He dressed himself in camoflage. Amid the wordless shock and horror and grief, that’s a detail that sticks. He dressed himself in camoflage and gathered his weapons — including Sig Sauer and Glock handguns and a Bushmaster .223 M4 carbine, purchased legally — and went to an elementary school. There he killed twenty children under the age of ten and eight adults, including himself and his mother.

Now he’s being added to the list of public places and schools where mentally disturbed young men with guns have wreaked havoc and grief. Columbine. Virginia Tech. Milwaukee temple. Gabrielle Giffords’ constituent meet-and-greet in Tucson. Movie theatre in Colorado. Shopping mall in Oregon. I have a feeling I am leaving something out. But I also have a feeling this list is long enough.

I think about the movie playing on screen in that theatre: “The Dark Knight.” I think about the climactic moment in superhero movies, when the soon-to-be-hero dons his costume and suddenly recognizes himself as the one we, the audience, have been waiting for too. Psychosis spins itself up out of narratives, casting its own heroes and villains and dramatic sense of what’s at stake. This morning the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooter dressed himself in combat gear before picking up those guns.

I look at this list again. And I am seized by a feeling that these young men with guns, trapped in the dangerous cells of their own minds, were and were not alone in there. Movies were flickering on the walls of those cells, feeding and being fed by disturbed fantasies, paranoias, loner fears and longings and distortions and dangers. And all those movies had the same character: the brave young hero in whom violence and trauma signals complexity, who solves his problems with violence, who seeks an external “enemy” to lash out against and transform himself into a man.

This is one of America’s and maybe the world’s oldest stories, a fantasy running all the way back to Joseph Campbell and the Crusades and Camelot, if you want to go that far. But twentieth- and twenty-first-century America have put an even darker spin on it, depicting violence not only as defeating one’s enemy but as defining oneself, learning who one is in an indifferent or inauthentic world. John Wayne and James Bond and Steve McQueen set archetypes of cowboys, good cops, and spies, rugged or sleek or glamorous or intriguingly vulnerable under a tough exterior. Clint Eastwood turned a .44 Magnum into a catch phrase. Luke the Jedi discovering the power of his mind became Bruce Willis became Batman and his modern incarnations. Even after Abu Ghraib, straight-up torture became acceptable for “horror” films from the unapologetic “Saw” franchise to “Fight Club” and the loathsome “V for Vendetta” (in which the aforementioned mysterious male hero torturing a beautiful young woman helps her “discover herself”), which I never want to hear another hipster defend. Any movie executive freely admits it: violence lures young men. Self-styled holy warriors from Al-Qaeda to Timothy McVeigh know it too. Here’s a narrative, young man, that makes your anger look noble and justified. Here’s a way for you to give your life shape and meaning, even if it ends in your death. Pick up a gun. Seize the controls of a plane. Build a bomb. Be remembered. Be honored. Be real.

Cinematized violence swirls through our world in an omnipresent stream, a black river to which confused and sick and sad boys come to immerse themselves and emerge — they hope — reborn as something like heroic. Authentic. Real. Pick up a gun and learn who you are: it’s a story available to anyone who has ever shot avatars on a video-game screen or has ever pointed a toy gun at another kid. Bang, bang. You’re dead.

And this dark river channeled through a mind that has shut out empathy, that has bent itself on destruction, that is bleeding unknown delusions and sickness into that black water flowing past, is fatal.

“The PA system was on at the time, so you could hear the shots,” said a teacher. Her students were as young as six years old. “It was a lot of shots.”

A four-year-old who was inside the school during the shootings wrapped herself around her sister’s legs once rescued and would not let go.

I’m a writer and a writing teacher. Stories, and analysis of stories, as limited as they seem in response to such a tragedy, are the way I have to make sense of things. I will never forget the days after the Virginia Tech shooting when my small college instituted new campus safety protocols, including discussion of what we professors should do if students in our classes became violent, how we should protect the other students in the room, how quickly we should rush to click the locks that had suddenly appeared on all our classroom doors. Within the creative writing community an additional anxiety flamed: how should we talk with students writing stories or poems about violence? What would creative license mean in a situation like this? That Virginia Tech shooter had been a young man writing violent stories in a creative writing class, spinning out fantasies on the page. It’s here, was the unspoken thought, seen on all of our faces in those days. It’s here.

With typical situational deafness, the pro-gun lobbies are rallying around such measures as allowing teachers to carry their own guns to school. This is just the cinematic fantasy from another angle: teacher as white-hat good guy (or more likely girl) who defuses the threat with Deadly Force If Necessary, trying not to catch (too many) innocents in the crossfire. But it doesn’t solve a damn thing, because it doesn’t challenge the terms of the conflict. It’s the same insistence on guns as the starting assumption for any sort of public life, and on violence as the proving ground for identity. It’s the same increasingly nonsensical unwillingness to wrench oneself out of a destructive, destructive story. (As a commentor on Gail Collins’ column about this tragedy pointed out, how is a teacher supposed to shepherd thirty adolescents into a “safe” corner while also returning fire?) Others sling pious statements that gun-law reformers should focus on mourning rather than “politicizing the issue,” as if this tragedy were completely divorced from human laws made by human actions and decisions. I feel the same sense of incredulity, listening to these “responses,” as I do when I listen to parents whinge about how they “really don’t like all those violent shows” their school-age children watch, but, “well, what are you going to do?” Turn off the damn television, that’s what. Take responsibility. Say no. Say this is not acceptable. Say it’s time we looked at the story we are living in and woke up to what is real.

Fiction writing students learn early to ask, “what is this story really about?” And “what’s at stake here?” I pray that in the days ahead we as a country will ask these hard questions and make decisions that will put guns out of reach of sick, confused boys. I pray for those who — just before Christmas, no less — are reeling from the death of a family member or friend or a child, which parents have described to me as the worst thing that can happen to you. I pray that we will step out of the seductive, swirling undertow of violence to walk on the difficult but hopeful ground of peace, and that we will let love and hope write us into a whole new story and a whole new world.

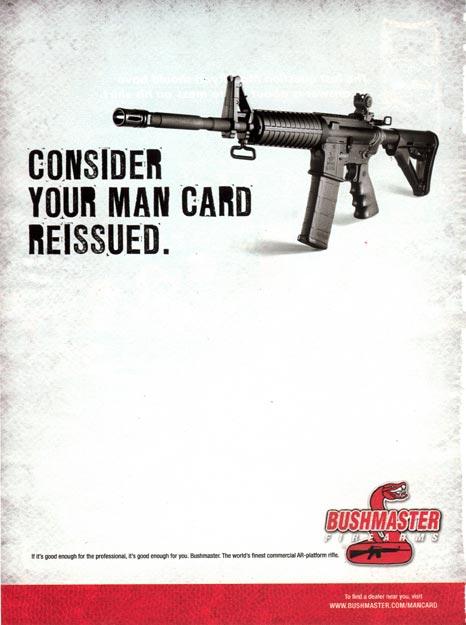

*** UPDATE Dec. 20: Courtesy of Jessica Valenti, the ad for the gun used in the Sandy Hook shootings.

And courtesy of Garry Wills, Catholic intellectual, a severe and welcome bit of context:

http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2012/dec/15/our-moloch/

Amy….you have really struck a cord here!

Thanks. Wish it was something I didn’t have to write. 🙁