https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6fbahS7VSFs&hl=en_US&feature=player_embedded&version=3]

Young parents laugh nervously as they film their child, whom they have placed up against the glass of a lioness’s cage in a zoo. Behind the glass, the lioness is deadly serious: she scratches and bites the barrier separating her from one good bite of food. Incredibly, the father giggles, “Say hi, kitty, kitty.” The mom directs the baby, “Jack, look behind you.” A nervous female adolescent voice off camera, also giggling, volunteers, “That’s, like, almost…. not cool.”

Watching this make its way around the Internet lately reminds me of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” and the kitsch staging of babies as food – only in a society with the relationship to food ours has (abused, misunderstood, but still, we imagine, plentiful and forgiving – just like children themselves) could this be possible. It’s not funny for the lioness. It’s not funny to these people. To those laughing, it’s entertainment. And the only person even venturing to differ is that off-camera female voice, venturing on what might, just might, be edging toward a (gasp) judgment: “that’s, like, almost…. not cool!”

Of those who mutter “who am I to judge” when confronted with human evils like the Holocaust, Hannah Arendt remarked that when you say to yourself, ‘who am I to judge?’, “you are already lost.” There is criticism or insult, “don’t judge me.” And then there’s true judgment, the moral vision we need to recognize what kills human, or animal, dignity. In this lioness-baiting video, you see what the refusal of that judgment has done. The deeply serious business of animal selfhood and survival — that vivid, totally self-contained, violent and wild and foreign world — just becomes a joke. Like the pontoon-boat idiots in a million Florida vacation videos, filming a gator with their Iphones as it rises out of the water to take bait. Isn’t this the root of every moral political and social evil of our time? Let’s put the breathing, complex thing behind glass and look at it through a screen, suppressing as unhip our own entirely natural sense that maybe this whole entire way of doing things is fucked up. Maybe, just maybe, it is, like, on the verge of totally being not cool. By contrast, what happens when we let the world be itself – violent, real, complex – and submit ourselves to understand it, with the understanding that comes fundamentally from respect? Not from the desire to be entertained by, but to understand?

This spring at our college, two great and generous visiting writers have helped my students and I meditate on the process of submitting yourself to the dignity of that other real creature, that other real thing. First, Benjamin Percy, reading about a soldier’s memories of Iraq, stopped an audience’s breath with one ruthlessly specific detail after another: “The boy in a tattered robe hurling a rock at him and darting down an alley. The old woman who touched his face with her hands and spoke what sounded like an angry song. The camel shot with a flare as a joke, its hindquarters on fire, braying and galloping in circles, trying to outrun the burning.” When the reading was done we were harrowed and sober and moved. Two weeks later, Mark Oppenheimer described to students the level of community at his synagogue, and the unexpected meaning it bears: “we serve a lunch for everyone every Saturday,” he said, “and for some of our congregants, some of those very old people… it might be the only meal they get all day. It might be the only time all week they even see another person.” Then Mark took off his glasses and wiped his eyes. “Excuse me,” he said, and the students nodded. They had been learning from him so many of the qualities that make a great writer: wit, perseverance, thoughtfulness. Now they learned, as they had with Ben, one more: vulnerability.

The following day, in my Advanced Creative Writing class, we returned to our ongoing discussion of how to achieve that sort of fearlessness and tenderness as a writer. Here, I always think of the moment in Lorrie Moore’s “People Like That Are the Only People Here” where a mother who’s just learned her toddler has cancer rocks him to sleep: “If you go,” she keens low into his soapy neck, into the ranunculus coil of his ear, “we are going with you. We are nothing without you. Without you, we are a heap of rocks. We are gravel and mold. Without you, we are two stumps, with nothing any longer in our hearts. Wherever this takes you, we are following. We will be there. Don’t be scared. We are going, too. That is that.” I can’t even think of this – much less read it aloud – without tearing up. Because this is the moment where Moore’s semi-ironical half-self-hiding mask slips and you see pure, naked grief and love, mixed together in the way they so often really are. “No tears in the writer,” I wrote on the board, quoting Robert Frost, “no tears in the reader.”

Then we read aloud the results of an exercise I’d given them, straight out of the news: write this or a scene from this while avoiding every tempting cliche. The results were incredible, and unsentimental: The aunt. The nurse. The father. And in the last moments of class, one student told us about approaching her dead father’s coffin to touch his face. It burst out of her in a tone of utter honesty tinged with wonder. “I knew,” she said, “I knew this was not my dad.” The air in the room seemed to change temperature, and color. Something else was here with us. None of us had to remark on it because we all knew it was there. Some spirit of honesty, clarity, truth. We all leaned inward, and a little closer together.

We talked, too, about what writing looks like when the writer is not fully invested in embodying reality. Here’s one recent example, and a discussion of it, from Lev Grossman’s TIME Magazine review of Sadie Jones’s The Uninvited Guests:

“At this late date any English country house novel, however formally traditional, must be highly self-conscious if only by default, and like The Stranger’s Child, The Uninvited Guests is very aware of itself as a second-order fiction. Or if it isn’t, the reader is.

There is something slightly irreal and super-bright about Jones’s prose — it conveys a sense that her knowledge of the world she’s describing is also second-order, i.e. derived from books, or at least refracted through them, rather than observed first hand, unmediated. Describing the ladies on horseback, Jones writes: “Emerald had never ridden side-saddle but — most comfortably — astride, long before it was fashionable for modern young women to do so. Charlotte had been raised amid and among many occupations and worlds, one of them being horses, and she had an unconventional belief that the side-saddle was a ludicrous contraption, no good to woman or mount.” It’s not unconvincing, or implausible, but it is both very precise and slightly low on detail, so that the people and beasts in question feel not so much historical as animatronic, or very expensively CGIed. It’s not unpleasant, but it’s not realism either. There’s a whiff of fan fiction about The Uninvited Guests: one hears the echo — the echo of an echo, really — of Cordelia remarking in Brideshead, dismayed at the state of the local hunting protocol: “If only you knew how unsmart the Strickland-Venables are this year. They’ve even taken their grooms out of top hats!”

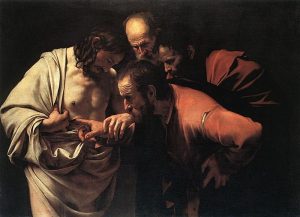

Readers can tell when the writer hasn’t touched — really touched — the world she’s writing of, and yes, it is possible to touch the worlds of historical fiction too (get on a horse, for instance, if you haven’t.) Be the kind of writer who presses toward physical experience whenever she can. In some translations of the New Testament story, I told them, “Doubting Thomas” is translated “Touching Thomas” for just this reason: he has to know, he has to be sure, and only the evidence of his senses will do. You honor the world and the mysteries it cloaks by touching and seeing it as it is, on its own terms, with the dignity of clear sight. Not through an iphone screen or through recording an event even as you are looking at it so you won’t forget. By looking at it and struggling — always forward, any amount — to see clearly and write down what you see. To communicate it.

That is what friends and community members did yesterday to take part in Bill McKibben’s 350.org “connect the dots” movement of worldwide demonstrations on May 5. We stood on the bank of our river, which had nearly overtopped its dikes and flooded the whole town in June 2008, and marked the high-water mark with our own hands, our own bodies and presence. Everyone in this picture was “underwater.”

Bear witness. Touch and understand. Make the world real in your own mind, and yourself responsible to it, as it is. Write, and write, and see.

This hurts just to read, in the best possible way.

thank you. thank you!