Something about Christmas mixes emotion and memory like no other time. This is the hinge of the year, the liminal space where we could step one way or another way, where we can and can’t see what’s coming. Where we cannot avoid thinking about our relationship to time and how we perceive the world as it flows and unfolds around us, never stopping. Where we ask, with a mixture of trepidation and hope, what’s next?

A couple of weeks ago, I read this incredible essay. I shared it with students and got some of the most moving and thoughtful responses I’ve ever gotten from students on anything. Mortality, art, the heightening of emotion we get from coupling the two, the questions it raises on “how shall we then live” — not, apparently, the most optimistic thing to share with twenty-ish-year-olds, but questions they are eager to consider, and rightly so.

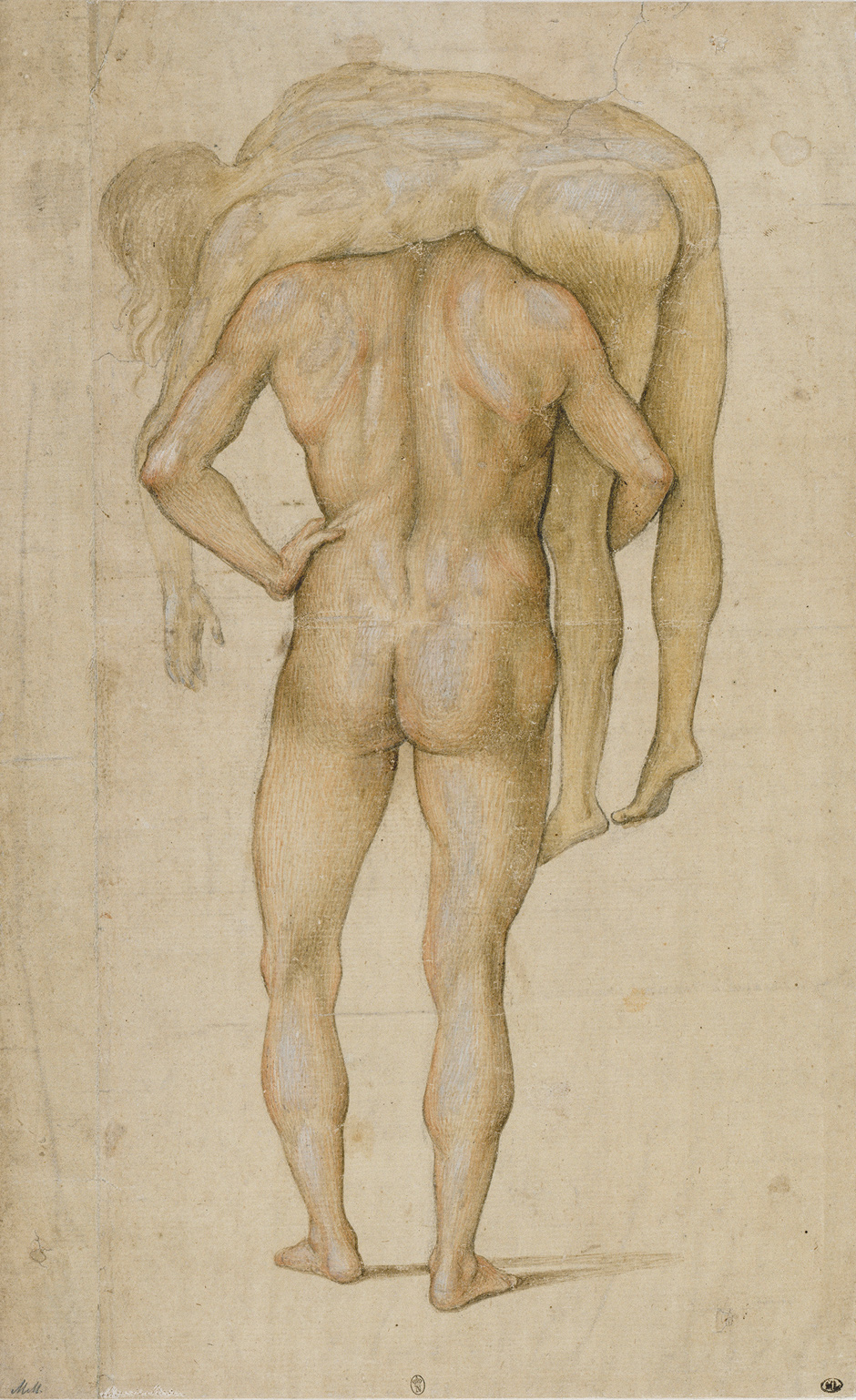

The centerpiece of the essay is this drawing by Italian Renaissance artist Luca Signorelli (c. 1445-1523), which prompts author Zadie Smith to sharp, compassionate, thoughtful meditations on art, life, and how we can live [that ancient human problem] fully and even joyfully in the presence of the knowledge of our own mortality. She writes:

“How to be more present, more mindful? Of ourselves, of others? For others?

You need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away, is the ability to just sit there…. That’s being a person…. Because underneath everything in your life there is that thing, that empty—forever empty.

That’s the comedian Louis C.K., practicing his comedy-cum-art-cum-philosophy, reminding us that we’ll all one day become corpses. His aim, in that skit, was to rid us of our smart phones, or at least get us to use the damn things a little less (“You never feel completely sad or completely happy, you just feel kinda satisfied with your products, and then you die”), and it went viral, and many people smiled sadly at it and thought how correct it was and how everybody (except them) should really maybe switch off their smart phones, and spend more time with live people offline because everybody (except them) was really going to die one day, and be dead forever, and shouldn’t a person live—truly live, a real life—while they’re alive?”

To those thinking, “Wow, this is depressing!” I’ll say, well, yeah. But admitting it is the start of spiritual practice, and adulthood, and real life while we are here, and it keeps us from using and exploiting others to prop up illusions about ourselves; we are responsible for living the most just and responsible lives we can, while we’re here. Pema Chodron: “Since death is certain and the time of death is uncertain, what’s the most important thing?” Marcus Aurelius: “Every moment think steadily…to do what you have in hand with perfect and simple dignity and feeling of affection and freedom and justice; and to give yourself relief from all other thoughts. And you will give yourself relief, if you do every act of your life as if it were the last, laying aside all carelessness, passionate aversion from the commands of reason, hypocrisy, self-love, and discontent with the portion that has been given to you.” Jesus, paraphrased: “This world is not all there is. But, even so, remember, while you’re here, that you are not the center of it. Act accordingly.”

But how we can keep being most alive? How we can keep seeing our lives and our surroundings and our opportunities for contact with others as eternally fresh and new, not dulled by habit? A few years ago at a writers’ conference, I learned from the writer Anthony Doerr (whose recent piece quoting him is here) about the Russian formalist Victor Shklovsky. “If we start to examine the general laws of perception,” Shklovsky writes, “we see that as perception becomes habitual, it becomes automatic….If one remembers the sensations of holding a pen or of speaking in a foreign language for the first time and compares that with his feeling at performing the action for the ten thousandth time, he will agree with us.” Doerr goes on:

“But art, Shklovsky says, ought to help us recover the sensations of life, ought to revivify our understanding of things—clothes, war, marriage—that habit has made familiar. Art exists, he argues, “to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known.” Sometimes you have to make yourself a stranger to your own life in order to recognize the things you take for granted. Like sunsets, or hot showers, or alphabets. My health, my family, the streams of photons sent from our star—how had I stopped actually seeing these things?”

Looking at Signorelli’s muscular man – so determined, so strong, so apparently eternally alive – carrying the corpse away to some destination we can’t see, I thought of Shklovsky again. Art had made me re-see my living body’s presence in this world. Who was Luca Signorelli, anyway? Having been teaching Dante and Michelangelo, my head was already full of the Renaissance. But Signorelli was new to me.

What I’ve been learning about Signorelli is not much, yet, but seems to suggest one thing: a good craftsman, kind of quietly overshadowed, then and now (perhaps inevitably) by Michelangelo and Raphael. In his Lives of the Artists (first published 1549-50), Michelangelo’s disciple Giorgio Vasari gives 75 pages to his master (whom he calls, basically, a spirit sent from God to make Florence, “the most worthy among all the other cities,” even more perfect than it already is) while giving Signorelli only five and a half. The beginning of the chapter is a little mixed: “Luca Signorelli, an excellent painter about whom, following chronological order, we must now speak, was more famous in his day, and his works were held in higher esteem, than any other previous artist no matter the period, because in the pictures he painted, he demonstrated how to execute nude figures and how, although only with skill and great difficulty, they could be made to seem alive.” Most of his account of Signorelli is a list of what Luca painted and where. “[D]uring his last years [in Cortona],” Vasari writes, “he worked more for pleasure than for any other reason like a man who, accustomed to toil, is unable or unwilling to remain idle.” Yet there’s also a charming anecdote about when Signorelli was a guest in Vasari’s own home and told the then-eight-year old Giorgio, who was obsessed with drawing figures instead of doing his other homework, “Learn, little cousin, learn.” (It’s kind of the Renaissance equivalent of the moment in John Lee Hooker when “Papa told Mama, let that boy boogie-woogie… it’s in him and it’s got to come out.”)

Yet Vasari also tells us, “It is said that when his much beloved son, who was extremely handsome in face and figure, was killed in Cortona, even as he grieved, Luca had the body stripped, and with the greatest constancy of heart, without crying or shedding a tear, he drew his portrait so that he could always see whenever he desired, through the work of his own hands, what Nature had given him and inimical Fortune had taken away.” This is a sterner thing, a challenge. In Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard (1973) – a classic nonfiction account of a part-spiritual-trek, part-naturalist-discovery-quest through Nepal, the real subject is not the elusive snow leopard of the title (glimpsed only once by Matthiessen’s scientist partner, never by the author himself) but what it means to confront reality without flinching, to immerse yourself in the present moment, to be in emotions without letting them bind or define you. As he writes, Matthiessen’s wife — a fellow author and student of Buddhism — has died of cancer. Yet he presses on, intent on the nature of this or any pilgrimage: a confrontation with reality as it exists beyond any illusions or emotions, difficult and radiant. “The sun is roaring,” he writes, “it fills to bursting each crystal of snow. I flush with feeling, moved beyond my comprehension, and once again, the warm tears freeze upon my face. These rocks and mountains, all this matter, the snow itself, the air — the earth is ringing. All is moving, full of power, full of light.” There is a dignity and a nobility in using one’s humanity to see both that humanity itself and the larger reality of which it is only one part. There is a dignity in that.

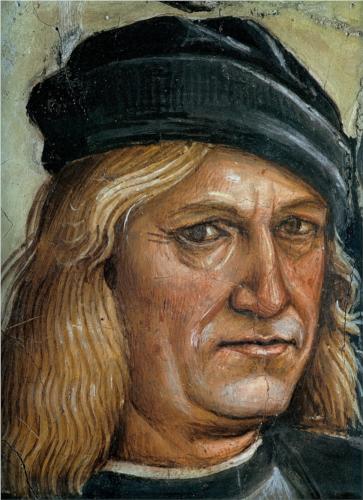

A closer look at Signorelli’s work reveals a kind of quiet, close-grained dignity and focus that refreshes our sight just by looking. Consider the self-portrait above – one of those little self-portraits Italian Renaissance artists were always sneaking into larger works. The man looks right at us and leaps off the screen. He’s as testy, reserved, yet forthright as any similar man we might know. He’s a human, looking at us across more than 500 years. The brushstrokes are not “refined.” This is not an artist as famous as many of his contemporaries. But he is a painter who knows how to do a job right, and does it so that it lasts. He’s a technician, a craftsman, taking pride in his work, as craftsman do, and thereby ensuring its afterlife. He doesn’t insist didactically on what his work should “mean:” in his clear quiet faces, in the muscularity or limpness of bodies, he just shows us what is. Look at Gabriel, below, with his tender throat, his unreadable expression. This is a divine being cloaked, for the painter’s purposes as for the poet’s (remember Milton describing in Paradise Lost how hungry Raphael gets, and how he eats?), in human flesh. Which, spiritually, is kind of the point.

Take a walk to the river on a bonechilling winter afternoon and you see a Signorelli-ish austerity to the world. The quality of the light, the starkness of the winter landscape, the small details that flash up: the white silt of snow among the roots of what’s still showing as golden-brown grass, seedpods rattling in the wind, river water slaty-cold and dark over the rocks. There’s a quiet dignity in the cold and starkness of the oncoming winter, a reality that braces and restores and teaches us to see again in this moment as it is. It’s important anytime: important now, at the hinge of the year, when something new can come. Jesus came in just such an ordinary way, born to a tired and bone-chilled girl sliding off her donkey to rest in the only place left: It’s okay, I’ve always imagined her saying to Joseph, we can stay here. I know you tried. And Jesus’s birth in a human form in a barn — not some elegant palace — was not just an accident. It renovates our vision of the divine in this ordinary world and in our own bodies, the bodies that sneeze and weep and shove their reddened hands into their pockets, squinting into the sun, determined to stay out and enjoy the severe and radiant light just as long as they can.