Advanced Fiction A Writer's Guide and Anthology

“This is an excellent text for anyone – college students, aspiring writers, or even the published working writer – interested in honing and developing fiction writing skills.” – John Fulton, MFA Program Director at The University of Massachusetts-Boston and author of The Flounder

Now available for pre-orders and exam copy requests!

A wise and practical guide to the writing and reading life for advanced undergraduates (and others) in the twenty-first century, Advanced Fiction (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023) includes several innovative features:

- Student Craft Studios: excerpts from students’ work, with their own reflections on the writing process

- Craft Studios, with close-up studies of selected stories reprinted in full

- Anthology stories including a range of places, cultures, languages, and embodiments

- And real talk about students’ real questions:

- How can I write about characters of different identities than me?

- What if friends or family recognize themselves in my work?

- How can I build a writing practice when I’m so busy?

- How can I make the move from writing short stories to novels?

- How can I engage readers in a fictional reality beyond the here and now (history, dystopia, fantasy?)

- How can I write about real life – the Internet, climate, politics?

- When I finish my writing class, what comes next – professionally and personally?

Table of Contents:

Chapter One: What Makes Advanced Fiction Writing “Advanced?”

Student Craft Studio: Shannon Baker, “Habits”

Craft Studio: James Joyce, “Araby” (1914)

Exercises

Chapter Two: Getting It Down: Writerly Self-Organizing, From Mind to Page

Exercises

Chapter Three: Mystery, Conviction, Form, and Risk

Student Craft Studio: Levi Bird, “On Stable Ground”

Craft Studio: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892)

Exercises

Chapter Four: Writing in Color: Culture, Identity, and Art

Student Craft Studio: Ian Wreisner, “The New Chicago”

Craft Studio: Rebecca Makkai, from The Great Believers (2018)

Exercises

Chapter Five: Invisible Engines: Purpose, Psychic Distance, and Point of View

Student Craft Studio: Andrew Tiede, “Till Death”

Craft Studio: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “The American Embassy” (2003)

Exercises

Chapter Six: Building a World – For Your Readers and Yourself

Student Craft Studio: Joel Murillo, “Cracker Jack”

Kari Myers, “Fields of Ash”

Craft Studio: Angela Carter, “The Tiger’s Bride” (1979)

Exercises

Chapter Seven: Trust the Process: Revising, Editing, and Writing At Length

Teacher Craft Studio: Amy Weldon, “The Serpent” (2018)

Exercises

Chapter Eight: Creative Writing and Your Future (Excerpt below!)

Student Career Studio: Andrew Chan, Derek Lin, Reed Johnson, MD, and Annika Dome

MFA Studio: Keith Lesmeister, “East of Ely”

Dr Weldon’s Fiction Prescriptions

Further Reading

Contributor Bios

Bibliography

Index

ANTHOLOGY includes….

Louis Jensen, Square Stories (translated from Danish by Lise Kildegaard)

Sofia Samatar and Del Samatar, “The Early Ones”

Aimee Bender, “The woman was born with snakes for hair” (previously unpublished in book form)

Namwali Serpell, “Account”

Kevin Brockmeier, “The Sandbox Initiative”

Cynan Jones, “Sound”

Nuala O’Connor, “Menagerie”

Tommy Orange, from There There

Jennine Capó Crucet, “How to Leave Hialeah”

Jane McClure, “The Green Heart”

Ron A. Austin, “Muscled Clean Out the Dirt”

Rick Bass, “Fish Story”

From Advanced Fiction:

From CHAPTER EIGHT: Creative Writing and Your Future

“Hope is invented every day.” – James Baldwin

Congratulations – you’ve made it almost to the end of this book and, probably, all the way through at least one advanced creative writing class. So what’s next? In this chapter, I’ll offer some advice that can help you move ahead, even if your dream career doesn’t have “writer” in its name. Our world’s changing faster than I can type, so I’ll try to be both specific and general enough to be useful. Mostly, I’ll focus on the actions you can use to propel yourself forward, whether you’re seeking an agent and publication or looking to land your first job in any field.

Thinking About The Future: Build Your Foundations

On November 3, 2020, students and I – understandably – had some trouble focusing. Not only were we sitting six feet apart, wearing COVID masks, but we were also waiting for the results of (ahem) a very important presidential election. So that day, we tried to feel at least a little less panicked and powerless by controlling what we could, right now. Together, we wrote about the following quote and questions:

If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them. Henry David Thoreau, from Walden: or, Life in the Woods (1854)

What is my “castle” – something I dream of doing or being?

What are three capacities I will need to have / show / demonstrate to be competitive for this – now or in the future?

What are three concrete things I can do in the next three weeks to take steps toward my castle’s door?

If I needed someone to write me a positive, specific reference to get into my castle, a) who might I reach out to, and b) when will I schedule a conversation with that person to talk about what that reference might look like and how I might position myself for it?

“A year from now, what will I wish I had done now?”

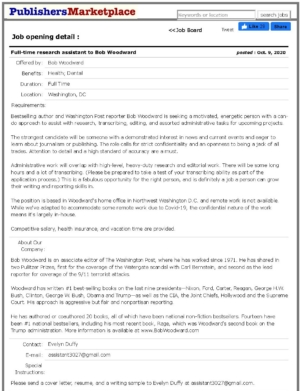

After writing and talking through some of our answers (which students said did make them feel better – although not as good as that election’s results!), we looked at an actual job ad:

If you have a “castle” like this job in mind, how might you move forward?

- Build capacities, relationships, and awareness of the world – these give you freedom to move.

What capacities would you need to show if you were applying to be Bob Woodward’s assistant? Curiosity, writing ability, independence and initiative, tenacity, ability to seek out good information from a variety of sources, and – hovering around the very name Bob Woodward – an ability to join in the major political and cultural conversations of the last fifty years. What concrete steps could you take right now? Start a habit of reading The New York Times and/or the Washington Post (Woodward’s own famous paper) – maybe your school, like ours, has free subscription options through its library. Identify an opportunity on campus related to this (see below). Check out one of Bob Woodward’s own books, look at his website, and watch the 1976 film “All the President’s Men,” starring Robert Redford as Woodward and Dustin Hoffman as his reporting partner Carl Bernstein. Each one of these things could be done within a week and would move you concretely toward your goal.

Think about your relationship with your writing community, and who might testify to your qualities as a reliable member of that community in professional references. Colleagues and I need people who write tenure letters or vouch for us when we reach out to editors and agents. Students need people who can write recommendation letters. And good recommendations start in good relationships (including that dreaded word, networking). Therefore, many professors, including me, will decline to write references unless we can write positive, specific ones.

Sounds harsh, but that rule goes for everyone. When writer and editor Rob Spillman visited my class in person, after several years of Skyping with us about his journal Tin House, students asked him for advice. Surprisingly, he turned to me, with a smile. “Be a nice person,” he said. “When Amy asked me to come here, I was glad, because I know she’s a nice person. The writing world is really small, and if you’re an asshole, people will find out.” I also like critic Hilton Als’s response, when asked if he was “ambitious:” “[A]mbition was what I equated with people who would use others to get what they wanted, or who stepped over the dead body without a second thought, once they got what they wanted. I don’t mind the word anymore, but the word to describe me is determined—determined to get better as a man and a writer. A determined person doesn’t court favor, discount, or hurt other people to get what they want, whatever that want is.”[1]

Let me tell you a story about that mysterious thing, networking: if you put yourself out there politely, people will usually be willing to help. Once, at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference (AWP), I was visiting the book-fair table for Graywolf Press. As a reviewer for Orion Magazine, I introduced myself to the publicity director so that I could ask her for an ARC (advance reviewer’s copy) of Paul Kingsnorth’s Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist, which Graywolf was about to publish.[2] A young woman next to me edged politely into my field of vision, said hello, and introduced herself as a student in an MFA program. Her voice was shaking – obviously, she was nervous – but she was still moving ahead, politely, and that was fine with me. “I hope this isn’t presumptuous,” she said, “but I heard you say you wrote reviews for Orion. If you don’t mind, can you tell me how you got started with that?” Better yet, I said, I’ll take you to meet them. We talked for a moment, and I gave her my business card. Then I walked her over to the Orion book-fair booth, where all the editors were sitting, and introduced her to them. We legacy-media GenXers have our flaws, but we know how lucky we are to have gotten into this world, and we like to help other people get here too. It starts with Rob Spillman’s advice – be a good person, and be sincere. And if you follow through by sending a polite thank-you email, this will set you above 99% of humans. Just saying.[3]

Maybe now’s a good time to address a classic networking question: what do you call someone you’re meeting for the first time? Sometimes the person will give you the cue (as the poet Danez Smith kindly did for a student of mine, extending a hand and saying, “Hi, I’m Danez”), but sometimes it’s less clear. Talk to trusted advisors about this, since regional and cultural manners can vary. I advise students to err on the side of formality – an honorific plus last name – in any professional or academic situation, particular for someone older than you or professionally senior to you (“Ms. Ramirez,” “Dr. Gupta,” “Professor Lee,” “Dean Craft” and “President Ward.”) No matter how innocent, a 20-year-old student addressing a 50-year-old professional by her first name, automatically, as if they were social peers, is just going to grate on some people – with good reason. [4] As you see in my sample agent letter (below), I still default to a formal salutation when reaching out to a stranger. My students call me “Dr. Weldon” while they’re still my students, and it’s a nice social milestone for all of us when, after graduation, I can warmly invite them to call me “Amy.” If the person’s pronouns or honorifics aren’t clear and they haven’t provided you a cue after you’ve talked a bit, I do think it’s okay to ask, “how would you prefer to be addressed?” Overall, the message you’ll send is a good one – I’m showing respect for you and for our social context.

Alongside in-person networking, build awareness: look at the landscape you want to enter and join the conversations of people in that field. A common question on a literary press’s internship application is “What are the last three books you read?” This really means, “Do you read books like ours?” The young-adult fantasy trilogy you binged over Christmas break (hey, no shame) won’t help you at a press that doesn’t publish YA or fantasy. Get and read their books now (interlibrary loan can help.) Browse what the staff members like to read (some websites will have fun little bios, like bookstores have “staff recommendations”) and investigate some of those titles, too.

This is where students protest, “But I don’t have time!” Classes, jobs, activities, family caregiving – I get it. But out of (tough) love, I have to share some good advice I got in graduate school, when I was overcommitted and unfocused: don’t let the important (long-term) be sacrificed to the urgent (short-term). If you really want to finish your novel, if you really want to be competitive for an internship at a literary press, you may have to re-evaluate how you’re spending your time now. Taking a hard look at extracurriculars and media consumption (especially social media) can help. A year from now, what will you wish you had done now?

- Read and tell the story – for yourself and others.

Curiosity gets you interested in other people, just as if they were your characters. As smartphones and Zoom proliferate, students confess to feeling socially awkward when talking face-to-face. But you can use the questioning skill you have as a writer to build a conversation: what happens next? Why did this person do that? A question opens a door for your interlocutor to tell you more, and then for you to identify a note within it: “Sounds like your company’s growing, and there are good opportunities for…” “Sounds like you have a lot of new ideas for….” As a writer, you know how to do this: read (or listen), detect a through-line, and ask more.

Consider what capacities, experiences, and secret superpowers you may already have. For instance, video game design, arts/nonprofit management, fundraising, university development, and marketing all involve storytelling and close reading. So do patient care and diagnosis in medical fields (which involve more intuition and creativity than non-physicans ever see, as Reed Johnson, MD says below.) Jennifer Acker, novelist and founding editor of The Common, advised my students, “You may think you want to work at a literary magazine, and that’s great. But there are other possibilities than editorial ones. Marketing, web design, social media, fundraising – all these things are also part of your work.” [5]

To start thinking about your secret superpowers, think of your own resume like a draft of a story in progress: what is it really about? What’s its through-line or major note? Once, a sophomore student named Susie came to my office, plopped down in my battered armchair, and confessed, “I have no idea what I want to do with my life – can you help?” So we started putting pieces together. Susie was an English major who sang in the school’s prestigious choir and spent weekends volunteering for a rape crisis hotline. A common throughline, therefore, was amplifying women’s voices. Once Susie could see that her own life and interests did have a story, she was able to focus on what she really cared about without getting overinvolved on campus. She also felt a sense of relief and focus about where she was going that helped her identify a new area of interest: counseling and social work. (Careers grow out of skills and interests, not precisely matching majors – you know that, right? Good.)

Your storytelling experience can boost your professional life in lots of ways. Say that an employer looks at your transcript and says, “I see you studied abroad for a semester! Tell me about it.” Most people might rattle off tourist checkpoints. Instead, think, “What is the question I’m really being asked?” (Hint: it’s probably “How will that experience help you contribute to this organization?”) And craft a (true) story in response. Share a few points on what you got better at (curiosity, resilience, understanding cultural difference and historical perspective in non-superficial ways), and then a specific anecdote to illustrate that. Say that you spend your summers working road construction. This can say a lot about your ability to work hard on a team with a variety of people to accomplish a real and important goal – and I’m guessing you’ve also got great characters and details from that experience. (“Manual” jobs are nothing to be ashamed of – in fact, they give you stories and skills that other people really respect.) Say that you’re a single parent pursuing your college degree and your dream of writing a novel. What does this say about your ability to balance multiple long-term goals and daily stresses and inconveniences – but also joys, which you know in a way many people don’t? Your experiences as a writer and a person make you capable of building fictional worlds and real organizations like the one you’re interviewing for.

- Identify what helps you or holds you back – including online habits.

Given the ambient shittiness of the twenty-first century, controlling what you can is a matter of survival, emotionally and professionally. And by now, there’s no denying it: social media, YouTube, and their ilk are adding to that shittiness, in every way. This is true even if you aren’t a disinformed Capital insurrectionist. Sure, social media does help witnesses and activists get the word out. It can help writers find community. But it’s also terrible for physical, social, mental, and economic health. Even so, many students rely on it as their portal to the world, often to the exclusion of legitimate news sources and face-to-face relationships. This is, and will be, a real professional problem: as your range of media consumption and social interaction narrows, your range of motion in the world beyond your peer group narrows too.[6] So: how should you manage or control your habits, especially electronic ones?

Pause while I dodge thrown tomatoes from people under 30 complaining (rightly) about the economic and ecological dystopia we’re foisting on them, the refuge social media offers them (well, kind of), and the OK-Boomer tiresomeness of people like me. (Will anybody even know what “OK, boomer” means by the time this book comes out?) My students point out that quitting all social media (as I’ve done) will harm their professional opportunities in ways it won’t for me. Maybe so. But we can’t stay hooked, uncritically, on this thing that’s killing us. And, yes, social-media-made myopia and disinformation (see the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection, COVID-19 vaccine denial, and climate emergency) are literally killing us. The Internet has already killed a lot of opportunities, for artists and others, in our Amazon-dominated world.[7] Since, as Jaron Lanier says, “attention is the new oil,”[8] whatever draws attention on the Internet – particularly anger, outrage, and fear – makes its creators money, whether or not it’s good for humans, nonhumans, and our world. As I’ve taught college since 1998, I’ve seen that as students get more screen-focused, they often become less, not more, aware of the world offscreen. Sometimes people don’t know where to look for information. But sometimes they just aren’t looking.

At first, this just seems naïve. But naivete becomes embarrassing when a college senior can’t join a conversation during a dinner with potential employers (or when those employers find their keg-party pictures on Facebook). It’s ironic when a creative writing student “active on Twitter” doesn’t know about #PublishingPaidMe. And it’s tragic when a creative writing student seeking a literary internship doesn’t recognize Booker Prize or National Book Award shortlist authors or the presses that publish them. Yet just about every student in my classroom has a smartphone. And every student in my classroom is hoping that being there will help them navigate the world to come. So, ask yourself: how am I actually spending my precious attention, and is it getting me the results I want?

Now that the tough-love interlude is over (thanks for listening – y’all know it’s because I care about your success, right?), let’s identify professional resources around you, starting with your campus and community.

Level One: Your Information Ecosystem

Get savvy about the professional world you want to enter by entering the ecosystem of reputable information around it and voting with your attention and your dollars (however limited) to support its health. For writing students, this might look like this:

- Get at least a rough draft of your resume and a job letter in your computer, to be added to and updated as needed. Your college’s Career Center can help you with this and more.

- Listen to National Public Radio and read a newspaper like the New York Times (including general news coverage and book reviews; they also have great free podcasts.) Subscribe or donate if you can, to support reputable news and the people who gather it. Your school may also provide free online access through its library.

- Read good newsletters like Literary Hub (lithub.com) and Publishers Lunch; individual presses and magazines also have their own newsletters and podcasts. Follow the links to learn more about titles or authors that interest you. Poets and Writers Magazine (pw.org) is a good source of writerly news, interviews, submission opportunities, and professional guidance. So is “Don’t Write Alone” at Catapult.co. And, yes, scanning Twitter (which even I sometimes do) can help you listen in on conversations without having to sign up.

- Use your library – it’s free! In addition to print and online access to books and films, your library will also have a Current Periodicals section, where magazines and newspapers wait eagerly on open, browsable shelves. (Subscribing to The New Yorker as a college sophomore changed my life; my footnotes here are full of such magazine ideas.) If they don’t have a book, they can usually get it for you via interlibrary loan. And librarians love to help.

- Vote with your dollars for the writerly ecosystem that supports us. Buy books from a local independent store or an online source that supports local independents, like bookshop.org. (Aside from obvious benefit to local economies, sales figures – including pre-orders – from these stores help writers get their next book contracts.) I subscribe to an e-book and audiobook service called Scribd that costs me about $10 a month – a great deal. If I want to buy a cheap used book or splurge on a first edition, I can often find it at abebooks.com. And even if you can’t buy books, keep using libraries – what libraries buy and subscribe to also matters.

Level Two: Writing-Related Jobs and Publication Credits on Campus

Here are some places to look on campus for writing-related opportunities:

- Marketing, publication, athletic communication, development/alumni-communications, and/or departmental offices. One English Department student worker started a one-page weekly newsletter for our students and faculty.

- Newspapers or literary magazines. (As seen in Shannon Baker’s Ch. 1 Student Craft Studio, there are also national and regional undergraduate literary magazines, including those from honor societies like Sigma Tau Delta). You can write for these, join their staffs, or both.

- Academic support centers, like our college’s Writing Center – a great foundation for an editing career.

- Libraries and/or archival collections (library and information science, by the way, is a great field for writers!)

- Alumni connections: colleges have lots of ways to make these happen. Which alumni of your school are working in a field you want to join? (Hint: say please and thank you, early and often.)

- Named scholarships: Fulbright, Marshall, Rhodes. These offer students focused, prestigious academic honors and experiences that can become powerful parts of your professional story.

- Campus career center: from resumes to internship and employment connections, a career center can help everyone, no matter your stage of the process.

- Campus events: as the co-director of the Luther College Writers Festival, I recruit students as volunteers, which can include the opportunity to write website and printed materials, introduce writers at the mike, guide them around campus, and talk with them.

- Conversations, advising, and research work with professors. Especially at small liberal arts colleges, that’s literally why we’re here. Following the “Castles in the Air” exercise above, I went on walks and made Zoom calls with students to talk with them about next steps and share their feelings. This kind of guidance is also part of a professor’s job. If professors feel able to vouch for you, they may also connect you with other opportunities or professionals in their fields, or with research assistantships for their own work (see Annika Dome in “Student Career Studio,” below). But this process starts with you, not the professor. Make that appointment, have that conversation, and, again, say please and thank you.

Level Three: The Wider Writing World

Here are some ways to move into the writing world beyond your campus:

- Seek publication opportunities (no matter how small) in magazines and newspapers. Book reviews are a classic place to start; so are community newspapers (where Ian Wreisner of Ch. 4’s Student Craft Studio got a summer job). For creative work, journals and presses will have submission guidelines on their websites.

- Start a workshop group with people from your writing class after your class is over.

- Attend readings and events at local bookstores.

- Investigate writing classes at community arts centers like the Loft in Minneapolis.

- Internships (which professors and career centers can help you with) can be found in many places, including on the websites of presses and journals you admire. These may be in-person or remote opportunities, paid or unpaid, and you need not always be a student to take advantage of them. For example, as I write, the literary journal The Common has just sent out a call for manuscript readers – people willing to spend 3-5 hours per week reading and evaluating submissions, who are important parts of literary journals’ staffs.

- Writers’ festivals and gatherings (like my own Luther College Writers Festival) are great ways to mingle with other writers, learn new things, and get inspired over a weekend or so. Most of these are focused on readings and panel discussions rather than workshops (see below), but they’re fun and relatively inexpensive.

- Writers’ conferences – like Tin House Summer Writers Workshop (the one I described in Ch. 7), Sewanee Writers Conference, and Bread Loaf Writers Conference – are fabulous “summer camps for writers” that offer you focused workshop experience and professional advice. They do have an admission process, and they do require an investment of time and money. But based on my own experience with all three of those listed above, I can say the return on that investment is And many offer active outreach to, and scholarships for, students. More of these are listed in Poets and Writers Magazine.

- Writers’ residencies – which offer housing and financial support for writers – are another opportunity to apply for. Writer R.O. Kwon (below) says, “I also always point people to the backs of books in the acknowledgments — especially in people’s first or second books — in which most people will list everyone who’s ever given them money or a space to write. That helps a lot.”

- The Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) has an annual conference that takes place in a large city over four to five days and draws crowds of around 15,000 people. Yep, it’s huge, and it can be expensive, by the time you factor in lodging, transportation, food, and registration. But depending on your goals and strategies, AWP may be worth a try. It’s built around readings and panel discussions on every topic you can imagine (the printed program is the size of a small town’s telephone book!) and a book fair – a cavernous space full of display tables at which the staff of presses and magazines sell their wares and talk with writers. As you can imagine, the networking opportunities are considerable (remember the young lady at the Graywolf table, above?) As an organization, AWP offers other resources and workshops for writers; see their website at awpwriter.org for updates.

- Lots of resources on the Internet and Twitter offer honesty about different aspects of writing, publishing, and trying to support yourself financially while writing and trying to be published. A full-time job and a writing life are not necessarily incompatible, as Richard Mirabella describes in his essay “On Writing (With A Day Job.)”[9] Just to take one example: in July 2020, New York Magazine’s “The Cut” asked six women with recent books “how they make writing work financially.”[10] Here are some samples:

- Samantha Irby: “Any time I talk to anyone and they’re like, “I want to be a writer,” I’m like, “Get a regular job.” Try not to depend on your writing to fund your life because it, uh, won’t.”

- R.O. Kwon: “For most of the time before I sold The Incendiaries, I favored freelance jobs that I could do from home. I very quickly realized that I’m very introverted and it’s hard on me to engage with people every day except with the one person I’m living with. So that is something I often try to tell people, especially students. It can help to figure out what kinds of jobs will leave you more energy at the end or start of the day, whenever it is you can write. And once you figure that out, it helps a great deal.”

- For many years, I’ve been recommending Meg Jay’s book The Defining Decade: Why Your Twenties Matter and How to Make The Most of Them Now (2012; updated 2021) to my students. Of all her good advice, perhaps the best is this: Don’t wait for the “perfect” opportunity to come along while you spin your wheels, inert and anxious – get moving, even if it’s in a new direction, because it could lead to something good.

Student Career Studio: Andrew Chan (UNC-Chapel Hill Class of 2008): Web Editor at The Criterion Collection and Freelance Writer (The New Yorker, 4Columns, and Others)

I first met Andrew Chan at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in 2004, when he was an incoming first-year student and I was finishing my Ph.D in literature. Andrew was the third-ever winner of the Thomas Wolfe Scholarship in creative writing, the application for which includes a “Why I Write” essay like those in Ch. 1. As a selection-committee member, I got to meet Andrew in person: funny, smart, and kind, he also knew more about film, even in those pre-Netflix days, than anyone I’d ever met. At Carolina, Andrew minored in creative writing, including extensive coursework in poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction. Now, he’s Web Editor at The Criterion Collection, which preserves, streams, and educates viewers about world cinema. His writing appears in its newsletters, Lincoln Center’s Film Comment Magazine, and The New Yorker,[11] among others, and he’s writing his first book on ’90s pop culture and R&B. Over email, Andrew and I discussed how studying creative writing can be a springboard into your post-college professional and intellectual lives.

Can you describe your path from Thomas Wolfe Scholar to New York film critic: what were some concrete steps you took to move from one level to another?

I’m not sure how conscious I was of the steps I’ve taken; what I remember most is the uncertainty. At the time that I graduated college, in 2008, the economy was in freefall, and film criticism had already been pronounced dead several times over, at least as a profession that could offer a financially secure life. So I have to admit that the path I took was probably the most cautious one available; I’m sure bolder, more ambitious people have found it easier to get a foothold than I did in my early years in New York.

The key to it all was actually moving to the city, where all the viewing and reviewing opportunities were (and still are). I got an internship at the Museum of Modern Art’s film department in my junior year of college, and I used that as an opportunity to meet some of the film critics I most admired. Then I went to NYU’s cinema studies graduate program and interned for Film Comment, a magazine I revered, for about two years. The world of magazines (what few of them are left!) can seem elite and opaque to anyone who’s young and on the outside, but I was lucky enough to find generous editors who opened the gates to me, and I just began writing, pretty relentlessly. I knew I probably couldn’t ever rely on film criticism to pay the bills, but the more I wrote and the more I published, the more I wanted to keep it going.

At a certain point I had to pare down the writing; I couldn’t sustain that pace, nor was I interested anymore in trying to drum up semi-interesting things to say about movies I cared nothing about. There were years when I wrote no criticism. But having day jobs within New York’s film world—as a marketing manager in the film department at BAM (a performing arts venue in Brooklyn), and as an editor at the Criterion Collection—gave me the financial security that then opened up more mental space. I began to carefully consider what it was I wanted to be writing and the subjects I wanted to tackle. And it was when I started becoming extremely selective about my subject matter (a luxury that I realize most freelance critics and journalists do not have) that I regained my self-confidence and people started paying more attention to my work. There’s no question in my mind that my writing got better.

That’s a short way of conveying the twists and turns of my writing life over the past thirteen years!

What does a typical day look like for you?

As a writer, I’m constantly wrestling with the finite resource that is time. Most of my hours during the workday are taken up with my work as an editor at the Criterion Collection. It can be incredibly intellectually energizing; I’m helping writers figure out how to make their pieces better, and often I feel like I’m figuring it out right alongside them. Having come to the editorial profession as a writer first, I think I have a certain perspective in the job: I am on the writer’s side, and my solutions are rooted in and informed by my own experiences tinkering and laboring over sentences.

It can be hard to cobble together the hours (and the energy) to write when you spend so much time working on other people’s writing. So, much of my writing life is project- and deadline-based: I have freelance work that I do on weekends, and now I have a book project that is churning away in my brain. There’s a lot of journaling and note-taking and trying to capture the ideas and phrases that will make it easier for me to get the job done when I’m lucky to have a solid day or two just for composition.

How do you think studying creative writing helped you build your life and career – tangibly and intangibly?

Like a lot of young writers, I really did not know how to revise. Either I would be so enamored of what I’d done that I couldn’t see alternatives to the words that were on the page, or I was so embarrassed of my failure that I couldn’t see a path to salvation or improvement. Workshops can be grueling when you are so emotionally invested and take your writing so seriously. If the study of creative writing taught me anything, it’s the joy in refining and sometimes radically reenvisioning a piece. It reshaped my ideas about where the pleasures of writing lie: if you can find pleasure in wrestling with what’s on the page, and relinquishing your perfectionism, you will set yourself up for a much happier writing life. The focus becomes less on initial inspiration and more on the process (and the time and the devotion) it takes to create something worthwhile for the reader.

As a gifted critic, what are your thoughts on how criticism relates to other kinds of “creative writing?”

Criticism of all kinds is bound up in the magic of the art that it describes. Great critics have shaped how I experience the art forms that I love—whether or not I actually agree with their positions and assessments. When you don’t grow up around a lot of people who are passionate about the arts, you rely on these writers to share in that experience with you, and to guide you. And of course aesthetic experience is as profound as any other kind of human experience, so in a sense I don’t see any fundamental division between “creative writing” and “criticism”—they are both trying to render, in sentences, what it’s like to be a human being undergoing an experience.

Your career has tracked in really interesting ways with the rise of the digital realm, which is reshaping the way film, writing, and other arts get produced and marketed. Yet you obviously occupy and love the world of old[er]-school art forms too. How might current college students think about the balance of these in their own artistic and professional lives?

Digital publishing has certainly made it easier for writers to get bylines and put together a portfolio, but it has become harder and harder for anyone to make a living off freelance writing. Not to paint too bleak a picture, but the drive for more and more content has created a publishing ecosystem in which content is churned out on the cheap and then, often, forgotten. Most freelance writers I know who write for primarily digital outlets are working from assignment to assignment, with no real certainty that their next pitch will be greenlit. You have to be aware of these realities in order to keep your spirit and curiosity as a writer alive. The obstacles and the challenges often have nothing to do with your skill or talent. I realize this is not what a lot of people want to hear, but I encourage caution: if you love writing, you have to be prepared to do it on your off-hours, often for little pay and little fanfare. Use the opportunities created by the digital landscape’s endless hunger for “content” to stand out: just because outlets are looking for something quick and disposable doesn’t mean you can’t turn the assignment into something timeless.

What advice would you give your student self? And/or students reading this book right now?

I’m not sure how much stock someone should put into my advice because my path has been a bit unorthodox. Looking back on my career, I realize how fortunate I’ve been, and at the risk of sounding disingenuous, I have to say that some of it was unintentional on my part. I’ve always been a risk-averse person—the classic result of second-generation American financial and social insecurity, perhaps—and so I never really allowed myself to take on the identity of “writer” or to pursue my creative dreams with naked ambition.

But that doesn’t mean I didn’t put a lot of time, work, and patience into every piece I’ve published. And because of my lack of a clear path, I opened up myself to covering a pretty wide range of subjects: not just film but also literature, music, and other kinds of culture and art. Even though some of what I’ve shared here might sound a bit discouraging, my final message—both to readers of this book and to myself, because I’m in constant need of hearing it—is that if you’re faithful to your curiosity and your love of the written word, they will take you places you never expected. Open those windows; walk through those doors. Do it for the love of it, not for money or attention. Those things may not arrive on the schedule you have in mind; they are not promised. But if you nurture your relationship to language, if you immerse yourself in the art of the phrase and the line and the sentence, and (even more crucially) if you continue to find pleasure and excitement in the themes and subjects you’re tackling in your work, you will be giving yourself something that money can’t buy: something to live for.

Wow – I love that, and I need to hear it too! Any closing words?

It’s important to create space in your writing life for play, improvisation, and failure. This is something I didn’t understand in my perfectionist, somewhat masochistic early years as a published writer. I would spend hours on single sentences. And I would imagine that there was inherent nobility to that kind of rigor. Sure, there can be… but that approach can also engender what I inelegantly refer to as “writer’s constipation.” You become so afraid of the wrong word, the false sentiment, the poorly constructed sentence that you can’t move, you can’t think. A few years ago I retaught myself how to write longhand, and while it wasn’t any kind of cure-all (nothing is), I found it helped. I could write in a journal and accumulate material more casually, without the pressures of having to deliver perfectly sculpted sentences on a computer screen. When your writing life is dictated by assignments and deadlines, as mine has been for many years, a desire to maintain the appearance of professionalism can take hold, and you forget how to take risks; you lose your relationship to the strangeness of language. I’ve gradually had to find my way back to the possibilities that risk creates, and while I’m still struggling with it, that process has helped me to build in time in my daily life for imperfection.

Other former creative writing students say…

Derek Lin: Founding Editor and Editor-in-Chief, The Starter (Luther College Class of 2020); Former student co-editor at The Oneota Review (Luther’s undergraduate literary journal)

In March 2020, the world changed. The edges of the world suddenly became my bedroom walls and possibility shrunk with it. But in September 2020, I lit a flame and began to nurture a fire. With a global pandemic severely limiting my job search, I found myself sitting around with the skills to write, to edit, to design, and a burning need to create, but no work for those skills. And I wasn’t the only one. Friends all around me were in the same boat. So, I went with something I knew to forge something new. In September, I pitched the idea of launching a literary and art journal to a graphic designer, who was one of my best friends from high school. We could craft something that blended our strengths and simply, craft something. Something that would attract and allow our friends and others a space to share creative work. A space within their reach that would seek to provide emerging creatives professional experience at a launchpad level. A space that would allow all involved to hone their skills, staff and contributors alike. Proof that our studies mean something.

Consider why we learn writing. We learn writing to help us communicate, to record thoughts and pass them to one another visually. Creative writing is a continuation of that concept, with the focus for study on the creative aspect– the aspect of creation. As such, creative writing serves as the foundation for when I design or work on social media posts for The Starter. I’m a user of written words, even in those alternative communication formats. I create stories and journeys, even there. It’s enrichment, it’s meaning. The thing about studying creative writing is that it teaches you ways to focus your creative energy so others may read it. Put together your poems, your short stories. Then keep going.

Reed Johnson, MD: Internist (Luther College Class of 2016)

It continues to amaze me how many writers first trained as physicians. Recently, I learned William Carlos Williams was also a general practice doctor. At the core of being a good physician and being a good writer is the ability to pay attention and notice. Unfortunately, in the age of numbers, it is very easy for physicians to not be as good at noticing the small details on a physical exam. Previously, physicians had to notice the most minute details in ordered to make informed decisions about treatment, but that is no longer the case with all of the imaging and lab results that are now available every day in medicine. But I hope to be able to continue to emphasize learning these observation skills and carry on this time-honored ritual of medicine.

Vocation is something I have been thinking about recently too because in the last month I have been quite busy. This has increased my level of fatigue, which makes it harder to enjoy what I am doing. I have been thinking about it along the lines of passion. When I was in high school and at Luther, I remember feeling pressure to “find my passion.” But I never really felt that any of my interests fully met the intensity threshold to be called a passion. The more time I spend learning medicine, the more I realize that “passion” is something that must be learned and cultivated over time. Part of this realization came to me when I asked a more senior physician if he’d seen any interesting patients recently. He replied by saying, “all your patients are interesting once you know enough.” The more I learn about medicine, the more I realize that it is an art. And I think the “passion” that I was told to find when I was in undergrad actually comes from learning to love the practicing of an art form. To clarify, this is not the same as being good at an art form. It is learning to love the journey inherent to developing and nurturing the art and beauty of what you do. It is not about the destination.

————————————

[1] https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/7178/the-art-of-the-essay-no-3-hilton-als

[2] You can see my review (from Orion’s Summer 2018 issue) on my webpage, amyeweldon.com.

4] Lots of convos in higher ed about this, with general consensus being that for women in general and women of color in particular, using an honorific and last name can be a marker of necessary respect. See https://www.chronicle.com/article/do-you-make-them-call-you-professor/, https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2015/03/11/advice-young-black-woman-academe-about-not-being-called-doctor. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/02/opinion/sunday/they-call-me-doctor-berry.html , https://www.thelily.com/a-white-city-official-refused-to-address-this-black-professor-as-doctor-he-got-fired/

[5] 11/12/20

[6] Sorry, y’all, the data is in. See Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge, “This is Our Chance to Pull Teenagers Out of the Smartphone Trap,” New York Times, July 31, 2021 (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/31/opinion/smartphone-iphone-social-media-isolation.html). Haidt and Twenge quote a college student who wrote to them: “Gen Z are an incredibly isolated group of people. We have shallow friendships and superfluous romantic relationships that are mediated and governed to a large degree by social media. There is hardly a sense of community on campus and it’s not hard to see why. Often I’ll arrive early to a lecture to find a room of 30+ students sitting together in complete silence, absorbed in their smartphones, afraid to speak and be heard by their peers. This leads to further isolation and a weakening of self-identity and confidence, something I know because I’ve experienced it.”

[7] See William Deresiewicz, The Death of the Artist: How Creators are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech (2020)

[8] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/09/23/opinion/data-privacy-jaron-lanier.html

[9] https://catapult.co/dont-write-alone/stories/on-writing-with-a-day-job-how-to-write-working-9-to-5-richard-mirabella

[10] https://www.thecut.com/amp/article/how-writers-make-money.html

[11] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/09/kaveh-akbar-finds-meaning-in-misunderstanding