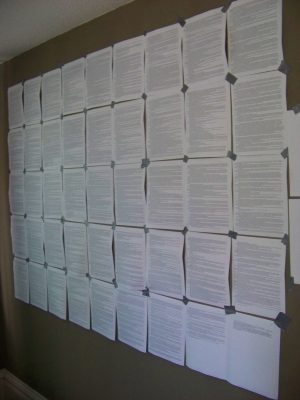

This is the whole manuscript of my novel-under-revision, printed out in 8-point type and hung up on my guest-bedroom wall. (Suitably redneck for my Alabama origins, the duct tape sticks to plaster where Scotch tape won’t.) “So that’s how novelists work,” said a friend on seeing this picture. Well, I don’t know about other novelists – especially those more skilled/experienced at this than me — but I do know one thing: in the same way as gardening, getting your hands and body involved in revising your written work clears out all kinds of intangible blockages, anxieties, doubts, and confusions, like the heebie-jeebies I was suffering from a post or two ago. A novel also is a plot of ground, both literal and imaginative, that you work over with your senses and your hands. Hanging the novel on the wall like this will allow me to “plug in” new scenes on smaller pieces of paper I can tack to the wall at the appropriate spot, and understand their positioning relative to the more important moments in the plot (marked by words to be scribbled in pink highlighter on the hanging-up pages: “kiss,” “shot,” “accident.”) I can hunker down to read one scene, stretch up to read another. I can see which scenes are longer and need to be shorter, or vice versa, where I have more and less dialogue. Any aerial view reveals patterns you just can’t see from the ground.

This is the whole manuscript of my novel-under-revision, printed out in 8-point type and hung up on my guest-bedroom wall. (Suitably redneck for my Alabama origins, the duct tape sticks to plaster where Scotch tape won’t.) “So that’s how novelists work,” said a friend on seeing this picture. Well, I don’t know about other novelists – especially those more skilled/experienced at this than me — but I do know one thing: in the same way as gardening, getting your hands and body involved in revising your written work clears out all kinds of intangible blockages, anxieties, doubts, and confusions, like the heebie-jeebies I was suffering from a post or two ago. A novel also is a plot of ground, both literal and imaginative, that you work over with your senses and your hands. Hanging the novel on the wall like this will allow me to “plug in” new scenes on smaller pieces of paper I can tack to the wall at the appropriate spot, and understand their positioning relative to the more important moments in the plot (marked by words to be scribbled in pink highlighter on the hanging-up pages: “kiss,” “shot,” “accident.”) I can hunker down to read one scene, stretch up to read another. I can see which scenes are longer and need to be shorter, or vice versa, where I have more and less dialogue. Any aerial view reveals patterns you just can’t see from the ground.

In years of teaching and reading about and working at my own writing, I’ve learned the subtle, surprising power of physical revision techniques, especially those involving scissors and tape. Like my favorite writer, Eudora Welty, I cut manuscripts apart along any “dividing lines” that seem natural (which can be paragraph, section, chapter, or thematic breaks) and rearrange them, trying on different sequences of order. (Welty used to spread her typescripts out on her dining room table in her Jackson, Mississippi home and pin them together like a dress pattern, an image I love.) I have hung taped-together sections of the novel in long strands from the doorjamb of my writing room, making a curtain to swish through like beads over a fortuneteller’s door. I have sorted cut-apart scenes by type and theme: which pile is biggest, and how does that tip me off to “what this project is really about” — one of the writer’s most important questions? Susan Bell’s wonderful book The Artful Edit is a great introduction to techniques like this. Example: consider waiting until you are done with a significant section of a long manuscript — maybe even your first draft of the whole manuscript — to print it out, because printing out and scrutinizing smaller sections can interrupt your momentum and immersion in the long project, casting you into the familiar revise-your-first-two-pages-one-billion-times cycle.

After hanging up these pages, writing a new scene and some notes, and going to my regular Monday-night yoga class, I re-tackled my newly carved garden plot: a week or so of looking at it from my upstairs window as well as the back door convinced me it needed to be bigger. So I got out my trusty, if quirky, old-school orange Ariens tiller ($30 from a friend, four years ago) and carved out an additional slice of ground, keeping the rounded shape but stretching it out. A little less grass to cut. And more vegetables to grow and preserve. Garlic. Fall bulbs: tulips, daffodils. I’m making next year’s plans already.

And those plans include some big financial moves: saving, investing. “One year from now, what will you wish you had done now?” is an immeasurably powerful question. Taking an aerial view of your projects and your life – where you are, where you are going, what is the overall shape and trajectory you want to achieve – can help you achieve any goal you can imagine.

Amy — your last several posts have been particularly inspiring. I really love reading your blog. 🙂

Thanks! I am so glad! Hope you are well! 🙂