“Experience enlarges the space for the self to swim in.” – George Eliot, from a manuscript in “Writing Britain” at the British Library.

A month of travel has left me with more than I can say, and more than I can put into words, even to myself, even as I’m settling into a fall sabbatical writing schedule again. Two big trips: one in quest of Keats, Byron, and the Shelleys with my mother – a powerful experience of making meaning together, now that we have to spend our lives 1100 miles apart – and one to the Aspen Institute’s Wye Summer Seminar, a journey into the self in many more, and more wonderful, ways than I expected. Isn’t this always the way when you travel? You find touches of the familiar and loved that endure from your own life and large and small encounters with the new – so many experiences and feelings that keep pressing outward, gently, on the walls of the self, which is always threatening to collapse in on you like a badly rigged tent, confining you in a small, closed, stifling space that comes, if you aren’t careful, to seem like your natural home. The old challenge is new and urgent all over again: how do I keep giving my life texture and forward momentum and depth, a gripping surface that keeps me from drifting inattentively through my days? How do I do and write the things that keep me moving out into this world, even when I am staying at home? New senses and spaces have opened in me, whole fields and woods: cleared or discovered, perhaps they were always there.

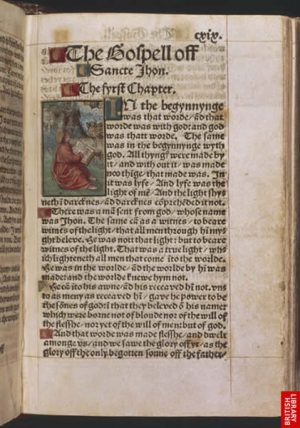

In January I will take fifteen students on a month-long trip retracing the steps of Mary Shelley and the Keats-Shelley circle through England and Europe, in and around the years of writing Frankenstein. This was the planning trip, starting in London. In the British Library, I wandered, overwhelmed with pleasure and awe, among manuscripts including Emily Bronte’s Gondal notebook and Charlotte’s draft of Jane Eyre (open to the “Gytrash” passage) and Virginia Woolf’s crossouts of lines from Mrs Dalloway and George Orwell’s notes for The Road to Wigan Pier, including a letter about what he was seeing – just like his prose, his handwriting is deft, sensual, and clear. With animated little stick figures (just like the ones in the Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Dancing Men”) he’d illustrated the process of removing coal from the coal face: which miner shovels out, which direction the coal belt moves. And then I stood in front of one of three surviving copies of Tyndale’s New Testament in English, a battered, hand-sized book open to Matthew 7: “Care not therfore for the daye foloynge. For the daye foloynge fhall care ffor yt fylfe. Eche dayes trouble ys fufficient for the fame filfe day.” From teaching at a Lutheran school – and from Hilary Mantel’s novels – I had reason to know how long it takes a human body to burn, how rightous the motivations of those who light the torch. Tyndale burned for words on a page that need no translation to the literate sixteenth-century English layperson, or to me.

After a long time, I went back downstairs to the café to have lunch. Brushing through the crowded tables, I looked down and George Orwell looked back: a tall lanky man in his 70s, long lined face incongruously capped with dark thick hair, a little mustache, vaguely motheaten-looking sweater and trousers, a certain air of immovability. Can’t be him, I argued with myself, he’s dead! But the truth is, something in me only expected it. AA Gill writes that “If New York is a wise guy, Paris a coquette, Rome a gigolo and Berlin a wicked uncle, then London is an old lady who mutters and has the second sight. She is slightly deaf, and doesn’t suffer fools gladly.” But if you come to her with a real desire to see the layers of stories built up in her collective life – on her terms – she will show them to you. Maybe.

Growing up in the South prepares you for historical travel anywhere, teasing stories from the scraped and rewritten palimpsest of the troubling past. And there are troubles here, and everywhere. I was on this trip, after all, to trail along in the footsteps of young writers who cheated on their wives and ran away with other girls and died of tuberculosis at the height of their powers and remained haunted, all their lives, by the ghosts of mothers they believed they’d killed. They were not always happy people, not always treating other people well. To his menagerie – monkeys, lions, leopards – at the Tower of London, James I charged the “admission” price of a live cat or dog, for their food. (A 17c newspaper breathlessly describes how a Tower menagerie keeper extracted himself from a python’s grip.)

Fresh from teaching 1984 and Eichmann in Jerusalem this spring, I felt more than ever the Tower’s reinforcement of state identity and might, closer to Orwell’s Oceania than the merrie-olde-England of London 2012 cliché. Motoring up the Thames to the Traitor’s Gate, you thank God you are not young Elizabeth I being brought under that dripping arch, wondering if she’ll ever come out. You can still go to the spot where Anne Boleyn was executed, although the wooden block I last saw there in 2000 has been replaced by what has to be the most sentimental excresence in the history of public monuments. (Who gives the past its dignity, and who reads it as a source for wincingly naff “princess” imagery in the years of William and Kate, is a good sorting device in a city like this.)

But the voice I heard most – here and all through this trip – was the voice of John Keats. The flowers in the garden of the Hampstead house he shared with his friend Charles Browne – and with the Brawnes – were all in summer bloom, humming. To set budding more/ And still more, later flowers for the bees/ Until they think warm days will never cease….

It wasn’t until we got out of England that I began to hear Byron’s voice, too. An afternoon of hiking up the side of a hill in Geneva, among what has to be right up there in Europe’s Top Five Most Expensive Neighborhoods, did eventually yield the Villa Diodati – and a little herd of Brown Swiss cattle browsing in the meadow underneath the villa. Like everyone, I stood and craned my neck to see the second-floor balcony and windows and loggia through the fence, imagining Byron and Polidori and the Shelleys with their feet propped on the railing, enjoying the wind from the lake. You can’t get into the house, which is in private hands, but you can wander past the gate and sit in a beautiful little park with an informational marker right next to the house. When we finally trudged up to the park, a group of teenagers was sitting in their car, smoking, and what looked like a man and his son were deep in conversation on the bench. The teenagers melted away, and the man and his son nodded at us and got in their car to drive away. From out of nowhere a delivery van came swooping around the curve and nearly hit the car: among what had to be the fifty French variations on “muthaf&cka” that followed, I heard Byron laughing.

By reputation and cliché – but also in fact – Venice is a deeply Byronic city, weary from the long adventures that still color its present days, teasing out the sensory pleasures that are and aren’t a sufficient route to the ineffable things you can still feel this city seeking, in its heart: beauty, wonder, permanence that water and time seem to make more impossible every day. From the air, you spot the incongruous clot of brown rooftops floating in blue waves and think, “it’s so SMALL!” But once you enter the Grand Canal, you are inside something that feels as alive as a heart or a brain, surrounded by walls and windows on every side, and it feels strangely easy to forget that all that open ocean is there. Of course there are umpteen billion tourists in the summer taking pictures of every damn thing: they could limit the number of visitors per year to save this place, but then its major industry would be gone. From about 120,000 in 1980, the population of Venice has declined to about 60,000 in 2009. What’s keeping this city alive is killing it, and the other way around. Fake carnival masks, knockoff Gucci, grinning people in gondolas taking each other’s pictures. And yet.

Byron was as avid a Venetian partier as anyone, swimming home drunk along the Grand Canal and pushing a candle on a little raft in front of him. But his presence – at its best, with the strength, commitment, and inquisitiveness of someone who had more common sense than his party-boy reputation suggests – is felt most strongly on the little island of San Lazzaro, a short water-taxi ride outside the city, which is still home to the Armenian monastery Byron visited to take language lessons and talk with the monks about the cause of Armenian independence, which he supported (still a live issue in the twentieth century). The whole island is maybe not quite the size of a good city block. But its small garden and vineyard thrive, its young olive trees rustle in the wind, its cicadas drone in the big pine trees. You think of Yeats’ Innisfree, and you know that Byron found his own measure of peace here too.

Wandering away from the beaten tourist tracks around San Marco, Mama and I got caught in a sudden powerful rain that whitened the sky and flooded the cobblestones. Through the downpour we heard singing, drumming, and chanting. A group of Hare Krishnas – young and beaming as my students – lined a narrow lane of shops, and although some people scurried past, head down and scowling, the man who passed in front of us paused, grinned, and danced down the passage through the rain, to applause from the Krishnas. So we did too. On the other side we took shelter under a giant tree, loaded with almost-ripe green figs. In Alabama our fig trees grew against the barn or the toolshed or the old tin-roofed well house at Oak Bowery, made from rough cedar posts. Who knows what that tree is rooted in. But something below and above and around the tourist tackiness does sustain this city. In a distant alley, a window full of plaster mask forms – cat, clown, flamingo – and a clutter of tools just visible inside announced an artisan, not just a souvenir shop, who’d been there a long time. Incense and singing came through the open door of an Orthodox church: at the far side of the altar, a small group of shawled women surrounded a priest, bowing and straightening to cross themselves at the feet, hands, head. One of them caught my eye: a curious, open, rapt inward gaze. Ashamed of watching, we moved on.

Like everyone, I bought a Murano-glass pendant in Venice, swirls of red and gold. Packing to leave, I dropped it on the floor and broke the corner off. You come here to find me, something in this city murmurs, and that’s fine – if you can – but you won’t take me out of here.

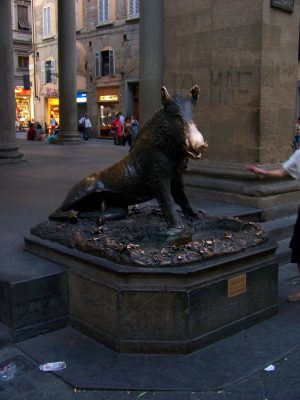

With only a day and a half in Florence, we didn’t go inside the Accademia or the Uffizi or the Duomo, saving those for my return with students – instead, we walked, learning the city. We rural Alabamiowans felt instantly, mysteriously comfortable there, despite the ubiquitous luxury shops (where do people in such a broke country get the money? You could ask the same question on Fifth Avenue, I guess.) In spite of everything, Florence still feels to me like a big old country town, presided over by a spirit that blends multiple practicalities rooted in the land and the body — farming, politics, art. Shelley wrote “Ode to the West Wind” here, but this city feels less ethereal than friendly and practical, with a strong sense of its own dignity. Come around the corner and you see a bronze statue of a wild boar, which troubles Tuscans as much as rural Alabamians and is honored in the same backhanded grudging admiration-at-its-cussedness way.

Stand on the Ponte Vecchio and the beauty of the sunset over the Arno just stops you, never intimitating but warming.

We walked down past the Brownings’ former house into a neighborhood beyond tourists’ reach: bursts of piano and opera from an art-gallery reception going on beyond an open door, women in high heels and motorcycle helmets buzzing home to their apartments above the street, a corner of a painted ceiling glimpsed upward through an open window, a shirtless young man turning to lift a canvas onto an easel, ripe fruits and powdery sausages in tumbled market-window displays, a friendly gray tabby cat rubbing against my fingers through the inside of a window screen, and purring. I took Elizabeth Spencer’s “The Light in the Piazza” to the Piazza della Signorina and read it there, to celebrate the many ways she has guided me, and still does. Even the massive Duomo feels kind of homely – sides patterned green and pink and white with native Tuscan marble, set right in the middle of the city streets, close enough to our hostel that we could gaze drowsily at it from our window as we fell asleep.

It’s interesting the moods that govern the way traces of the past linger in a place for you. Of course, according to Mary McCarthy – who I found in a Florence bookshop – the Florentines spent much of the medieval period pouring boiling pitch on each other out the windows of houses, in one endless feud of what seems like all against all. But something about Florence feels persistently local, realistic, and human in a way Rome does not. Florence is presided over by Dante, with his precise registers on human scales of joy and pain, rather than Caligula, Constantine, or Marcello Mastroianni. When he wants to render suicide in The Inferno, Dante renders souls as trees, who tear their own branches and leaves, in “pain and pain’s release,” simultaneously. There’s his house, down in a warren of streets, with the well – or an altar – within easy reach of the door. And the river a short walk away, always going past.

Of course, the Colosseum was the first thing we saw in Rome. I was woozy from a weird blood-sugar crash and generally tired. But looking at those pitted ruins, I could only see empire, its fuels and its byproducts – exploitation, entertainment-jadedness, military showoffiness, human and animal life. Flood this arena so we can fight in ships! Turn these humans, or animals, or humans and animals, loose to tear each other apart! Spritz the air with exotic perfumes so we can remind ourselves how many places we’ve conquered! And put up a giant arch to thank, for our victories over our enemies, the Christian God we chose from among the other faddish little cults out there! (I believe Robert Hughes’ account of Constantine’s “conversion” rather than the more optimistic ones.) But mostly, having just stood again by her statue in London, I could think only, “these were Boudicca’s enemies.” I was not impressed. You disgust me. You are everything this world was in your time and still is and should not be. Looking down into the Colosseum arena, I saw a giant open maw.

And yet. In St Peter’s Basilica, I passed one of the side chapels where a service was going on, named “penitence,” and felt an urge to go into that little booth and confess. I’m not Catholic, they wouldn’t let me, and if I went in and began to confess I’d never stop, and I wouldn’t stop crying. (How sharp your own shortcomings poke against your skin in the presence of a saint’s bones.) But this was only one edge of the feeling of doubleness I battled with all through Rome, whipsawed by the twin currents which run palpably together there: real beauty and power, side by side with the brutish power of might and money and state and state-church persecutions, entrenched over hundreds and hundreds of years. Even in Vatican Museum, crowded almost beyond capacity (guards in the Sistine Chapel repeatedly pleading with people to stop taking pictures and keep their voices down in this sacred place), I battled between wonder at the beauty of this art, the diligence of Michaelangelo on his scaffold (that dirty man who painted his own loose skin, shed like a coat, in a saint’s hand, and complained, “I’ve grown a goiter dwelling in this den”), my admiration of those muscular Sibyls (those women who labor at wisdom), and an unshakeable, gut-level disgust – the ghosts of Luther, Calvin, and Tyndale shaking their heads – at the power that brought and consolidated it there. Raphael’s kid with the notebook – my favorite part of “The School of Athens,” aside from Raphael’s bright eyes looking back at me – only partly helped. (His hair streams sideways just like William Blake’s Ancient of Days, or long weeds in an Iowa river.)

Tyndale’s remembered voice asked me Why feift thou a moote in thy brothers eye and percevest not the beame that ys yn thyne owne eye? But I could not stop judging Rome, and finding it wanting, despite a corresponding sense that I was the one getting something wrong. I saw my first Caravaggio, “The Deposition of Christ.” I went looking for this one but got lost – as close as I knew I was, it just kept receding. At the Trevi Fountain, the surging forms and cool water were unreachable through crowds of tourists (and pickpockets, a problem for us only in Rome.) People said Venice was the elusive city, but for me that was Rome, where – unlike Venice – I frequently felt lost and confused. Even angry. Late in the night a mosquito whined over my head in the hotel room, and I slapped my own face in the dark. William Shelley! Malaria!

This feeling didn’t ever really let up until I stood on my last afternoon in front of the graves of Keats and Severn and Shelley and that self-promoter Trelawney. Maybe this is the real reason Rome is so off-putting and sad: this was where John Keats came to die. It’s easy to let the real man – short, tough, feisty, moody, laughing, sensual – get lost in a hazy Young Poet cliché, a process that, as Stanley Plumly makes clear, began even before Keats’ death. In what is now the Keats-Shelley Museum, you go up narrow, rickety stairs that make you wonder how Severn ever got his rented piano up there. You examine a red swatch of Byron’s marriage-bed curtains, Trelawney’s dagger, an urn containing a fragment of Shelley’s jawbone, and wisps of all the poets’ hair: Byron’s dark, Shelley’s dark auburn, Keats’ a sandy light auburn. The room where he died is small and narrow, with a window out onto the clamor of the Spanish Steps and painted flowers on the ceiling. Severn sat up during Keats’ last hours, drawing him, to keep himself awake. If these windows were open now, the heat would draggle your hair across your forehead, drain you, as it does, as sweaty and weary as Keats’ face on that page.

Two elderly English volunteers greet you and talk with you at the Protestant Cemetery, sending you on your way toward the grave in the back corner, where of course you are not the only young woman with a notebook, and not the only friend who wants to apply just a few too many words trying to describe what John Keats means to you. Keats wanted only his famous epitaph: “here lies one whose name was writ in water.” Brown and Severn, out of love, couldn’t let it rest. Neither could the Victorian fan whose laborious acrostic beginning “Keats! –“ is spelled out in a plaque on the cemetery wall. You pick lavender, surreptitiously, and eventually move on up to Shelley’s grave – nearly tripping over little William’s stone, flat against the grass.

They say that Southerners are people who hold grudges. The older I get, and the deeper in captivity to my imaginings of the past, I find I hold grudges on behalf of the dead. Really, really well. Whether my interpretations are historically supportable or just imagination, I can’t always say. But I cannot deny the feeling of being taken aside and whispered to that comes over me at a place where layers of human life have been, as I walk over ground that – as Hilary Mantel writes about the English countryside – is “keeping warm the seeds” of war, memory, love. Any ghost wants only to be understood. Any writer wants only to listen, and get it down. I’m a different writer, a different teacher and person, for having been here. And when I go back with my students in January, it will all be different, yet again.

I need a “love” button for this–like just isn’t strong enough. Keeping thinking about this piece of wisdom and perfect metaphor: ” . . . so many experiences and feelings that keep pressing outward, gently, on the walls of the self, which is always threatening to collapse in on you like a badly rigged tent, confining you in a small, closed, stifling space that comes, if you aren’t careful, to seem like your natural home. Thank you for taking us with you on your trip, and what lucky students you have, in both your generosity to shepherd them on the trip in January but also in your generous spirit in sharing your struggles and joys.

thank you, thank you. of course, there’s more that can be best told to you over a glass of wine. 🙂 the real gift was being there with my mom. it was very special to share that with her.

Holy shit, Amy- I want to go with you in January!

i wish the college would give me money to bring (let’s call them) Amy’s Study-Abroad Trip Fellows. 🙂 you would be, shall we say, “invited to apply.” 🙂

amy, i loved going to these places with you! thanks for the quest! t

Amy, you made that real in the way it was meant to be experienced. Thank you.

thanks so much, y’all. i am really glad some of what i was feeling in these places came through! wish y’all could have been there too.