This morning, I took my first-ever pottery class, in the spacious studio in our college’s arts center, with a generous colleague, George, and a large group of students, several of whom had been in my classes before. I’m here on sabbatical, I said, to learn, just like you are. And the relief of being among them in the posture of a fellow apprentice was deep, even though, by the end of the two-hour session, that feeling had twisted around and taken several paths I did not expect.

As a writer and writing teacher (and yoga student), I thought I’d internalized the realities of doing and making: don’t expect perfection the first time (or maybe ever), don’t overthink, concentrate and let the material take shape in front of you, going back and back to smooth or bend or trim it. Use your hands, your body, your senses to learn and listen and adjust. Real and valuable change takes place over time, sometimes a lot of time. But it is easier to hold these ideas when you are not also learning something totally new – the time of excitement and discovery is also a time when fear can let a few old bad habits slip through the door.

“The bowl is a beautiful shape,” said George, “the inside and the outside are both totally exposed.” He taught us about clay – how more is always being created, geologically, how its tiny crystals lock together like wet magazine pages or decks of cards, how with working and reshaping, it releases the solar energy it has stored over eons literally right into our hands. Ooh, metaphor, I thought, I know what to do with that! I remembered how long I’d wanted to try this craft, how pleased I was when a dear graduating senior gifted me with a beautiful coffee mug she’d made in this same class. But as I worked at pinching lumps of clay into small figures and a small bowl shape, I realized also how exposed I felt as a student rather than a professor, despite my eagerness and happiness to be there, and how in response to that a smarmy professor-pleaser I have not been for years was starting to creep back into my head. I congratulated myself on accepting the fingermarks along the bottom of my bowl, smoothed and smoothed the breast of my little bird figure, hoping unconsciously for the instructor to pause at my workspace and praise me – saying this is good! or this is the best! Every student looks for that, waits for that, hopes for that. Every person does. And as professors, we need to ask: how much of our teaching would be so very different if we felt — really felt — how deeply the posture of the learner can be different from that of the teacher, and how easy it is for us to separate ourselves from “learners,” artificially, behind our wall of “expert” self-identification? What would be different if we put ourselves in the place our students are, every day, especially our students who are making art, with all the risk and confusion and unknown paths ahead we ourselves think we already know how to handle? What would be different if we really remembered how clueless our students can feel before the blank page or the silent keyboard or the familiar set of equations — a cluelessness buried, sometimes, too far back in our own experience to remember with that same keen sympathy?

Watching George at the wheel, so matter-of-fact and quietly skilled, centering a lump of clay and letting it spin up between his hands into a bowl, then a vase, I felt a surge of confidence: surely I would be able to figure that out. It looks so easy when he does it! Routinely I cook, plant, knit, judge jam textures and tomato ripeness by touch, eyeball the correct placement of pictures on a wall or the contours of a new garden bed, trust my body and its spatial abilities. Surely I could do this too.

So I sat behind the wheel and lowered my foot on the pedal. When I felt for the first time the lump of clay spinning under my cupped hands, I felt elated, totally focused, connected to every cell in the surface of the skin that was sensing this round motion and mass. “You centered that clay really quickly!” George praised. “Good! You seem to have a really good sense for that.” Then I dropped my thumbs into the middle of the mass to begin hollowing it out. And at some point, assailed by multiple simultaneous competing needs – depress the center, bring my left hand up and fingers down against the right hand to smooth out and deepen the inside of the bowl, fetch more water, ease up where the wheel friction is heating the side of my hand, depress the pedal (which works just like a car accelerator) – I lost the process completely, slewing a slather of clay all over the wheel surface. “Maybe ease up on the pedal,” George offered. (Familiar advice, unfortunately….) So I scraped it together and tried again, and again. Something about this form felt different, the center deeper from the beginning, the shape a little more under control. I let the wheel slow down. Watching carefully, George helped me shave an uneven place off the rim which was threatening to collapse the bowl, the only time he had intervened in the process. “Stop right there!” he exclaimed. “That is actually a nice piece.”

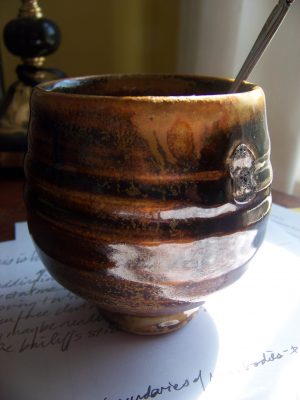

Just as my students have done with their written work, when they were in my place and I was in George’s, I blurted, “Really?” And I looked at it again. It was a nice piece. It is. A chunky little bowl with deep swirling fingermarks up the inside, somewhere between a vase and oversized handleless coffee mug in shape, with an accidental, insouciant lip in the rim. It has attitude. The outside is a little rough, mostly smooth. You can see the fingertip-wide rings of throwing lines there too, tell how this was shaped – inside and out – by touch. Obviously a beginner piece. But it also – even if only to my eyes – looks like the form this ball of clay wanted to take, the piece it wanted to be. Looking at it, I recognized my teacher was right. “Picture a river rushing up against a fallen log,” writes yoga teacher Michael Stone, “a new form comes about when the natural world pushes a form forward.” Stone is talking about the ongoing reality of being, the life that flows on and within and around us, and perhaps about pottery too. And writing. And any other art worth doing.

So I sliced my bowl off the wheel and put it on a board on “my shelf” to be fired at the end of the semester. What glaze? Red. Deep red. Maybe with some brown. But mostly red. By the end of the semester, I’ll have made more bowls and vases and other things to fill that shelf and be glazed and fired, but I’ll always remember: this bowl was first.

Wandering around the studio, I spotted a ceramic Buddha head perched above the kiln door and remembered suddenly the statue of Prajnaparamita I saw earlier this summer at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The smile on her face is deep and intangible and captivating. How on earth, you wonder, could anyone ever be so skilled as to capture that in stone? Yet somebody was. And you think suddenly and with total freshness about all the made, crafted, beloved objects you have ever stared at in museums or held in your hand or sipped your coffee from — Somebody made this. Who? Things look different once you ask that question. In a lot of ways.

Students have responded powerfully in my classes to these questions and to texts like Matthew Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft, sharing stories of carving spoons, husking corn, playing guitar, knitting sweaters, building boats, and experiencing the type of rapt absorption in reality that things with glowing screens can make impossible. Once you have tried making a physical material into an object that did not exist before, you see the whole tangible world, and the whole process of making, completely differently. They become at once fascinatingly strange and familiar. And you understand the way language, as the author Jay Griffiths has written, must be hooked to the physical world to keep its full range of motion and meaning. “The virtual world, the antinatural world, kills metaphor,” she says in her essay “Artifice vs. Pastoral.” “I couldn’t call language ‘shimmering’ without knowledge of the natural world, light on water.” And having had my hands in raw clay, brought for the first time against its full strength and fragility, I remembered the simile that strikes me every time I hear Handel’s “Messiah,” as the music rises with apocalyptic tension: “thou shalt dash them in pieces, like a potter’s vessel.” The fragile body, broken. Its inner space exposed. For the vase, the vessel, the body does have such a inner space, a sacred life. You feel the aptness of the simile, and its fierceness, and you wrestle with it because of its ordinariness. That humble container in which we live.

The coffee on my desk steams away inside a little footed cup made by some friends and favorite local potters, and looking at it now I see the subtle curlicue where fingers shaped the bottom, the even ribbing of finger pressure along the sides, and I know in my own fingers just how those marks got there. I feel a human presence that, in this era of soulless mass production and alienation of people from labor and labor from value, is profoundly reassuring — and necessary. When you try to make things, with your own hands, focusing only on that task and letting everything else fall away, you join up with that great, silent stream of human dignity and craft throughout time — of who we are, at our best — running constantly just below the surface of the visible world, palpable if you know how to feel it.

It is nice to know that professors can still experience what it is like to be a student again. Thank you for this. It was beautifully written, as always.

Loved this, and was surprised to learn about this new passion (to add to you amazing list of skills and talents) but here’s what was no surprise–the fact that the key skill of throwing pots, aka “centering” comes naturally to you. It’s so clear that even your body knows how focused and clear you are. So awesome. It’s an addictive thing, pottery, I know you will love your journey with it!