century: our fatal contentment with the simulacrum, with the Instagrammable photo (mightn’t that be the real object of travel?), with the Disney ripoffs clogging Drury Lane and the Lyceum, with the sugar rush of fake emotion and fake political moods and fake historical memes. (What’s the Sunak/Truss contest if not Thatcher-facadism on a grand scale? What was Boris Johnson if not a façade of his own pseudo-Churchillian fantasies? And let’s not neglect the US’s own dumpster fire of a twice-impeached, riot-inciting former president, playing a poor person’s idea of a rich person on reality TV – can he even spell “façade?”) But as Andrew Marr points out, the monster is tapping at the window. That protective glass is not so thick. London (a mostly AC-less city) is in the 90s this week. Climate crisis, soaring inequality, political opportunism, wars rumbling on Somewhere Else (among the people meeting the Eurostar from Paris at St. Pancras Station are volunteers holding up signs to welcome Ukrainian refugees; when you, basically, share a continent with Ukraine, you don’t have the luxury of being bored with it), and a general sense that all the wheels, everywhere, are about to come off. It’s not as if we don’t know. And haven’t known. We’re out of time to pretend.

| Of course, ignoring the real in favor of the façade (as tourists and citizens) is not a new problem. In Childe Harold Canto IV, Byron, who perhaps invented the facadism of celebrity as we know it right now, described his own struggles to “repeople with the past” as he traveled through Spain, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland on a perpetual Grand Tour around the “haunted summer” of 1816. This was a self-dramatized but still, I think, genuine search for a spirit of authenticity and sacrifice that would kill him eight years later, bled out in a fever tent in Greece. He complained about bad travel guidebooks (“it may serve you well in your library, but not in your carriage”) and bad inns and food. He would have seen (and probably complained about) tourists using the Regency equivalent of a selfie stick: a Claude glass, a small mirror you could hold up as you stood with your back to a particularly enchanting scene to see it framed as it “should” be, in picturesque-landscape terms, on your wall at home. But he describes what at its best travel can do, re-enchant and re-animate a place (even a ruined or decayed place) with meaning in a living mind. Here he looks at Venice, which in his time had decayed from a crown jewel of maritime empire to the Las Vegas of Europe:

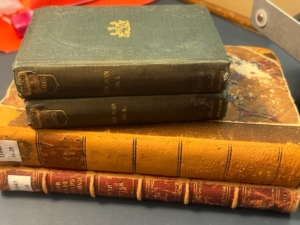

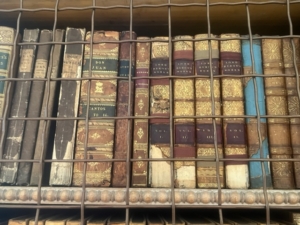

I can repeople with the past; — and of The present there is still for eye and thought, And meditation chastened down, enough; And more, it may be, than I hoped or sought.   This is every literary and historical traveler’s hope: come to a place with enough in your head to know what you’re looking at and enough spontaneiety to notice and be surprised by something new, to be taught by what’s actually there. You can find some meaning there, some hope that maybe time has left us with some purpose and beauty to hold onto, not only ruin. But what meaning is the twenty-first-century traveler – smartphone-addicted, selfie-taking, striving for the photograph that will remind us something really happened to us – bringing to, and looking for in, the places we see? More than a century after Byron, the famously wry Philip Larkin thought about travel too. In “An Arundel Tomb,” inspired by an actual medieval monument in Chichester Cathedral, he wonders what the long-dead “earl and countess” who “lie in stone” would see around them today: They would not guess how early in Their supine stationary voyage The air would change to soundless damage, Turn the old tenantry away; How soon succeeding eyes begin To look, not read. To look, not read: this is every traveling teacher’s nightmare. Because so much is at stake, for us and our world, in learning to read it properly. You build your best human capacities for the unknowable world that’s coming by looking. Up, around, down. Outside yourself. Not, at first, back inside. Because you build a self with something to say by experiencing the world, learning, having experiences and ideas about them. The you knowable by and reflected back at you by your social media is just a shadow, a facade, a flicker on the wall of Plato’s cave, precisely engineered to deliver maximum consumertainment rewards to your brain and maximum profit (for someone else) from your data. You become a person in the world – and build ideas about its past, present, and future – by engaging with it, learning about people and things and beings that are not you. Stories can still save us. Looking at what has been, and is, and is to come can save us. In Tate Britain, Hew Locke’s “The Procession” stuns and stops me in my tracks, with what is at first an eerie dreamlike presence and then, more gradually, the longer I spend with it, a curious one, a semi-welcoming one. I feel beheld in turn as I behold this parade of figures, an apocalyptic Mardi Gras funeral procession / jazz parade out of the colonial past and into the future. Every detail is rich, thoughtful, challenging. It is a titanic work of art. It will not let you merely look. It requires you to read. And think. And think again. Because the world in which you and these figures are standing together now is a world with a lot at stake. Reality is here. So is beauty. And I place my faith in them. In the midst of everything, they are here. Waiting to be seen. In people and the things we make and our power to remember and share. The original paperbound copies of Byron’s Don Juan in the family bookcases at Castle Howard in York. The red and pink Covid memorial hearts that cover the south wall of the Thames embankment between Westminster and Lambeth Bridges (“Mum,” “Granddad,” “Priya,” “Sondheim.”) Sarah and David, silver artisans, who are campaigning to have Whitby jet recognized as a semi-precious stone. Hasan, the London taxi driver who tells me about mastering “the Knowledge,” the mental map of the city you have to build for your licence: “yeah,” he agrees with pride, “it is like the Army.” The anonymous artist who carved the stone Chapter House stalls of York Minster with a hundred different, playful faces: cat and mouse, three-headed nun, wistful smiling boy, even if no one else would ever notice or care. Josephine Baker, a black girl from Jim Crow St. Louis who became an international superstar, and in that inner spark (where does it come from?) that rises and surfaces regularly in artists of every age, who filled her French chateau with unwanted children of every race. Osip Zadkine, making startling sculptures in a village in the middle of nowhere in southern France. Whoever grew the Quercy melons I ate, with thanks in advance for the seeds. Rev. Jennifer Smith, who greets a baptized baby from her pulpit in John Wesley’s Chapel with, “Welcome – it’s such a beautiful world.” The modest, deep delight of the Garden Museum, tucked away in Henry VIII’s old Lambeth Palace, where archaeologists descended into the burial vault below the church and brought up a 300-year-old copper bishop’s mitre and left it on the steps for us to see. In the tomb of three generations of John Tradescants, pre-1800-century garden nerds, carved with the seashells and stuffed crocodiles and exotic plants they loved: These famous Antiquarians that had been / Both Gardiners to the Rose and Lilly Queen / Transplanted now themselves, sleep here, and when / Angels shall with their trumpets waken men / And fire shall purge the world, these hence shall rise / And change this Garden for a Paradise.

On my last evening in the city I went to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where Captain John Smith (of Pocahontas fame) is buried, to see a concert: Ukrainian conservatory students, no older than 25, who have followed their art to London as the rest of their world overturns. Taking turns at an old grand piano with a squeaky bench, poised before the altar under the flaking plaster arches of this 550-year-old church, Yulia and Andrew (“in English it’s Andrew”) played what sounded to me like Liszt, Chopin, Debussy, and more. Last time I was in England – in 2019 – I saw Angela Hewitt at the Southbank Centre. And I have no doubt that Yulia and Andrew will follow her. They’re supported here by a charity administered by the tireless Father Nick Mottershead, a one-man dynamo of positive energy and total sincerity (being a priest is his second job!) The program costs approximately fifty thousand pounds a year. But Father Nick is undeterred. “As the national musician’s church,” he tells me after the concert, “I want us to be super-warriors” for the kind of beauty that can change lives, even in the face of war, right up the hill from JP Morgan and Amazon HQ. “I want to change the city culture by putting our pens down and recognizing: this is a blessed life.” Art and beauty: this is hope in the face of war and its upheaval. This is the shape given to human life, in spite of everything. This is trust in beauty, and in one another. And it is a spirit that will – in Larkin’s words – survive of us, and enable us to survive. Learning to read, not look, and to seek the real rather than the facade: this can change the world.

|