In one of his famously long, thinking-out-loud journal letters to his brother George and sister-in-law Georgiana, finished and sent in January 1819, John Keats talks about cats:

There is another thing I must mention of the momentous kind;– but I must mind my periods in it—Mrs. Dilke has two Cats – a Mother and a Daughter – now the Mother is a tabby and the daughter a black and white like the spotted child – Now it appears ominous to me for the doors of both houses are opened frequently – so that there is a complete thorough fare for both Cats (there being no board up to the contrary) they may one and several of them come into my room ad libitum.

A cat lover myself, I first read this through the blurry lens of ailurophilia, gliding right over the phrase “the spotted child:” the daughter cat has spots and she’s the child of the mother cat, right? But rereading Keats’ letters recently, that phrase leapt out at me, because I’d seen a “spotted child” in London a few months earlier – a human girl. And Keats might well have known such children too.

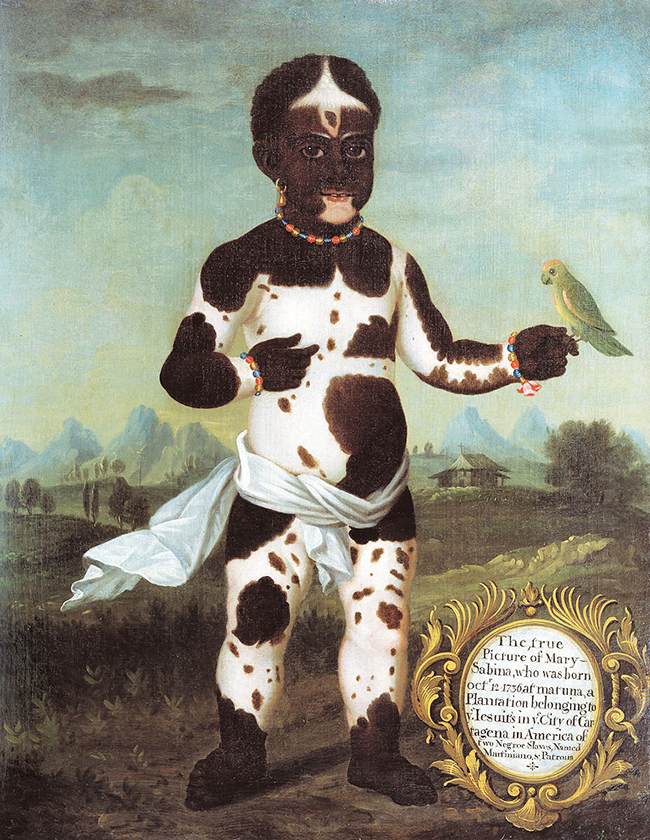

The child in question is Mary Sabina, whose unsigned portrait, painted sometime in the eighteenth century, hangs in the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London. The caption reads “The true Picture of Mary Sabina, who was born Oct 12 1736 at matuna, a Plantation belonging to ye Jesuits in ye City of Cartagena in America of two Negroe Slaves, Named Martiniano & Patrona.” Like numerous other “spotted” or “pony”-boys or –girls pictured as medical anomalies or sideshow curiosities throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, she had vitiligo, a disease which causes the skin to lose color in patches.

Mary came to the world’s attention when Jose Gumilla, a Jesuit priest “visiting the sick in the plantation hospital,” saw a woman “who had with her a six months old child of so extraordinary an appearance that he was convinced he would be accused of exaggeration in his description of it” and “advised the mother to guard the baby very carefully lest someone should cast the evil eye upon it” (Dobson 273). The priest thought that the presence of the mother’s black-and-white pet dog may have influenced the child’s coloring in utero, a similar reasoning to that offered by the twentieth-century vitiligo patient Frances “The Spotted Pony Girl” Lopez of Johnson City, Tennessee: “Physicians claim my condition is caused by my mother, being in a delicate condition, was frightened by a spotted pony.” According to the Hunterian’s website, “Mary Sabina does not appear to have been brought to Europe, but images of her were circulated widely – a kind of substitute exhibit.”

I’ve seen this portrait myself several times, since the Hunterian is my first stop on my study-abroad course “In Frankenstein’s Footsteps: The Keats-Shelley Circle in London, Geneva, and Italy.” Still welcoming visitors at the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, the Hunterian is based on the specimen collection of the pioneering surgeon John Hunter (1728-1793). And it’s a pretty good stand-in for Victor Frankenstein’s lab. As described in Wendy Moore’s excellent biography The Knife Man, Hunter was brilliant and relentless, so driven to discover and experiment that he infected himself with syphilis to study the progress of the disease and grafted a human tooth into a rooster’s comb to see whether it would take. (It did – you can still see it in the Hunterian, since, like all Hunter’s casts and preparations, it’s amazingly well-preserved.) I met Hunter years ago in Hilary Mantel’s brilliant novel The Giant, O’Brien, where I also met one of the Hunterian’s most famous residents, Charles Byrne, “the Irish Giant” (1761–1783). Imported to London and exhibited as a sideshow curiosity, Byrne drew Hunter’s attention for his unusual height, over seven and a half feet tall. Byrne realized he was in danger of becoming a specimen and begged his entourage to bury him at sea, so that his body could escape Hunter’s knives, yet after his death, bribes from Hunter ensured his place in the museum, where his skeleton hangs today. Standing in front of Byrne’s time-browned bones is a wonderful place to tell his story to my students and ask them to think about where scientific curiosity might lead us – as it led Victor Frankenstein. And just around the corner is the portrait of Mary Sabina, given to the museum in 1880.

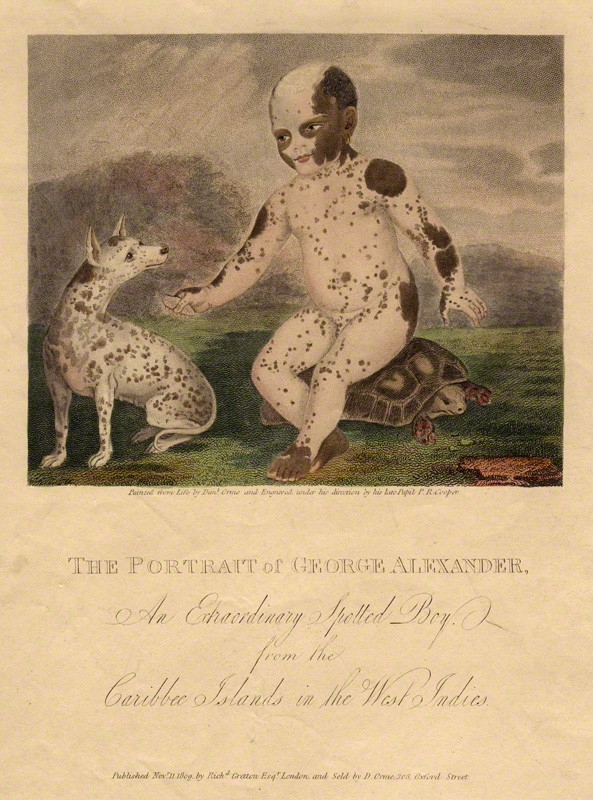

Yet Mary Sabina was not the only “spotted child” whose image might have been known to Keats. George Alexander Gratton, the “spotted boy” (1808-1813), was exhibited in London throughout “much of his short life…described as ‘the Beautiful Spotted Negro Boy’ and ‘a fanciful child of nature formed in her most playful mood.’” Like Mary Sabina, his image was also circulated widely. The showman John Richardson exhibited George to public and private audiences for a fee – sometimes, according to the Hunterian’s website, for “up to twelve hours a day.” Born on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent, George was somehow “transported to Bristol” and “delivered into the care” of Richardson – a squirm-inducing voyage at the tail end of legal slavery in the Empire. (Richardson, writes the historian Lucy Inglis, “had apparently paid a thousand guineas for George.” His parents’ feelings about the transaction are not recorded.) Yet Richardson seems to have treated George with genuine affection, and when George died of a tumor of the jaw, age 5, Richardson buried him in his own family plot in Marlow, leaving instructions for George’s headstone to be linked to his own.

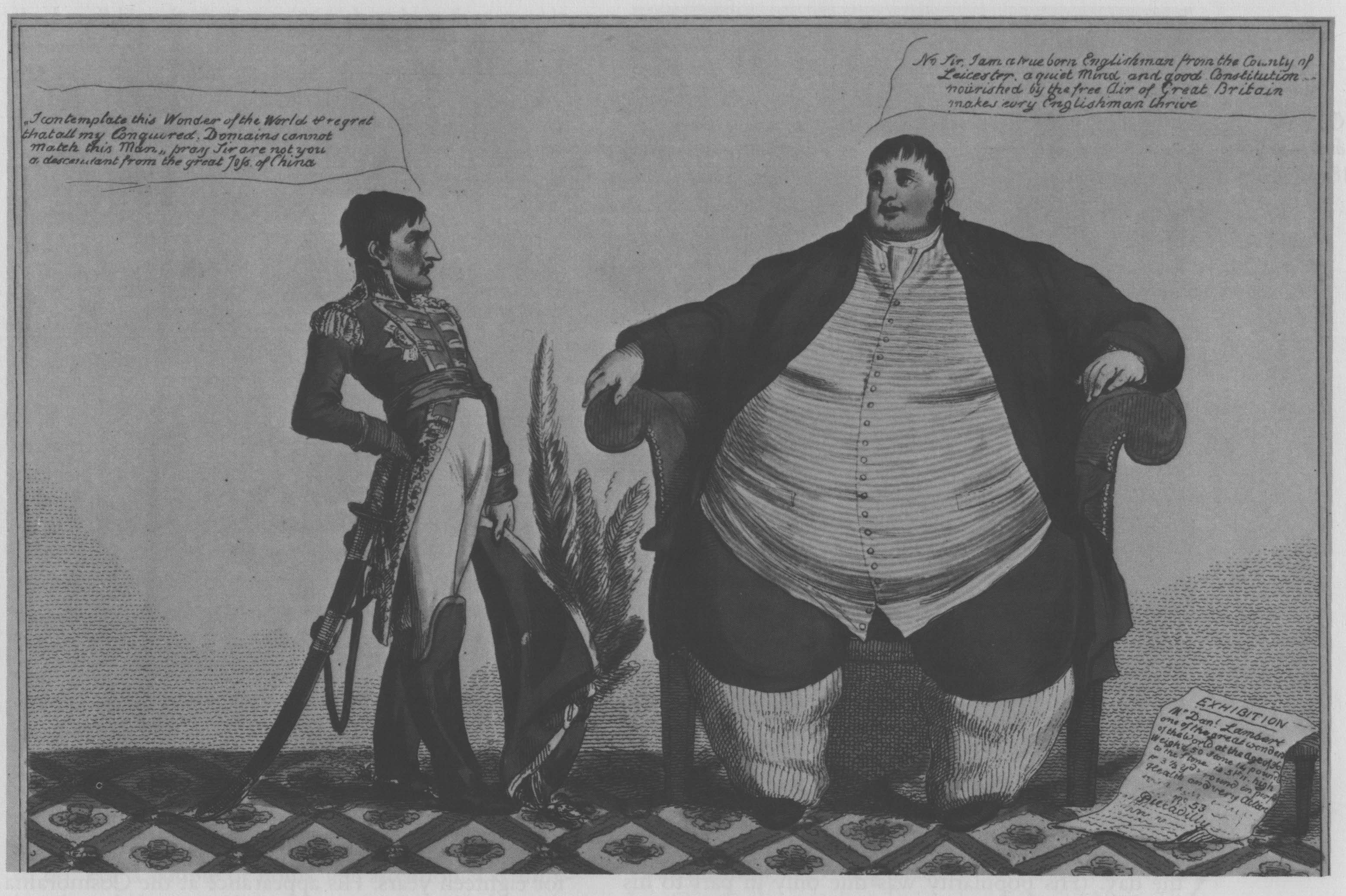

The lives of Mary Sabina and George Alexander are part of a story of medical anomaly in Georgian England that expands and frequently horrifies our own historical and cultural imaginations. Who can really know – really – how people of other times and places experienced their own bodies, the bodies of others, “difference,” “normalcy?” We must acknowledge the spirit and unknowable, private complexity of individuals even as individual cases make us pause: an infant taken from his parents, who were slaves, paid for with a thousand gold guineas as an investment that paid off. But little George was not unusual. Tiny Caroline Crachami, “the Sicilian Dwarf” (1815-1824), whose skeleton also resides in the Hunterian, was essentially stolen from her father, an itinerant Italian musician in Dublin, and brought south to London to be exhibited. (There are accounts of her crying and swatting away the hands of strangers as she stood upon a table.) We’ve seen how Charles Byrne was brought from Ireland to be exhibited, too. And “freaks” even had their political uses, as seen in two cartoons. Daniel Lambert (1770-1809), England’s fattest man, became a symbol for Britain’s health and strength during the Napoleonic Wars, as “Boney” marvels, “I contemplate this Wonder of the World and regret that all my Conquered Domains cannot match this Man,” while Lambert replies proudly that he is “nourished by the Free Air of Great Britain [which] makes every Englishman thrive.” (Wikipedia reports that Lambert was “highly respected for his expertise with dogs, horses, and fighting cocks;” at the time of his death, he weighed 739 pounds.)

People with goiters, neck pouches resulting from iodine deficiencies, were exhibited as “Monstrous Craws” in the city, leading caricaturist James Gillray to comment on the perceived greed of the Royal Family (with the Prince Regent looking slyly on, poised between his parents).

All this messy, fascinating medical anomaly – and the shadow of John Hunter, whose colleague, Astley Cooper, was still active at Guy’s Hospital – would certainly have been an active presence in Keats’ medical training and poetic imagination, given the omnipresence of “sideshows” in London and, in general, the greater susceptibility to accident, disease, and physical disfigurement in a world of hard physical labor and imperfect sanitation. The poet Dean Young wonderfully imagines this period of Keats’ life in “I See a Lily On Thy Brow” from his book Skid (2002):

It is 1816 and you gash your hand unloading

a crate of geese, but if you keep working

you’ll be able to buy a bucket of beer

with your potatoes. You’re probably 14 although

no one knows for sure and the whore you sometimes

sleep with could be your younger sister

and when your hand throbs to twice its size

turning the fingernails green, she knots

a poultice of mustard and turkey grease

but the next morning, you wake to a yellow

world and stumble through the London streets

until your head implodes like a suffocated

fire stuffing your nose with rancid smoke.

Somehow you’re removed to Guy’s Infirmary.

It’s Tuesday. The surgeon will demonstrate

on Wednesday and you’re the demonstration.

Five guzzles of brandy then they hoist you

into the theater, into the trapped drone

and humid scuffle, the throng of students

a single body staked with a thousand peering

bulbs and the doctor begins to saw. Of course

you’ll die in a week, suppurating on a camphor-

soaked sheet but now you scream and scream

plash in a red river, in a sulfuric steam

But above you, the assistant holding you down,

trying to fix you with sad, electric eyes

is John Keats.

This is my favorite way to do scholarship, and writing in general: read a lot, follow apparently strange interests, and see how they connect. (I learned much of this information about physical difference in Georgian England while researching my dissertation, for instance.) In this it resembles life, and imagination: fill your brain, look around, read a lot, and you can see at least some patterns emerge.

So overall, it’s impossible to say whether Keats actually saw a “spotted child” in person – but given the plenitude of likenesses of George Alexander Gratton, his contemporary, he would very likely have held the image of “the spotted child” in his brain, so seasoned and enriched with bodily imagery and knowledge as to appear in his poetry years later.

Wonderful and fascinating post. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks, Beth – I appreciate your taking the time to read!